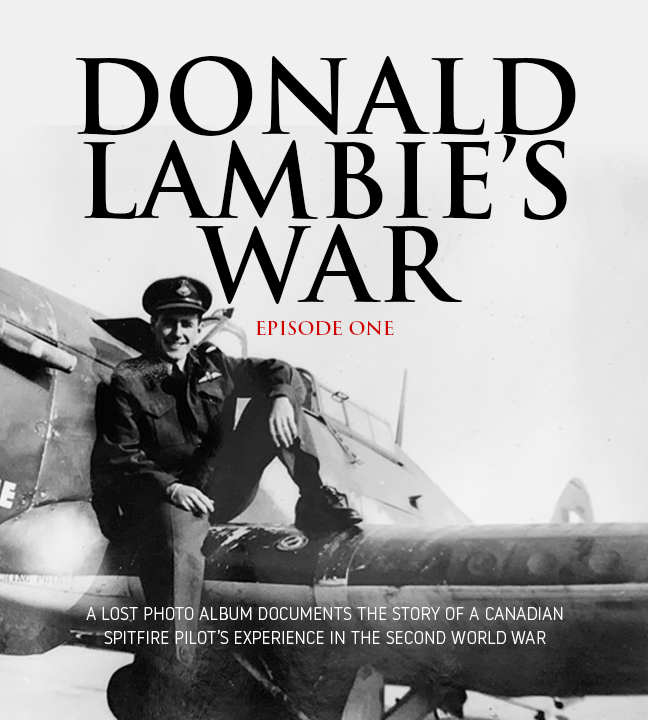

DONALD LAMBIE’S WAR - Episode One

March, 2022

Of all the veterans of the Second World War who I have met and written about over the years, the one I knew the best, loved the most and miss the deepest was a Scotsman named Warrant Officer Harry Hannah, a Spitfire pilot with the legendary 602 City of Glasgow Squadron and a prisoner of war for two years. This story is not about Harry, but he is where I need to start.

Harry died three years ago at the age of 98, elegant, diminutive and dignified until the end. Over the years of our friendship we shared a unique and trustful bond that allowed me to tease out the story of his life and his extraordinary experiences, both uplifting and privative. Harry was a very reserved man — humble, quiet-spoken and not given to putting himself at the centre of a war story. Like many who saw what he saw during the war, Harry was a pacifist. His story was unique in many ways for a Scottish pilot in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve during the Second World War — the way his war started (as an aircraft mechanic). where he learned to fly (Arizona), what happened to him (shot down in his Spitfire) and how he survived (a PoW for two years including a year in solitary confinement).

To remind me now of Harry’s life and our friendship I have a few of his favourite treasures from his war years—his embroidered 612 Squadron crest and necktie, a hand-written memoir that I had coaxed him to write down in the last years of his life and best of all, his bejewelled Caterpillar Club pin and Certificate of Membership signed by Leslie Leroy Irvin himself (founder of the Irvin Airchute Company, the world's first parachute designer and manufacturer).

These cherished mnemonic objects rest in places of honour in my office and library where, as I write this story, I can see them and bring Harry to life again. But for all the clear-as-day echoes of my friend Harry, I have but a single photo of him from the most extraordinary and important five years of his life. And it’s a poor one at that—a low resolution squadron group photo with disruptive labelling ruining what little evocative soul it might have had. I found it on the internet and Harry is in it, but from this image I can tell very little about him—who he was, what he did, or how he lived. I would have loved that insight.

When Harry was shot down in 1943, he lost all of his personal records, log book, and many photographs — packed up I supposed and lost to the bureaucracy of the RAF. After two years in prison, those important documents of his RAF service would never be found. The few images that he did have that survived the war were loaned to a squadron mate to be copied. That was the last he saw of the remaining photos. It was never clear to me whether Harry had taken many photos or saved images of himself and his friends from that period. He simply made it clear that whatever he once had in the way of images was long gone. And that was that. At that time, Harry still had the memories.

The only image of Harry Hannah during the war to come to light is this 602 Squadron group photo taken at RAF Lasham where the squadron was based for most of April 1943, a few months before Harry was shot down. This is the only image of Harry from his wartime service, all his photographs having been lost in the intervening years since the war. Harry sits in a relaxed manner beside his best friend Jimmy Kelly. Kelly would be shot down and killed after D-Day the following year. The loss of Kelly hit Harry hard when he found out about it after returning from prison. Photo: 602SquadronMuseum.org.uk

When it came to telling Harry’s story here on the Vintage Wings story service, I had no photographs to colour his words, to show him with his friends on and off duty. Nothing. While this made the storytelling more challenging for me, it was for another reason that I wished for a few photos of Harry from those days.

As Harry’s memory and sense of belonging began to leak away at the edges in the final years of his life, I could see he was becoming lost with no milestones or signposts to guide his way. As we sat and talked in his basement living room, I saw how the light would come to Harry’s blue eyes when we talked about those days or that airplane he loved so much. I saw how that same light would fade from those same eyes, and how his memory receded back into the darkness whenever a silence came between us. It was as if time was fiddling with an emotional rheostat, powering his memory up, then dimming it down. How I wished for a photo album of Harry’s war that we could sit upon our laps and turn the pages of and talk and laugh about. How I wished for those old, faded sepia-toned photographs that could connect him to his past, that could bring back the light. I longed for something I could bring out from under the coffee table on every visit, ask the same questions and coax the same or even new memories out from where they abided. Story telling begins with listening and I sure loved to listen to Harry Hannah.

So, you might ask, how does Harry’s story relate to Donald Lambie, a Canadian fighter pilot who was just learning to fly when Harry was shot down in France in 1943. Well, it’s about photos.

A treasure found far from home

My friend and colleague Jeff Krete, one of the world’s most respected wildlife carvers, was travelling with his brother and their wives in the first summer of the pandemic and, as they are wont to do on all of their trips, they enjoyed visiting antique shops and garage sales, looking for vintage treasures. Last year, Jeff wrote to me to tell me about a personal photo album his brother had come across in a small antique store on Manitoulin Island, the largest island in the Great Lakes. Here he describes how they came across this extraordinary find in a place far from its creation.

My brother Tim [Krete], his wife Lynne, my wife Marna and I all vacation regularly on Manitoulin Island. As part of our trips there, we like to travel about and collect old treasures. Tim and Lynne are in the business and have a couple of shops selling vintage things — Pretty Vintage and The Toy Society located here in Cambridge [Ontario].

Tim and I grew up in the 60s in a household where our parents collected antiques. They had a fondness for old things. When he was young, Dad had been in the Essex Scottish and Highland Fusiliers of Canada. I recall his stories of training exercises, especially driving tanks at the Meaford Tank Range. Tim and I also grew up in a family which had some veterans and family friends who were veterans. In that environment, I think we came by our interest in old things and militaria honestly. Tim especially, is always digging when we go on our picking trips together. He has a knack for it far greater than me. He also has more luck than I do! Lynne can tell him he has 30 minutes in a whole building and somehow he comes out with the gold! Anyway, in June of 2020 we went to a small antique business Tim found on the island. We all went inside and a couple hours later we came out with our treasures.

I found an old 60s control-line P-39 Airacobra and a few other cool things and Tim had quite a pile. Tim always checks out old photo albums and found a large one it at the bottom of a nondescript pile of books. He purchased it for around $30 and really didn’t know what he had until I started to go through it on the way back. He was driving and I was calling out the type of aircraft. Woohoo… a Harvard! a Hurricane, a Spitfire! The photo album was full of images that generated so many questions. Who were these people in the photos? How did this album end up here… on remote Manitoulin Island?

The leather-bound album that caught the eye of collector Tim Krete in an antique shop on Manitoulin Island. The shop’s owner was from Toronto and spent the winters there looking out for unique antiques and collectibles to sell in his seasonal shop on the island. Photo Jeff Krete

As soon as Tim Krete opened the album he knew he had stumbled on something greater than a “collectible”, but rather a unique window on one man’s experience in the Second World War and an historic record of a sparsely documented period in RCAF fighter operations. Photo Jeff Krete

An initial search of the internet brought to light this studio photograph of Donald Lambie — a handsome, elegant man in his 50s engaged in the insurance business. It was immediately apparent that this was the same man as the 20-year old whose life was so fully depicted in the more than 400 photos in the album. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Tim and I grew up building plastic model airplanes together. I went on to fly RC model planes and take flying lessons, then a brief time in the Canadian Armed Forces (Navy). Dave, you know of my carving and interest in aircraft and connection to VWC. I have and always will be an admitted old aircraft enthusiast. I followed all the warbird restoration stories in Air Classics, Wings, Air Progress and other magazines. I went to every airshow I could, hoping to see WWII aircraft fly.

With great interest, I borrowed the album from Tim, going through the book on a mission to sort out the story in it. Given there was also writing on the back of many of the 400 or more photos, it seemed the story just might reveal itself if I kept at it. I noted the name “Donald Lambie” multiple times and was able to identify that he was the young airman and pilot at the centre of everything. This was his album.

The images covered approximately three years of his life and were in roughly chronological order. I wondered what became of this man. Could he still be alive? I Googled his name looking for him in Toronto and a photo popped up (a black and white one from maybe the 70s).

I searched some more and a Donald Lambie came up with a phone number in Toronto. I called the number and Karen Lambie, Don’s wife answered. You can imagine the random nature of my introduction and story!

She was quite surprised and told me that Don was indeed alive and in one of the Veterans’ wings at Sunnybrook Hospital. He was 99-years old. She knew nothing of the photo album. She was Don’s second wife, having married him in 2004.

My head was spinning with questions for Don but unfortunately COVID-19 would preclude us from meeting him in 2020 and perhaps returning the photos. I tried to send questions through Karen but she could only see him about every other week and needed extensive COVID screening in order to visit him. Given his advanced age we could not overwhelm him with too much.

I worried I would not be able to engage him very much and learn his story. Some months went by and in October of 2021, before we could connect with Don, Karen informed me he had passed away. I wasn’t sure where to go from here so I eventually reached out to you. The rest you know!

Karen indicated that Don had no siblings and no children of his own and how the album was lost is not known. She admitted to having many other photos of Don and that we were welcome to keep the photo album. This presented a problem in that we would need to decide where it should end up. This was not our story but Don Lambie’s and the images are now entrusted to us to do the right thing. We decided donating them to an appropriate museum is the right course of action. But first, we need to sort out Don Lambie’s story.

Related Stories

Click on image

It didn’t take Jeff and I more than a few minutes chatting online to realize that the contents of and the story behind Don Lambie’s album would make an extraordinary tale here on the Vintage Wings news service. With over 12,000 followers, the unique story of Lambie’s Second World War experience would fan out across the globe from Peru to Paris, from Alaska to Australia. It would be an informative and exciting project to work on.

But should we?

Don Lambie died before he even knew that his album was found. What right did we have to even have it in our possession, let alone pore over it with the intent of publishing it. It was, after all, his personal story not ours. What could compel us to tell his story, the story of a man we never met?

Truthfully, it was Jeff and Tim’s original intent to track down the owner of the album and, if he was alive, return it to him. Most antique hunters would break apart the collection and sell individual photographs to Second World War photo collectors. That is where the money is. Keeping it together was never in question for Tim and Jeff. Finding the handsome young pilot in the photos if he was still alive and returning the album to him or his family was the mission.

With the aid of the internet, Jeff managed to track down Lambie who at 99 was residing in an assisted living residence for veterans in Toronto. Unfortunately, COVID-19 protocols meant Jeff could not meet with Lambie in person. Inevitably, after a long and successful life, Don Lambie passed away on November 1st, 2020, a few days after his 99th birthday.

So now what?

If you were looking to find any record on line of Lambie’s wartime or postwar life, you would be hard pressed. Despite coming at him from many directions, all we could find was a short non-emotional obituary which came with a single photo from his 60s. There was also a YouTube link to lovely eulogy at his live-streamed funeral (due to COVID restrictions) given by his friend Bill Webster. Webster begins by describing Donald Walter Lambie as “unforgettable”. It was that word and the lack of other material about this man that convinced us to make sure he indeed was not forgotten.

Men like lambie spent a lifetime keeping their wartime memories hidden in albums or shared over beers in the Legion. Not because they had horrible memories but because only those who were there understood or were worthy of shared tales and laughter. A man like Lambie would never line-shoot or put himself at the centre of a war story. He kept his memories to himself and a few loved ones not because he was broken by them or terrorized by them, but because of honour and the mid-century social norm of modesty. He preferred to let his present day actions speak for him, not ones from half a century past.

Lambie took these photos with a small Kodak Retina or Argus camera which he clearly carried everywhere with him — winter and summer, on leave, on the flight line, on dates, aboard ship and even in the cockpit. It was clearly a passion of his. He did it to have a record of his experiences, to look back upon when it was all over, to share with his family. It’s possible he knew then, but most certainly in his middle age and older, that these three years were the most powerful and formative of his life. He photographed diligently things of interest to him, people important to him and events that changed him. It was an outstanding record, the likes of which we rarely find these days. More than 400 photographs documenting one man’s war service from enlistment to demobilization, carefully curated and lovingly kept… yet somehow lost.

If we had asked Don Lambie while he was alive if we could do a lengthy two-part photo series on his personal war experiences, he might have declined out of modesty and a degree of self-effacement. Men like Lambie, who finally managed to get into the fight in the closing months of the war, thought of themselves as Johnny-come-latelys, having missed the Big Shows like the Battle of Britain, Malta and D-Day. There was a tendency by these heroes to downplay the importance of their role in the war. But now, having saved these photos from the landfill or obscurity in a collectors’ secret stash, I know he would be very and secretly proud of what we have done, though perhaps he might have a long errata for us to deal with. Because of the inevitability of time, Lambie cannot help us tell his story perfectly. There are no living corroborators, but with a decent knowledge of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and the wartime Royal Canadian Air Force, and with a hard won knowledge of where to look for answers, we can do real justice to Lambie’s story.

The following story and the soon-to-be-released Episode Two are tributes to a man Jeff or I have never met, but who somehow has become a friend. His is not the story of some great ace like Willie McKnight or George Beurling. It’s not the stuff of film and books, like The Great Escape or The Dam Busters, but it is unique and worth the telling. He risked his life through more than years of training, then spent just two months at war’s end in actual combat operations to clear the German Army out of Italy. Following VE-Day, he was rewarded with a period of decompression as he and his squadron mates commandeered a staff car and toured the visual wonders of the Italian Dolomites and Austrian Tyrol.

Jeff Krete and Karen Lambie at her home in Etobicoke, Ontario in 2022, a little more than 100 years after the birth of Donald Lambie. Photo: Jeff Krete

The album that once belonged to Donald Walter Lambie contained only photos of his three years in the Royal Canadian Air Force — from enlistment to demobilization. Luckily, Jeff Krete was able to make contact with Lambie’s widow Karen and after several telephone conversations, during which he explained what he had found and what he hoped to do with it, she agreed that they could meet in person. Karen, was able to fill in some gaps in Donald’s story as she remembered it.

It was the second marriage for both Donald and Karen (in 2004), they having met in a grief support group following the deaths of their first spouses. Donald Lambie was grieving for the loss of his first wife Elizabeth (Hurst) who he married late in life in the 70s. Elizabeth was the widow of Sergeant Joseph William Lapp, who was killed in action in the Italian campaign while serving with the 48th Highlanders of Canada on October 3rd, 1943. The Italian campaign would continue for more than a year after Lapp’s death and include a Spitfire pilot by the name of Pilot Officer Donald Lambie.

Karen had never heard of her husband’s lost album but expressed gratitude that Jeff and Tim had made an effort to return it to its rightful owner. She also worried that all of his military memorabilia would be lost after her own passing. They had no shared children who might consider becoming stewards for his photos, decorations and service records. She expressed her relief at finding a group of concerned and interested custodians and gifted the entire collection to the affable and sensitive Krete.

Donald and Karen Lambie on the occasion of their wedding in 2004. With Karen’s help and the gift of his mementos, we are able to tell more of his life story than even she knew. Photo via Karen Lambie

At the end of his first meeting with Karen, Jeff carried with him all of Lambie’s childhood photos, log book, pay book, service documents and decorations. For some unscrupulous memorabilia hunter this would be a motherlode to be broken up and sold off to collectors of such things. It would not fetch crazy money, but enough to make it monetarily worthwhile. For instance, a full set of Second World War campaign decorations like Don’s that can be tied to an officer in the RCAF who was a Spitfire pilot could fetch hundreds if not thousands of dollars. Instead, Karen found in Jeff and Tim two men whose solemn vow was to keep the collection together and to find a museum that would welcome a complete collection that told part of the story of the late war RCAF.

Aviation museums across Canada are well-endowed with materials that tell the story of such legendary events as the Battles of Britain and Atlantic, the Bomber Command campaigns over Germany, D-Day and the British Commonwealth Air Training Program, but little is remembered in the public realm about Advanced Tactical Training for fighter pilots at Camp Borden, Spitfire training in Egypt and flushing the last Nazis out of Italy. With this album, new windows will open on that period of the Canadian Second World War experience.

Karen Lambie also released ALL of Lambie’s childhood and family photos to us, a selection of which follows. These photos help us see his upbringing and the sorts of things that made him tick — family, church, music, scouting, sport and comradeship. It is imperative we know a little about the man before we journey with him from enlistment to victory.

Lambie’s Early Life

Donald Walter Lambie was the son of David Lambie, a ship chandler from Grangemouth, Scotland (near the western end of the Firth of Forth) and Edith Annie Bayes, of Bedfordshire, England. Lambie Sr. arrived in Canada in April of 1921, leaving behind a pregnant Edith who would follow in June after David got settled. He took a job in the shoe department at Eaton’s department store in downtown Montreal. Donald, who was to be their only child, was born that October.

One thing evident in all the photos of David Lambie, Donald’s father, is that he was a well-dressed man — turned out in waistcoats, straw boaters, Panamas, fedoras, silk ties and polished shoes. His sartorial obsession clearly rubbed off on his son as you will see later in this story — both in civilian clothes and in uniform. Even as a toddler and a boy, Donald’s clothes were stylish and clearly curated for him by his parents. Young Donald, being an only child, grew up without hand-me-downs and with his father’s Eaton’s discount was always the epitome of a middle-class boy from the Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhood (referred to as NDG by residents) of Montreal’s west end.

Donald had an education typical of mid-century English-speaking boys in downtown Montreal, with one exception. In 1928, his mother Edith took him back to England to visit her family. She and Donald would stay with her sister Amy L. (Bayes) Harper, the headmistress at Bolnhurst School near Bedford in some of England’s finest horse country. They remained there for two years, with young Lambie attending his “Auntie’s” school. Upon his return to Montreal with his mother in 1930, Donald transferred to the elementary school rooms of The High School of Montreal, the massive English-speaking institution on University Street near the campus of McGill University. He would later move to Iona Public School and then back to The High School of Montreal for his junior matriculation. The High School of Montreal has produced some pretty accomplished graduates over the years, including jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, jeweller Henry Birks, and actor Christopher Plummer. Following high school, Lambie enrolled in the Insurance Institute of Montreal and took a job as an office clerk with the Continental Insurance Company. He was beginning what he hoped would be a life-long career. When it came time to enlist, Lambie was granted a leave of absence from Continental. He returned to the company after his wartime adventures and spent his entire working life in the insurance industry, 16 of those years with Continental.

Most English-speaking Canadians at the outset of the Second World War still had a strong socio-political connection with Great Britain. It was one of the reasons so many young men joined the fight to save Britain. But Lambie’s was deeper than most. His parents were Britons and he was conceived there. When he was a boy of 7 years, he sailed with his mother to England to meet and live with family for two years. While he was there, he was schooled at Bolnhurst School in the hamlet of Bolnhurst, Bedfordshire. The tiny school lay just 1 kilometre from RAF Bedford to the west and RAF Little Straughton to the east. Here we see young Lambie standing third from the left in the back while his Aunt Amy, the school’s headmistress, stands behind. I must admit, there are a few Village of the Damned-like children in this group! Photo: Donald Lambie Colllection

Lambie’s Aunt Amy was headmistress at Bolnhurst for the 32 years before it was closed. Today, Bolnhurst School is a private residence on School Lane in a very rural area.. This will be the first of many modern photos that I have added of locales depicted in Lambie’s album to help add literal colour as well as modern context to his images. The children and Miss Amy were standing in front of the white framed window to the left of the white door in this Streetview screen capture. Photo: Google Streetview

Donald Lambie grew up an only child in a solidly middle-class family in English-speaking Montreal. Many of his comrades from the war grew up in much more hard-scrabble existences, working on the family farm on the prairies or on the family fishing boat. But Lambie grew up well, got involved in the world around him and learned the value of hard work. Counterclockwise from upper left: Lambie as a toddler in the ambiguous clothing favoured by parents in the day; 11 year-old Lambie in 1933 with his father David Lambie down to the docks of Montreal Port for a tour of the visiting Royal Navy sloop HMS Scarbourough, a gunboat of the Royal Navy launched in 1930. She served in the Second World War, especially as a convoy escort in the North Atlantic. Lambie’s father worked in the shoe department at Eaton’s department store as evidenced by high quality wingtips worn by his son; then a photo of a young Lambie having a little fun turning a few garden implements into a chariot of some kind. Lastly, a photo of 8-year old Lambie in 1930 with his German Shepherd dog on Sandy Beach in Hudson, Quebec. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Research into any photo can be an obsession, a rabbit hole from which there is only one exit. The photo of young Lambie and his German Shepherd dog from the previous photo collage had a single word caption on the back — Hudson. For a while we thought that might be the name of the dog, but I got to thinking maybe it was for the small town of Hudson, Quebec on the shores of the Ottawa River as it feeds Lac des Deux Montagnes west of Montreal, a favourite summer spot for English-speaking Montrealers for a century. Google Earth revealed only a single sand beach in the immediate area of the town — a 100 metre long patch of silicon dioxide known appropriately as “Sandy Beach”. I placed the photo of Lambie and his dog into an image I found on the web — a perfect match! “Who cares?” you might say, and you’d have a point, but I find searching for these places and finding the coloured modern equivalent photos to be a way to connect with the life of Donald Lambie and to literally bring colour and a better understanding of his own experiences. Black and white photos have a way of distancing you from the realities of the days and place where they were shot.

Perhaps this is off topic, but this is the Royal Navy sloop Scarborough, the ship Lambie and his father went to visit at Montreal Port in 1933 as seen in the previous photo collage. I always find adding these asides into the image mix helps to colour Lambie’s story. Well, at least I find it interesting.

On another family outing, this time to St. Jovite, Quebec (near Mont Tremblant) Lambie’s visiting Aunt Amy grabs a shot of the family—mother Edith Annie (Bayes) Lambie, Donald Walter Dambie and father David Lambie. One notes the more formal dress worn on outdoor adventures in the 1930s. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Music was always an important part of the young Lambie’s life and circle of friends. He was a member of the youth choir at St. Matthew’s Anglican church in Montreal — seen at left in the bottom photo of the mixed church choir in surplice and cassocks; and fourth from right in the young mens choir performing on stage. Like Scouting, singing in the church choir was one of Lambie’s passions. After he moved to Etobicoke, a suburb of Montreal, after the war he sang in the All Saints’ Kingsway Anglican Church for 16 years. .Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The choir in the previous photo was standing beneath of the three stained-glass transept windows on the south side of St. Mathews Anglican church. Man, I love to go back in time like this! Photo: Google Streetview

Lambie loved the great outdoors and devoted many years of his life to the scouting movement in Canada. In the top photo, Lambie (middle) enjoys a bright sunny day of skiing in March of 1941 with some younger scouting friends [looks a lot like Grey Rocks near Tremblant]. Bottom: Lambie (second from left) and some friends stand for a full-dress scouting group shot at Camp Tamaracouta in the Laurentian Mountains north of Montreal. It was the summer of 1941, Lambie’s first year as commanding Officer of “Ruperts House” (his particular lodge?). Camp Tamaracouta is about an hour northwest of Montreal near the small town of Mille-Isles. The camp has been welcoming scouts for more than a century. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

All the photos of Lambie’s early life are not from the album. They were provided to us by Karen Lambie. What follows however, are largely all from the lost photo album save for a number we have added to flesh out detail and colour to the narrative. It is clear that Lambie had spent many hours assembling the album covering the three and a half years of his war experience and nothing else. It was clearly important to him.

We will never know the story behind the loss of Lambie’s album. It must have been a cherished if only occasionally viewed artifact. Albums often get lost when families change. I won’t get into speculation about the album’s travels since the last time Donald Lambie laid eyes on it. One thing I am sure of however is that he was not the one who let it go to an antique store. It meant too much to him.

As mentioned before, there are several hundred photos in the album and we cannot publish them all. We have selected images from across his experiences, kept them in approximate chronological order and then researched anything we could find about the people, places and periods captured by him and anyone he may have handed his camera to. There exists so much material that we are making this a two-part series. This “episode” deals with his life from enlistment to shipping overseas and involves every part of the BCATP experience — War Emergency Training Plan, Manning Depot, Guard duty, Elementary Flying Training, Service Flying Training, Operational Flying Training, Advanced Tactical Training and Embarkation. It’s rare to come across something so complete.

The second “episode” will deal with his arrival in England, Spitfire Operational Flying Training in Egypt, various leaves, Refresher Flying in Italy, combat flying and squadron life with 417 Squadron, post VE-Day sightseeing and the journey home.

Jeff and I have spent hundreds of hours on this project — scanning and repairing photos, rabbit hole diving, sharing insights, bouncing ideas off each other and working to tell Lambie’s story to the best of our abilities. It has been a great joy and a meaningful endeavour for the both of us.

Don… we never met, but you are like a friend to us. Long may you remain “unforgettable”.

Photos from the Album

Enlistment, August 22nd, 1942

In late August of 1942, 21-year old Donald Walter Lambie, office clerk in the Montreal-based Continental Insurance Company and senior scouting master, went downtown to No. 13 Recruitment Centre in Montreal and signed on the dotted line. Being the only son of English and Scottish parents, he likely was inspired to enlist by stories of the pilots of the Battles of Britain and Malta and other legendary aerial campaigns to save the old country.

His attestation papers would indicate he had attended school on England, Iona Public School, the High School of Montreal and later the Insurance Institute of Montreal. It stated that he was given a leave of absence from the company to enlist and while he was awaiting acceptance, he was taking a troop of Boy Scouts to camp for the summer months. Clearly, Scouting was an important facet of his life. Under Item No. 28 on the form: Other information that many have bearing on this application, the recruiting officer wrote “10 years in the Boy Scouts, last 3 as Scout Leader; Plenty of company experience.” He was in good health save for a bout of pneumonia in 1939 and bronchitis in 1941. He was 5 feet 10 inches tall, but weighed a mere 154 lbs and had a chest of just 33.5 inches. Perhaps a sign of the times, the RCAF wanted to know the colour of his complexion, which was “Dark”. He had hazel eyes (oddly poetic for the military).

In summation, the medical officer who conducted his exam wrote “Good physical condition. Mentally very keen, alert and cooperative.” He was listed as A-1-B (Fit for full flying duties) and A-3-B (Fit for combatant flying duties).

Left: A photo of Lambie in full Scouting attire taken in September of 1942, the month after his initial enlistment. Right: The year before he enlisted, Lambie was already involving himself in the war effort leading a troop of scouts in a Victory Loan Parade in downtown Montreal. No doubt, he was ahead of the game in maintaining his uniform, polishing brass and marching. Photos: Donald Lambie Collection

War Emergency Training Plan (WETP)

University of Montreal, October 8 - December 8, 1942

Some recruits who had plenty of promise upon enlistment may have been long out of high school or college and rusty in some basic mathematical or scientific skills. Others, like French-speaking Canadians or foreign recruits, might need to brush-up on their English in order to navigate the largely English British Commonwealth Air Training Program. Before Lambie could join the proper air force and put on the uniform, he would have to take two months of refresher courses at University of Montreal.

According to Anne Millar, a PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa’s Department of History in her thesis entitled Wartime Training at Canadian Universities during the Second World War,

…from 1941 to 1945, pre-aircrew training was part of the RCAF’s recruiting strategy. As early as 1941, RCAF officials were reporting they would not only need to “undertake the complete training” of all air force trades personnel but would also have to provide academic training to increase the educational standards of a “large part of our aircrew.” Officials recognized the high educational standard required for aircrew training—junior matriculation standing—was eliminating potential recruits who might otherwise make strong candidates. Thus, in November 1941, the first comprehensive pre-aircrew training program was inaugurated under the War Emergency Training Programme (WETP). The Department of Labour, in collaboration with various provincial governments, made special arrangements to provide a pre-enlistment “educational refresher” course in mathematics, physics, English, and other subjects requested by the RCAF for potential aircrew recruits lacking the necessary education. Under the scheme, suitable candidates selected by RCAF recruiting centres signed an agreement to enlist in the RCAF as aircrew on completion of the course and in turn, the RCAF agreed to accept as aircrew those who successfully completed their educational training. The Department of Labour provided all books, classroom equipment, and instructional staff and paid trainees a subsistence allowance of $10 per week while they were in attendance. The RCAF compiled the syllabus, set the final examinations, and used inspecting officers to supervise training. Pre-aircrew training greatly reduced the percentage of failures at Initial Training Schools (ITS) where aircrew recruits took a variety of lectures on theory and navigation in preparation for flight instruction. This success prompted the RCAF to extend academic training to all types of potential aircrew recruits. The RCAF developed a new syllabus comprised of preparatory courses in mathematics, science, and English for pilots, observers, wireless air gunners, and air gunners prior to their entering aircrew training service schools. To accommodate the expansion of the program, the RCAF collaborated with university authorities to substitute radio training with pre-aircrew training and established University Pre-Aircrew Detachments, later known as the Pre-Aircrew Education Detachments (PAED), on university campuses across the country.

One of the earliest photos in the album. Donald Lambie (second from right) poses with his friends in their civilian clothes next to a 1932 Chevrolet Cabriolet roadster at the University of Montreal in October of 1942 — perhaps taken at nearby Mount Royal. The men (L-R: Chuck DePoe, Reg Chapman, Bob Gray, Lambie and Doug Howard) were attending a “refresher course” according to the handwritten caption on the album page. Following enlistment, in order to continue with real prospects for flight or aircrew training, they were required to refresh their math skills, other academics and their study habits. Once the WETP courses were employed, there were fewer failures in Initial Training School. A visit to the Canadian Virtual War Memorial reveals that Doug Howard was killed on operations with 166 Squadron, RAF in December of 1944 while flying as a navigator on a Lancaster. As for the other three men in this photo, I could find nothing on the interwebs to help me tell their stories except that Gray earned his wings with Lambie at st. Hubert. The man on the far left, Chuck DePoe, bares a strong family resemblance to famed Canadian broadcaster Norman DePoe, an American and Oregonian by birth. Many DePoe family histories found on the internet lead to the Pacific Northwest and Oregon. They were of Native American heritage. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Douglas Studholme Howard of Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, the man on the right in the previous photo was killed on operations with 166 Squadron, RAF on the night of 4/5 December, 1944. These photos are not from Lambie’s collection and you might ask why tell his story. Well, he was Lambie’s friend and everyone’s story needs telling. Flying Officer Howard was the navigator on a largely Canadian crew of seven that was lost when their Lancaster crashed returning from a night operation. Howard’s Lancaster (RAF LM176, Squadron Code AS-X) took off at 4:25 PM local time at RAF Elsham Wolds to bomb the German industrial city of Karlsruhe with a load of twelve 1,000 lb. bombs. It was one of two 166 Squadron Lancasters lost on that raid out of 24 participating bombers. Howard’s crew almost made it home, crashing seven hours into the flight near the village of Kirmington, Lincolnshire just 6 kilometres from base. They were in the process of approaching to land when their Lancaster, piloted by Canadian Roy Stanley Hanna stalled and crashed in Brocklesby Park. Photos via The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

No. 5 Manning Depot, Lachine Quebec

December, 12, 1942 to January 21, 1943

The first rung of the ladder to becoming a fighter pilot was Manning Depot, where raw recruits, fresh from college, high school, or the factory floor came to learn how to leave their civilian lives behind. Here they got their haircuts, their issue uniforms and learned to live without privacy, home-cooked meals or peace and quiet. Lambie, being from Montreal, was posted to No. 5 Manning Depot adjacent to RCAF Station Lachine near the shores of the St. Lawrence just a few miles to the east of his home in an area called Dorval.

According to historian Bruce Forsyth, No. 5 Manning Depot:

Opened on 1 December 1941 as No. 5 “M” Depot. The purpose of the manning depot was to introduce recruits into life in the RCAF, with lessons of drill, care of uniform, small arms training and physical training. The Depot was a large RCAF establishment, with around 40 buildings, including administration, messes, quarters, recreation, medical, lecture huts, a central heating plant, and two drill halls. As manning needs declined in 1943, the Depot transitioned into No 1 Embarkation Depot, or “Y” Depot, previously located at RCAF Station Debert. This was a temporary stop-over station for personnel rotating overseas.

Today, the site is home to Montréal–Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport.

Young 21-year old Aircraftman Second Class Donald Walter Lambie stands proudly in his new uniform and great coat near his home in Montreal in the winter of 1942/43 . The date is possibly immediately after Manning Depot or perhaps after he returned from guard duty at Camp Borden on his way to Initial Training School (ITS) in Victoriaville, Quebec. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A photo of Aircraftman 2nd Class Lambie with a young woman named Tess, one of many pretty young ladies recorded in his company. He had no relatives in Montreal save his immediate family, so this is likely his girlfriend. Given the snow and his AC2 rank, it is likely that this is after Manning Depot, and just before he leaves for guard duty at Camp Borden. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Guard Duty at No. 1 SFTS Camp Borden

January 22 to April 3, 1943

When Lambie first considered enlisting, it was not with the RCAF, but rather Montreal’s storied Royal Highland Regiment (the Black Watch) along with his best friend Teddy. He changed his mind and enlisted in the RCAF instead. His friend Teddy did not survive the war.

As was quite typical of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan during wartime, that newly recruited young airmen, having been processed through Manning Depot, were sent to do monotonous and simple tasks to keep them busy until a spot opened up on an Initial Training Course (ITC) or just to get them used to being an airman. By this stage in their training, recruits could march, salute, recognize ranks, polish brass and leather and keep their uniforms in top shape. They had been taught the fundamental rules that governed their time in the RCAF. One of the most common of these otiose tasks was “Guard” or “Tarmac” Duty — guarding the gates to RCAF stations and other RCAF property such as downed aircraft and broken down equipment. Judging by a number of photographs in Lambie’s album, he was sent from Manning Depot to RCAF Station Camp Borden, one of the oldest stations in the RCAF archipelago, in January of 1943 for two and half months of guard duty and whatever tedious tasks needed doing. He was lucky—some airmen were sent to factories to count nuts and bolts.

What’s special bout the photos from this period is their rarity. We hardly ever see photos from this period in a recruit’s life as they were still dazed and confused by by the shock military life and lacking in the confidence to stop and take it all in. Lambie appears not to have been any of these things. In fact, the photos reveal a man having the time of his life.

During the Second World War, the army facility at Camp Borden and RCAF Station Borden, the historic birthplace of the RCAF, became the most important training facility in Canada, housing both army training and flight training, the latter under the BCATP's No. 1 Service Flying Training School. Lambie would return to Camp Borden a year later as a Hawker Hurricane fighter pilot, there to learn how to work with the army to provide tactical air support for armoured units in a theatre of war.

A wartime aerial photograph of RCAF Station Camp Borden looking towards the east and showing the long line of First World War-vintage hangars along the flight line. Today, while the runways are no longer in use and gone to seed, the line of hangars remains, though not in original condition. Overhead photo via FlightOntario

On January 29th, 1943 a North American Yale based at Camp Borden’s No. 1 Service Flying Training School was forced down on a snowy frozen farm field near Milton— west of Toronto, Ontario while on a cross-country flight. On landing, the Yale, RCAF Serial No. 3416, flipped onto its back and suffered Category B damage. As was the custom in the RCAF in those days, two newly-recruited Aircraftmen Second Class (AC-2) awaiting an Initial Training School assignment were dispatched from Borden to stand guard over the wreck to prevent theft, accident or vandalism until a recovery crew and equipment could be mustered. In the case of Yale 3416, AC-2 Don Lambie and a friend was handed a rifle and driven to the site of the crash, there to protect the King’s Yale. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Aircraftman Don Lambie, rifle at the ready, stands on guard beside the forlorn Yale. A folding chair was provided to Lambie to relieve the strain of standing throughout the night in temperatures that hovered around the freezing point on the night of January 29-30—a relatively benign winter’s night for Canada. According to the Operations Record Book for No 1 SFTS at Borden, Yale 3416, piloted by LAC B. J. Hart “turned over while landing near Milton, Ontario at 1700 hours.” “Landing near Milton” must be a euphemism for a forced landing, since there was no airfield at Milton and if Hart was landing there, they would not have used the term “near”. In fact, Hart had become lost on a cross-country flight and with daylight soon to fail, made a precautionary landing, but “turned over”. Though he landed at 1700 hours, sunset that year on the 29th of January was at 1824, so the light was good and the shadows long. Given the prevailing winds in that region, he likely made a landing into the glare of a setting sun, which, any Canadian will tell you, is particularly bad when the ground is covered in reflective snow. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Mechanics from Borden assess the work to get the damaged Harvard onto its wheels and disassembled for the transit to a maintenance depot. The airframe (3416) was assessed as having suffered Category B damage which meant that: "The aircraft must be shipped, not flown under its own power, to a contractor or depot-level facility for repair." It’s pretty clear that even if the Harvard was flyable, it could never have taken off from a snow-covered farm field. We are lucky that Lambie brought his camera with him everywhere so that we can see the kind of assignment new recruits were often given. It’s rare to have that glimpse into an airman’s life. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Don Lambie, this time wearing a great coat, sits on the hub of the Yale’s propeller warming his face in the winter sun while mechanics from Camp Borden assess the damage and come up with a plan. When researching these stories, I find many interesting and telling details in Operations Record Books. The day before Hart’s botched landing (the 28th), a pilot taxied his Harvard into a fuel truck. On the same day as Hart’s accident two Harvards collided while practicing formation flying — with no injuries. Two days later, a Borden-based Harvard turned over at Edenvale, one of two relief fields for No. 1 SFTS. Bad weather put a stop to flying until the 4th of February when a Harvard, a Yale and an Anson all ended up on their noses within 90 minutes of each other at Borden. The pace of training never stopped despite accident rates that would shut down the modern RCAF. There was a war on and schools like No. 1 SFTS understood this was the price of a rapid RCAF build-up. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Taken the same day as the previous photo, Lambie snaps a photo of a young woman sitting on the same propeller hub. It’s doubtful that he knew a young woman in the town of Milton hundreds of mile from his Montreal home, so likely this was a local farm woman or a citizen of the town, drawn by curiosity to check out the downed aircraft. It was a different time when townsfolk could come out to these crash sites and befriend the crews salvaging it. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The Farmer’s Daughter. It didn’t take the handsome young airman long to meet and become friendly with the locals. It’s hard to believe that Lambie knew this woman from the Milton area, and it also hard to believe he could make a friend so fast that he and his fellow airman could start cavorting with such joy in a snowdrift. Other photos on the page indicate that Lambie was staying at this young woman’s farm near the accident site. So, I consider it likely that Lambie and the other guard shown here were billeted at the farm house during the recovery of the Harvard in the nearby field. In the background, the young woman’s little brother “Dave” peeks out. The other photos in the sequence show Lambie not only getting to know the family of this woman, but also helping them out on the farm. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

While Lambie was on guard duty, he helped out at the farm where he was billeted. Here, he drives a horse-drawn milk sleigh with the day’s milk output. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie (left) and his buddy help clear a heavy snowfall from the farm roadway, as young Dave watches. While these photos have no airplanes or air bases in them, these experiences are just as much a part of the Donald Lambie story as anything he experienced later in his war. We are particularly grateful for these insights. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A great shot of ground crew changing the port wheel assembly on Avro Anson 7231. Note the cold weather baffles in the engine nacelles. This particular Anson Mk II was assigned to No. 1 Bombing & Gunnery School at Jarvis, Ontario from December 1, 1942 until a year later when it went into storage. For that reason, I will place this photo in this section on Lambie’s time doing Guard Duty at Camp Borden. His other winter training was a year later, when this aircraft was in storage. I think that possibly Lambie took this photo at Camp Borden or while hitchhiking on a Borden flight to Jarvis or to Aylmer’s No. 14 SFTS. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Most images in Lambie’s album have no written captions on the back, but they are in groups on pages which lead us to assume they were taken around the same time. This photo of Harvard 3176 is connected to the next photo in that they are in the same grouping on the page. More importantly, the pattern of snow and asphalt on the ground around the Harvard is also the same in both photos which means they were taken at the same time in the same place. This aircraft served with No. 14 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Aylmer, Ontario for its entire wartime career, so it’s likely that this photo was taken there as opposed to Borden which had First World War hangars. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Perhaps standing on the control tower’s catwalk or on a hangar roof, Don Lambie captures part of a Service Flying Training School flight line after a light early winter snowfall has been cleared. For reasons already stated, I feel this is at Aylmer. Fourteen yellow Harvard trainers are prepped and ready for students and instructors. Note the two wooden frames standing on the grass in the centre foreground next to Harvard 3176. These frames are visible, in the same positions, in the next photo. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A bare-metal Lockheed Model 12 (RCAF Serial Number 7641) taxies away from the flight line at an airfield on a sunny day in the spring of 1943 (note the dirty residual snow on the edge of the ramp). Used to move commanders, inspectors, staff pilots, accident investigators and even needed parts around the various Training Commands, the Lockheed 12 was used as a utility aircraft and not for training purposes. The Royal Canadian Air Force operated a small number of used examples of the type (also known as the Junior Electra) purchased from private owners in the United States and Canada. RWR Walker’s excellent and helpful RCAF serials website (Following Walker’s death, the site is now kept alive by The Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum) states that this aircraft was taken on strength with the RCAF in June of 1944 and then was put up for disposal in January of 1945. During that time span, Lambie was in Egypt and Italy, so the dates must be wrong. Lambie clearly took this photo a year previous. The wooden frames in the foreground can be seen in the previous photo which Lambie took after a snowfall, so we know this was definitely taken while Lambie was in training. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

From the control tower, Lambie snaps a photo a Lysander target tug. Not sure what’s going on here, but the lone yellow and black aircraft in this cold landscape seems to be attracting a lot of attention with at least eight men watching it warming up. This particular Lysander (RCAF serial No. 2316) served its entire life at No. 1 Bombing and Gunnery school at Jarvis, Ontario so I am placing it here in this section when Lambie was in Southern Ontario in January 1943. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

It’s difficult to tell, but the underwing RCAF serial for this winterized Tiger Moth is either 8889 or 8885. Either way, both of those Tiger Moths worked their service lives with No. 1 Training Command in Ontario. This was again likely photographed at the same time and Ontario location as the previous winter shots. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Initial Training School at No. 6 ITS, Toronto, Ontario

April 4 to June 12, 1943

Following Manning Depot, prospective aircrew like Lambie who had potential for pilot or navigator training were posted to an Initial Training School (ITS). It was here that they learned the basics of airmanship, aerodynamics, meteorology, mathematics and even some simple flight control and navigation in diminutive Link trainer simulators. The results of their tests at ITS determined their next posting. Everyone wanted to become a pilot, but many would not. Truthfully, if the RCAF was short on navigators or bomb-aimers, perfectly suitable pilot candidates could be sent to navigation or bombing and gunnery schools to fill the voids. The ITS courses demanded diligence and lots of study and often required an academic background beyond the limits of high school graduates. Lambie’s mathematics refresher courses at the University of Montreal in late 1942, it would have paid off here.

Tests also included an interview with a psychiatrist, the four-hour long M2 physical examination and a session in a decompression chamber. At the end of the course, the flight or navigation postings were announced. Occasionally candidates were re-routed to the Wireless Air Gunner stream at the end of ITS. Some students, deemed unsuitable for the complexities or pressures of aircrew work might be sent to train for ground support positions. There were seven Initial Training Schools in the BCATP with Lambie sent to No. 6 ITS in Toronto, a short train ride from Camp Borden. Since all ITS training was on the ground, the schools were housed in former educational facilities and seminaries. In the case of No. 6 ITS, courses were delivered at the Toronto Board of Education building

In the summer of 1943, Leading Aircraftman Don Lambie, having just completed Initial Training School, proudly strolls the streets of Montreal in his summer tunic, polished shoes and white cap flash denoting that he is now aircrew in training. He was granted the wish of every recruit — to train to be a pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force. Lambie had, for three years, listened to the stories of Canadian fighter pilots like Stan Turner, Willie McKnight and “Eddie” Edwards (nicknamed Stocky after the war) so was likely extremely proud to be in their company. The good-looking Lambie had no trouble attracting female companionship, but now, with his uniform and aircrew status, one can almost imagine the sound track and opening lyrics to the Bee Gee’s Stayin’ Alive playing as he walks down the street— “Well, you can tell by the way I use my walk I'm a woman's man, no time to talk” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Elementary Flying Training at No. 11 EFTS Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec

Course No. 63, June, 13 to August 7, 1943

Almost all of Lambie’s pilot training took place close to his home in Montreal’s Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhood—a luxury in the BCATP. Some students came from as far away as New Zealand to train in Canada, while others trained just far enough from home to make weekend visits there difficult. By early June, Lambie had just returned from a successful time at Initial Training School at No. 6 ITS in Toronto. From then on, his next three training postings remained in Quebec. The previous photo indicates that he had some sort of short leave in Montreal before heading off to his next assignment — approximately 8 weeks and 50 hours of basic flying training at an Elementary Flying Training School. In addition to basic manoeuvring — taking off, horizontal flight, approach and landing with engine on or off, etc. — Lambie was also taught some simple aerobatics such as rolls and loops. An EFTS student pilot was expected to go solo around the eight-to-ten-hour mark of dual instruction flight. Some did it sooner, and some were given a degree of leeway if they were struggling with a certain stage of flight (usually landings) but otherwise promising, but if the student was not cleared for solo flight by 12-14 hours, he could be washed out.

Again, Lambie lucked out when he was ordered to No. 11 EFTS near the North Shore city of Trois Rivières (in those days, English-speaking Montrealers would have simply called it Three Rivers). From here it was just a two-hour train ride back to Montreal. This meant that Lambie could visit his family if a 48-hour leave was granted. While at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Lambie was involved in a minor ground collision with another Fleet Finch. Another student, LAC Barrett in Finch 4547 collided with Lambie’s aircraft (4774) causing minor damage to the inter-plane struts. No one was injured.

While he was training at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, one of his instructors, Bruce MacDonald of Nanaimo, British Columbia impressed upon him the importance of committing to memory certain procedures that might one day save his life. In writing to MacDonald’s daughter following her father’s death in 2005, he stated:

One day when I was posted to Cap de la Madeleine in Quebec, the weather was terrible. So, the recruits thought they would get the day off from flying [although some of us were sorry we could not be flying]. Out of the blue came this very quiet spoken flying instructor [who happened to be my specific instructor] saying that we were to appear in the hangar for ground instruction! In the course of that instruction, came the procedure that in 1945 helped me to save my life north of Venice after my Spitfire was damaged by groundfire. Naturally I have great affection for your father and will always hold him in fond memories.

A study of Lambie’s log book reveals the incident he refers to in the letter to MacDonald’s daughter. On April 7, 1945 Lambie was flying a Spitfire Mk VIII (AN-X, RAF Serial No. JG337) on a 6-plane attack against seven barges in the industrial harbours of Marghera to the northwest of Venice. He dropped a 500 lb. bomb and made one strafing run during which his engine cut out after being damaged by groundfire. His logbook notes do not say what happened after that, but both he and JG337 survived.

Lambie would have 26 dual instruction flights with Warrant Officer MacDonald. The young instructor would release him for his first solo on June 25, 1943 after 10 hours dual instruction. Lambie makes no indication in his logbook of this momentous occasion, just the word “Self” written in the column under Pilot. In his first solo flight, he practised only two items from the EFTS syllabus: No. 7: Take-off into wind and No. 8: Powered approach and Landing. In other words: One complete circuit.

An overhead shot of the facilities of No. 11 Elementary Flying School at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River at Trois-Rivières. The school operated the Fleet Finch at first and then later instruction was given on both the Finch and the Fairchild Cornell. In this photo we see both Cornells and Finches on the flight line and around the parade square. As well, there appears to be an Anson and a Harvard on the upper ramp and Tiger Moths at the bottom of the image. The barracks where Lambie lived are at upper right. Photo via Flight Ontario

Lambie snaps a blurry shot from the front seat (note the strut at right) of his Fleet Finch trainer of what he would have called Three Rivers in 1943, but is now better known by its French name Trois-Rivières. It was the closest community to No. 11 EFTS at Cap-de-la-Madeleine. In the middle of the photo we see the distinctive shape of the Hippodrome race track and at bottom its bustling St. Lawrence River riverfront. The city, now the fifth largest in Quebec, stands at the confluence of the St. Lawrence and St. Maurice Rivers. “But that’s only two rivers.” you might say. The name comes from the fact that the St. Maurice River (upper right) coming down from the north, flows into the mighty St. Lawrence through three separate channels. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

At Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Lambie trained on Fleet Finches like the two aircraft pictured here. The Finch on the right (4723) was damaged at Trenton more than two years before this photo was taken, so perhaps it was repaired and assigned to No. 11 EFTS. Why Lambie is on the outside of the perimeter fence is not known, but he surely would have had access airside. For more on the Fleet Finch operated by Vintage Wings of Canada, click here. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Judging by the fencing in this photo, it was taken at the same time as the previous photo of the two Finches. It shows a a nice cross section of British Commonwealth Air Training Plan aircraft types parked along the fence and moving about on the ramp. In the foreground sits Avro Anson 8359, a Mk II built in Nova Scotia by Canadian Car and Foundry. The multi-engine training aircraft was assigned to No. 3 Training Command which was responsible for all training bases in Quebec and the Maritime provinces. Next to 8359 sits a North American Harvard IIB, (H40 with RAF serial FE842), and beyond that, a British-built Fairey Battle bombing and gunnery trainer sporting a white diagonal fuselage band with the numerals 54 on it side. In the distance, Fleet Finches are active on the ramp. Since Anson 8359 was released from five months of storage on August 2 of 1943, this puts the scene likely in August or September at No. 11 EFTS Cap-de-la-Madeleine where Lambie was completing his elementary flying training. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

While at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Lambie became close friends with one of his instructors, Flight Lieutenant George Morrison, who he would remain close friends with until the 21st century. In his log book, he has pasted a news clipping of Morrison’s wedding which occurred in January of 1944 while Lambie was in Bagotville, Quebec. Image via Donald Lambie’s logbook

Throughout the three years covered by the Lambie album there are numerous photographs of him in the company of beautiful young women — acquaintances, neighbours, military nurses and girlfriends. With his Hollywood good looks and ease with making friends, this comes as no surprise. The title of the album page where this photo appears states “Île Perrot, July 1943”, which means he was on leave there during his time at Cap-de-la-Madeleine — perhaps on a weekend pass. Île Perrot is a large island at the confluence of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Rivers, west of Montreal and its shoreline is populated by summer homes. Perhaps he was visiting the family of this woman. The handwritten caption on the back, obviously written by the young woman in the photo, reads“ I really don’t look like that, do I? What “muskles” on you!! When you’re lonely and sad, if ever, I’m sure this will revive you.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Service Flying Training at No. 13 SFTS, St. Hubert, Quebec

Course No. 87 — August 8 to November 26, 1943

There was a series of potential disappointments/setbacks a recruit might have to face as he went through aircrew training. Following graduation from Elementary Flying Training, most pilot trainees still held on to the dream of flying single-engine fighter aircraft in the RCAF. If, at this point, he was selected to train at a multi-engine Service Flying Training School, it was likely (but not always the case) that he would eventually be assigned to a Bomber Command squadron, where life expectancy was grim, to a Coastal Command squadron where patrols were monotonous or to a transport squadron where glory did not necessarily reside. Sometimes a graduate might go on to flying intruder aircraft like the Mosquito or Beaufighter, but single-engine fighters were now pretty well off the table.

Don Lambie’s luck continued when he was posted to a single-engine advanced flying training course at No. 13 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station St. Hubert due east of his home on Montreal Island, across “Le Fleuve”. St. Hubert, unlike most airfields of the BCATP, predated the Second World War, having been established in the 1920s as a civilian aerodrome for the growing civilian airline trade. He was now closer to home than ever, with only a half-hour drive across the massive Jacques Cartier Bridge to Longueuil and on to St. Hubert. He was close enough to date girls in Montreal while learning to fly across the river. And I’m sure he did.

His training here lasted another 19 weeks. In the first phase at an SFTS, the trainee was part of an intermediate training squadron; for the following phase, an advanced training squadron and for the final phase training was often conducted at a nearby Bombing & Gunnery School. In the end, when Lambie had his wings pinned on him on November 26th, 1943, he was fourth in the class of 68 students of Course No. 87, of which only 54 graduated, four having Ceased Training, while ten were delayed to the next course.

St. Hubert continued after the war as an important fighter base in the jet-powered Cold War and became the headquarters of Air Defence Command. Today, it is now part of la Ville de Longueuil, which in turn has become one of the most important aerospace centres in Canada, home to Pratt and Whitney Canada, makers of the ubiquitous PT-6 series turbo prop engines, Heroux-Devtek (landing gear) and the Canadian Space Agency. In 2017, Pratt and Whitney Canada completed its 100,000th engine — Aircraft flying with these engines had by then logged 730 million flight hours with 60,000 still-in-service engines operated by 12,300 customers in more than 200 countries.

Lambie, in a third aircraft, takes a photo of two other yellow Harvards from No. 13 Service Flying Training School flying in loose formation across a hazy landscape in Quebec. The school was situated near the South Shore community of Longueuil, across the river from Montreal. These aircraft have only the single occupant and one wonders if Lambie was also flying solo when he took this photo—something he would do in Hurricanes and Spitfires later in the war. They are overflying a very distinctive region to the east of the school known for several large mountains that rise from an otherwise flat alluvial plain known as the Collines Montérégiennes or Monteregian Hills, a series of eight butte-type mountains in the St. Lawrence River valley. The hills extend eastward for about 50 miles (80 km) from Île de Montréal to the Appalachian Highlands. The name, derived from the Latin Mons Regius (“Royal Mountain”), was first applied by Jacques Cartier, the French explorer, in 1535. That’s where Montreal gets its name. They range in height from 764 feet (Mont Royal in downtown Montreal) to 3,635 (Mont Mégantic). Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The Monteregian mountains today— from atop Mont Saint-Hilaire, receding into a similar haze as in the previous Lambie photo. Mont Rougement is next in line, with Mont Yamaska on the horizon at left and Mont Saint-Grégoire in the distance at right. Photo: Wikipedia

A poor photo but one that speaks to the conditions of flying from St. Hubert aerodrome in the winter of 1943 on the snowy South Shore of the St Lawrence River south of Ile de Montréal. While the vast majority of Harvards of the BCATP aircraft were painted yellow, this looks to be painted in a dark camouflage scheme as were some the RAF serial Harvards. We can just make out the pitot tube on Lambie’s Harvard in the lower right corner. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A classmate of Lambie’s flies close alongside in Harvard FE523 in the South Shore skies of Quebec. I believe this is similar to the camouflaged aircraft from the previous photograph (or likely the same aircraft). We can make out the yellow underside and the darker camouflage topside. Given the open cockpit and lighter dress of the pilot, I wonder if this is from an earlier, warmer time during Lambie’s SFTS training. Perhaps sometime between August and October of 1943. Taking photographs from the cockpit, especially during formation flying, was not necessarily encouraged, but Don Lambie seemed determined to keep a record of his war. Later, he would do the same while flying Hurricanes and Spitfires (both single-seat aircraft) while training. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Moments after the previous photograph, Lambie’s aircraft crosses beneath the yellow belly of Harvard FE523 while he snaps this photo. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

It’s difficult to positively identify the control tower depicted in this photo taken by Lambie. St. Hubert had a similar tower, but the previous photo reveals that St. Hubert’s structures seemed to be all painted white. This tower does not look like those at any base to which Lambie was posted — Borden, Cap de la Madelaine, St. Hubert or Bagotville. If anyone can positively identify this tower, please write to me. After his wings were awarded, his next posting was at Bagotville, but that station had a control tower that was attached to one of its hangars. I’ll place this photo here in the section about his Service Flying Training, but it could be anywhere — even taken in Ontario when he was doing Guard Duty. Of note is the radio/flying control truck parked on the ramp outside. These trucks, with their mobile control cabs, were used to supplement air traffic control, especially at relief fields with no tower facilities. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

On the day he received his wings at St. Hubert, Lambie was featured along with 14 of his fellow airmen and one army officer in the pages of The Montreal Daily Star newspaper. Lambie is dead centre. Sergeant R. B. Gray (Left back row) is the same Bob Gray who took War Emergency Training Plan courses with Lambie at University of Montreal in 1942. Tragically, the only one of these men to die in the war was army Lieutenant Henry James Stuart O’Brien, who quit the Army and joined the RCAF. He would be killed almost exactly a year later flying a P-51 Mustang on a recce op over the Ruhr Valley. Clipping via Donald Lambie Collection

A cautionary tale. On the last page of Lambie’s logbook section devoted to No. 13 SFTS, he pasted a small news clipping which he came across in the Montreal papers in January of 1944 when he was at the Hurricane OTU in Bagotville. Just three paragraphs long, it named Flight Lieutenant J. F. Kosalle of Toronto as the young Harvard flying instructor from St. Hubert who was dismissed from the RCAF after a court martial that found him negligent in the deaths of two Canadian Army officers and injury to four others. The accident in question happened during a demonstration of what we now call close air support at Camp Farnham, an army training base in the Eastern Townships, south east of Montreal. Kosalle and other pilots were engaged in a very low mock strafing run but Kosalle was lowest of all and struck six standing officers with his port wing and propeller. Two were killed instantly, while the other four were severely injured. On top of that, an ambulance rushing to bring victims to the Camp Hospital swerved to avoid troops on the road and overturned in a ditch. This tragedy happened on August 5, 1943, just two days before Lambie got to St. Hubert. After an investigation, Kosalle was court-martialled on October 12, but his name was not released to the public until early January. This story must have made a deep imprint on Lambie as he was commencing his service flying training. Kosalle was a good man, who had worked so hard for his wings that he graduated top in his class at Dauphin, Manitoba… all that hard work and achievement to be dashed and covered in shame for one moment of poor judgement. War is hell. Training for war is hell too.

A terrific photo of Lambie sitting casually on the wing root of a Hurricane named SALOME. According to the hand-written caption on the back, this was taken at St. Hubert in November of 1943 after his assignment to the Hurricane OTU. This would have been just days after he got his wings, as he is wearing an officer’s cap.Perhaps the Hurricanes were at St. Hubert to inspire the next course of Hurricane students. The pride and excitement for the next few months of fighter training is easy to see. SALOME was likely named after another popular song from the early 1940s by British band leader Harry Roy and his band. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

My heart skipped a couple of beats when I saw this photo taken at St. Hubert of one of Lambie’s pals standing in front of a Hurricane with the words “STAR DUST” on her cowling. "Star Dust" was a popular jazz song from the late 1920s composed by American singer, songwriter and musician Hoagy Carmichael. The Vintage Wings of Canada Hurricane XII (5447), which was also at Bagotville during Lambie’s time had those words painted on its cowling too, but in a different font and with a large yellow number 71. There is no way to tell which aircraft this is or if indeed the cowling on our Hurricane came from 5447 originally. Perhaps there were two or more STAR DUST Hurricanes, or maybe it was repainted after sustaining damage. We will never know. As well, it appears that the “Salome” Hurricane is in the background. We can just make out the nose art on her cowling. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A photo of Hurricane XII 5447 “Star Dust” with Harry and Anna Whereatt on the their Assiniboia, Saskatchewan farm in 1993 during a visit by the Canadian Aviation Historical Society. This aircraft is now fully restored by Vintech Aero/Vintage Wings of Canada as the Willie McKnight Hurricane. Is this the same aircraft from the previous shot? Photo from Angie McNulty

Another photo of Lambie and a young woman named Tess together in 1943. Given that Lambie is now clearly an officer, this places the photo in Montreal shortly after he received his wings at No. 13 SFTS, St. Hubert, or on some leave from Bagotville during the later winter. I would bet this was from the end of November 1943. Lambie’s course at Bagotville would not start until December 13th and his “Record of Service Airman” records that he was granted two weeks leave following his wings parade. One thing that strikes me immediately is how perfect his dress is. His light blue shirt looks bespoke, his tie knotted with experience and style, his greatcoat and cap right out of the box. Lambie looks the perfect officer and gentleman. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Hand in tunic pocket, Pilot Officer Donald Walter Lambie, RCAF of Montreal, Quebec, son of David and Edith Lambie, strikes a confident pose while on leave in the winter of 1943/44. Prior to his leave in Montreal, Lambie was pinned with his wings at St. Hubert on the afternoon of November, 26th by Wing Commander Georges Roy, DFC. Roy, a Bomber Command squadron commander. Roy had just the month before been CO of 424 Squadron in Tunisia from where the squadron’s Vickers Wellingtons were attacking targets in Italy. After 32 ops, he was home for a rest, a short war bond tour and then given the honour of placing wings on Lambie and his course mates at St. Hubert where in 1940, he had been a flying instructor. Coincidentally, he had been an instructor at Cap-de-la-Madeleine as well. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

There is a page or two in Lambie’s album dedicated to the day, not long after after his commissioning, when he visited this couple and their three boys. He had no relatives in the immediate area, so perhaps these were neighbours, friends of the family or a work mate. Given that they are in their Sunday best, perhaps this is, in fact, Sunday and everyone is heading to or from church The couple and their boys, turned out in tweeds, plaid ties, plus-fours and knee socks, stand in front of their 1939 Dodge two-door sedan. The photo speaks to the socio-economic stratum that Lambie came from — solidly middle class, educated, urban. In Canada during the Second World War, it did not matter what socio-economic class you came from, the level of education you had reached or your religious background—everyone offered up their services and even lives to the cause. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The returning hero. Lambie has yet to fly fighters or indeed get more than a few hundred kilometres from his hometown of Montreal, but I doubt that was significant to these three young brothers posing with him in front of their porch. Having grown up through the last three years of the war with their boy’s life books, newspaper comics, and serialized stories filled with the derring-do of RCAF fighter pilots like Montreal’s George Beurling, these boys must have been in awe of the young officer in blue. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Operational Flying Training on Hurricanes at No. 1 OTU, Bagotville, Quebec

Course #22 December 11, 1943 to March 25, 1944

The next stage in Donald Lambie’s quest to become a fighter pilot was conducted at an Operational Training Unit where he would learn to fly a frontline fighter and then learn how to use it as a weapon. There were two paths this could take for a would-be RCAF fighter pilot. He could ship out immediately for Great Britain where he would attend a Hurricane or Spitfire OTU, or he could be posted to Bagotville, Quebec which was the only fighter OTU in Canada. Bagotville was equipped with Harvards for refresher flying and skills assessment and the Hawker Hurricane Mk XII, a 12-gun Canadian-built variant of the British icon of the Battle of Britain. They would have to master this complex machine under tough flying conditions in a rugged and unforgiving environment. Graduates of the Bagotville OTU would then be channeled in one of two ways. Many would be posted to the numerous Hurricane-equipped RCAF fighter squadrons of the Home War Establishment and tasked with patrolling and defending the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Canada. Other graduates, like Lambie, would be sent directly overseas to Great Britain where they would wait at the RCAF Personnel Reception Centre at Bournemouth for a posting to a Spitfire OTU in England or possibly in the Middle East, thereafter to replace pilots lost through attrition or timed-out in both RCAF and RAF squadrons.