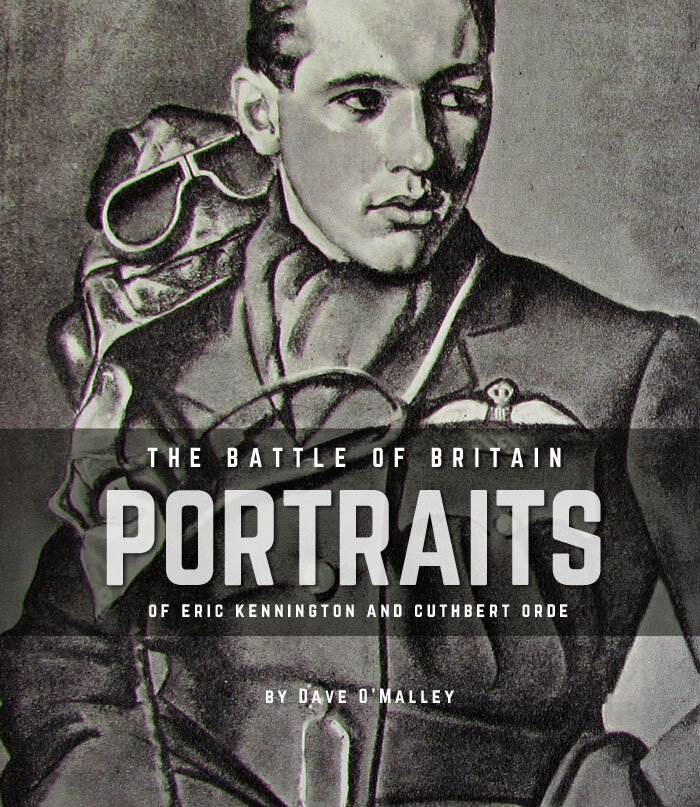

THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN PORTRAITS

There is a certain indefinable, yet physical, series of facial phenomena that happens to very young men engaged in a battle in which there is a distinct possibility they may be killed or horribly wounded. Their faces become leaner, the features more taut, the eyes more distrustful, the skin prematurely lined, the countenances more... well, beautiful. Even the most homely of these men carry the “look”—that mixture of toughness, loneliness, determination, distance, fear, experience and confidence that gives to their once boyish faces a look of indescribable strength, character, sorrow and virile beauty.

Over the past ten years, researching and mining the Internet for background material and images for our stories, I have viewed thousands upon thousands of photographs of RAF pilots and aircrew. The photographs depicted young men in two ways—either the formal post-wings parade studio photographs taken for family and girlfriends or candid personal record shots of young men, beaming and exuberant, during their training days; wistful, tired and deeply aged just months later, after combat took its toll. These photographs, especially the personal snapshot, have a certain truth that is ours to interpret, leaving us to sort out the meaning of the smile, the reason behind the look of exhaustion, the story in the old eyes in a young man’s body.

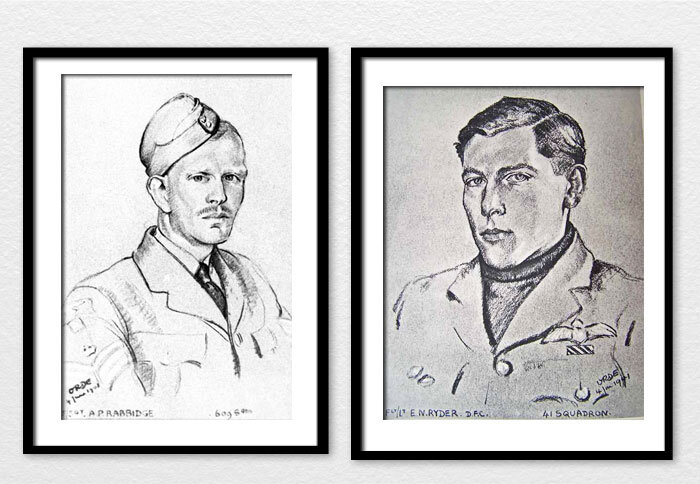

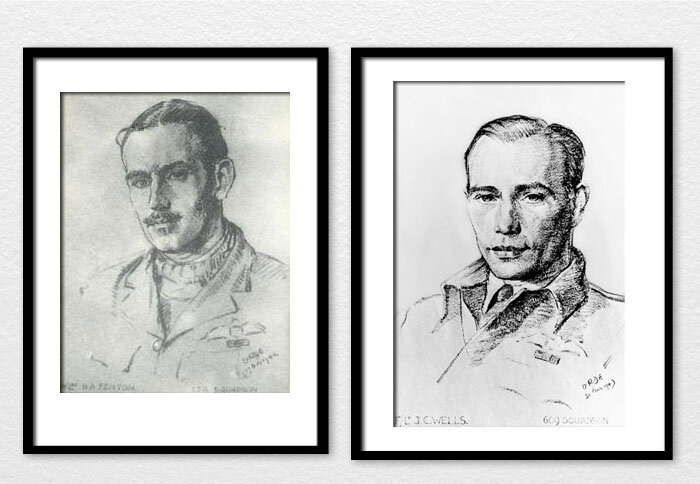

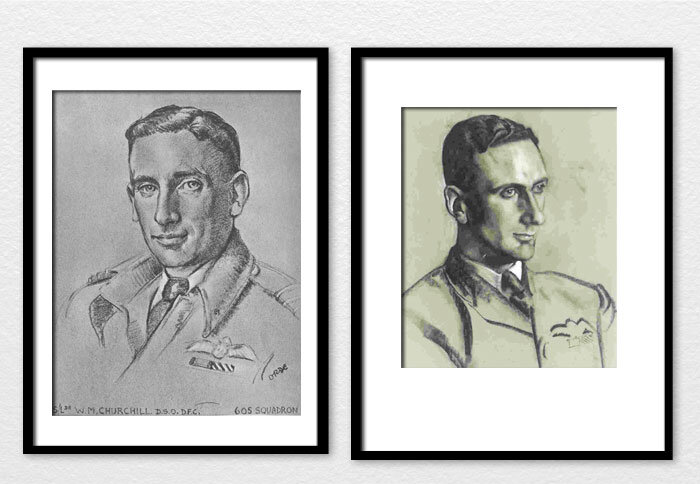

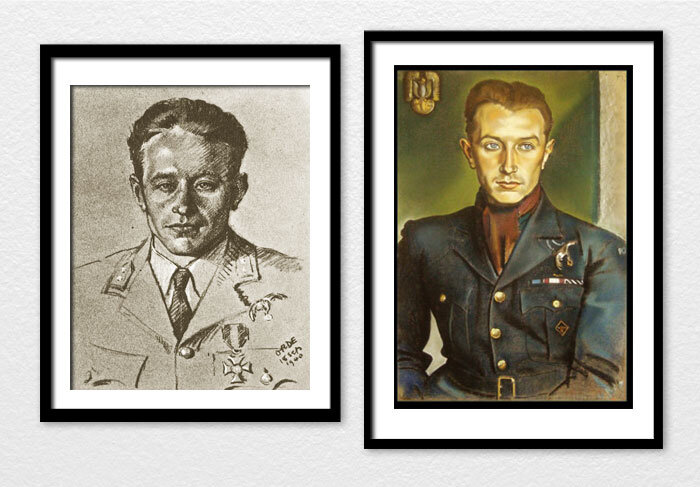

From time to time, I would come across a portrait in charcoal or pastels that seemed to say something entirely different about an aviator—something that a photograph could not. As time went on, I began to save these portraits in a folder. Soon, I had more than forty such images of artists’ portraits. There were a number of portrait war artists whose works were in this folder, but the great majority of them were done by two men—Eric Henri Kennington and Cuthbert Julian Orde—during a period beginning during the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940 and ending in 1944. The great majority of these portraits were of airmen who participated in, or were peripheral to, the Battle of Britain—either as leaders or contemporaries engaged by Bomber Command.

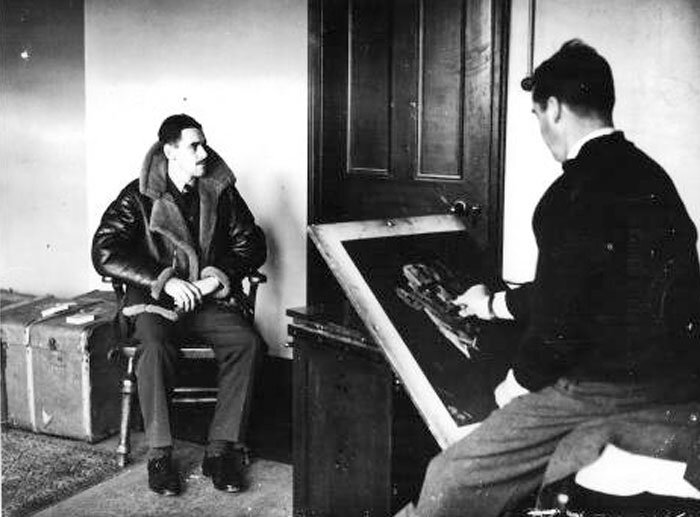

The subject of a studio photograph was asked to sit still for only a few seconds at a time, usually in the same lighting as every other subject. These photographers were, for the most part, true craftsmen, whose photographs were gorgeous expressions of light and manhood, considerably better than the average Walmart photographer that families flock to at Christmas time these days. But a sitter for a portrait artist like Kennington or Orde was required to sit for hours, even days, at a time. Often the artist would spend some time with his “sitter” or subject, getting to know him, allowing him to relax, to feel a certain ease. The act of simply being yourself and sitting for hours at a time seems to bring to the surface inner strength, nobility, weakness, sorrow and perhaps that person who dwells inside—the aggressive pugilist in New Zealander “Al” Deere, the smiling, almost sneering, disdain of Englishman “Archie” McKellar, the pain and sadness in the eyes of John Boulter.

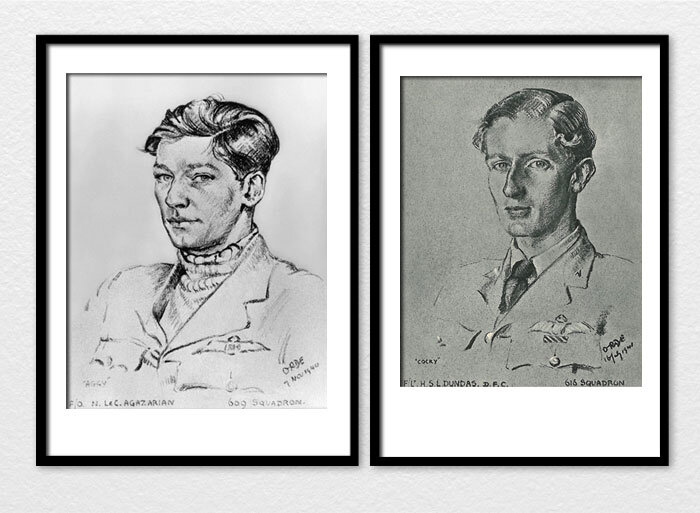

Not long ago, I started to search the Internet specifically for portraits done by either Orde or Kennington and I was astonished, or rather gobsmacked, to discover the sheer amount of portraiture work each of these fine artists had created during the Second World War. One of the finest resources for me was the fabulous Battle of Britain London Monument (BBLM) website which lists, by country, every pilot who participated in the Battle of Britain, along with biographies of varying completeness and, where possible, photographs and images of any portraits painted of the subject by Orde or Kennington. The work that the team at the BBLM site has done is nothing short of awe-inspiring. They have come very close to collecting the personal stories of each of the nearly 3,000 pilots who participated. I highly recommend you take an hour or so to visit the site.

I decided that I would make an online repository for as many of their portrait works as I could assemble. Kennington was a prolific portraitist with many military portraits of men and women of the other services and even civilian war workers, but this repository would be only for airmen. Orde also did many war art works other than portraits. As the war began to produce a long list of heroic and tragic individuals, both Orde and Kennington, recognized war artists and former military men, were contracted by the Royal Air Force to do portraits of airmen—mostly pilots and senior commanders. For the most part, the RAF selected the sitters, mostly based on their successes as fighter pilots or leaders. These young men would pay a visit to the artist’s studio, or in the case of many of the subjects, at the Air Ministry in London where a small studio had been set up for the purpose.

It cannot be overstated that having one’s portrait commissioned by the Royal Air Force and being invited to the Air Ministry to sit, was a high honour for any of these young men. Author and art historian Jonathan Black, in his definitive work on Kennington: The Face of Courage: Eric Kennington, Portraiture and the Second World War, wrote of one particular Blenheim pilot who wrote to Kennington to express his gratitude: “Words cannot tell you how much I appreciate your portrait, or the privilege I feel at having the honour to sit for you. It is so incredibly like me and yet, I wish I had half the character you have portrayed and when I look at it, I know that it is the character that I want to be rather than who I am…”

John Boynton Priestly, author and social commentator, who wrote the introduction to a book which included some of Kennington’s portrait work, said this in The Face of Courage about the men who sat for the artist: “… I think that it can be said that they truly represent the middle classes from which they are drawn… These are some of the young men who are not only battling in the skies to preserve our present freedom but will also, with any luck, be among those who will help to build the future Britain.” Sadly, of the 98 portraits that follow, half the young sitters were dead by the end of the war or shortly thereafter, in accidents in the new jet age.

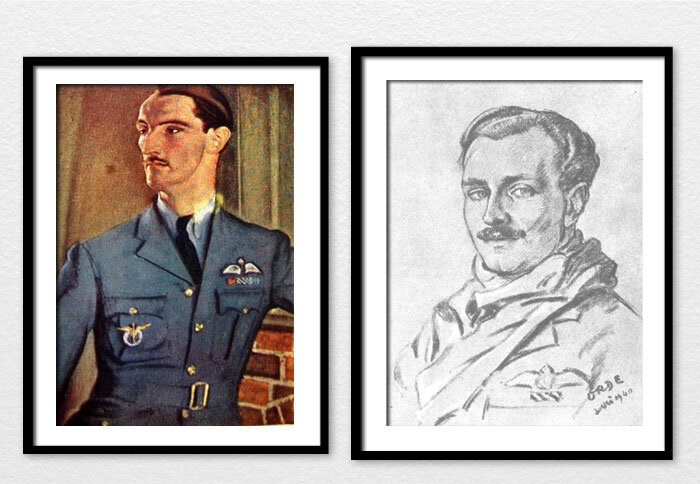

For my taste, the works of Kennington, dramatically impressionistic, stylish and heroic, inspire more emotion in me than Orde’s. At times, the sheer volume of Orde’s work and his robotic style comes close to what you might see from one of those gifted mall artists. But where Kennington’s sitters, for the most part, exude strength and heroic dash, Orde’s works display a wider range of emotions—doubt, exhaustion, aggressiveness and even fear. Both men captured something we cannot see.

It is important to state a few things about this repository of images of the works of Orde and Kennington. Firstly, some of the images which I found on the Internet are merely details from a slightly larger work (as in Geoffrey Tuttle’s portrait) and in almost every case, the colour is not correct. The edges of the art boards are cropped off in most cases, though this does not impact the work to any great extent. In several, the original is a colour pastel or oil work, but the only image found was a scan from a black and white reproduction in a book. These are quite simply the only scans from the original work that I could find.

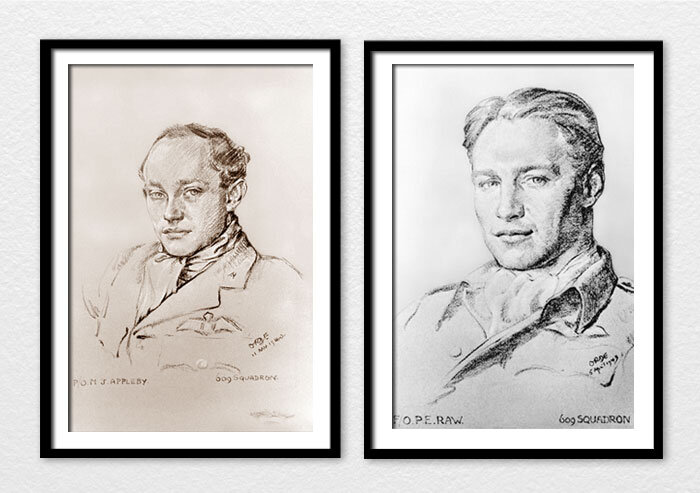

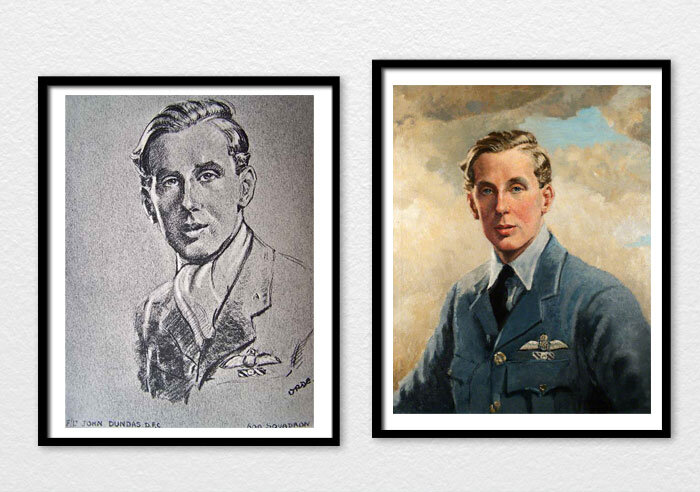

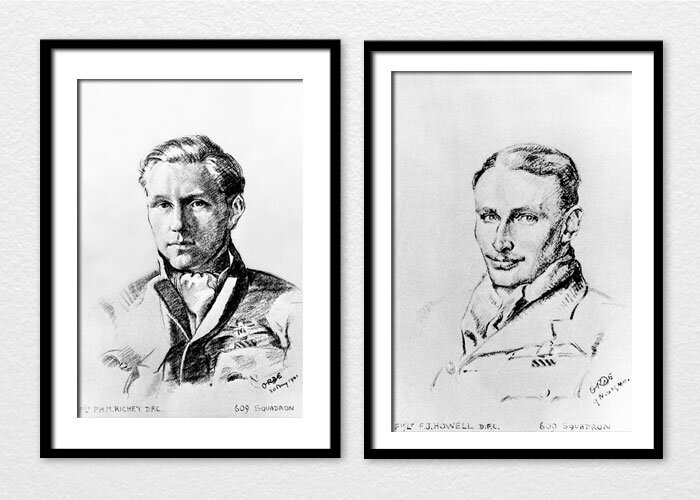

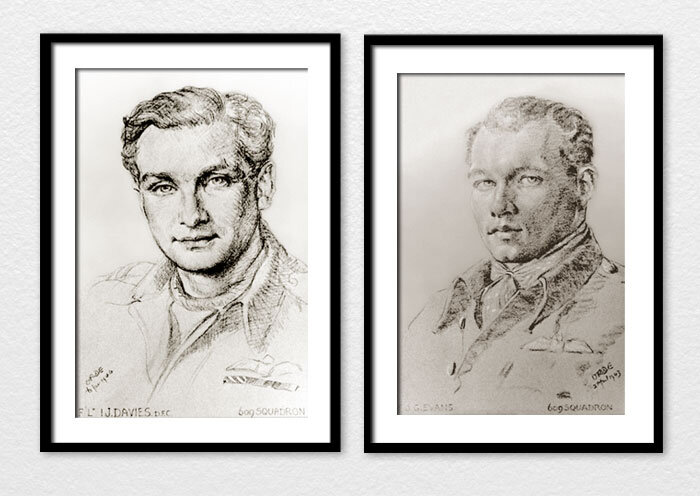

Not all the images in this collection are of sitters who participated in the Battle of Britain. Many, like the 609 Squadron pilot series by Cuthbert Orde were done months and even years later, but they certainly find their roots in the Battle of Britain work that he did.

For me, this repository is like an art exhibit of the work of two of the greatest war artists of the Second World War. To allow their works to be seen in this light, I placed each piece in a frame and matte, and “hung” them on a wall, two at a time. Perhaps that is corny... but I like the effect.

It is also important to emphasize that these are by no means all the works in this niche by either artist and that if someone should take offense by the inclusion of one or more of the works, I would be happy to remove that piece or pieces. And, on the other hand, if someone would like to draw my attention to another for inclusion, by all means send it and perhaps the airman’s biography to accompany it. The biographies themselves are intentionally light, some longer than others for no particular reason. For information, I sourced histories from wikis, the Imperial War Museum, RAF Museum, BBLM and squadron association websites, blogs, forums and personal memoirs. I make no claim that they are authoritative in any way. They are meant to illustrate the depth of the service each man offered up. Should anything I included not be factual or incorrect in anyway, I would be delighted to hear from you and make the correction. The intention is to do honour to both Orde and Kennington and their sitters.

The biographies of each airman include the Gazetted Commonwealth decorations which they were awarded... to the best of my knowledge. They do not, however, include those decorations awarded to them from other nations such as Poland, France, America or Holland. Many of these great men were awarded these equally important decorations, but for brevity, I left them out. One can always search for these men on the Internet to see the additional “gongs” they were awarded.

Now, with all these caveats out of the way, let’s look at some powerful work. These were the Few, some of the finest men of the Second World War. None of them are alive today.

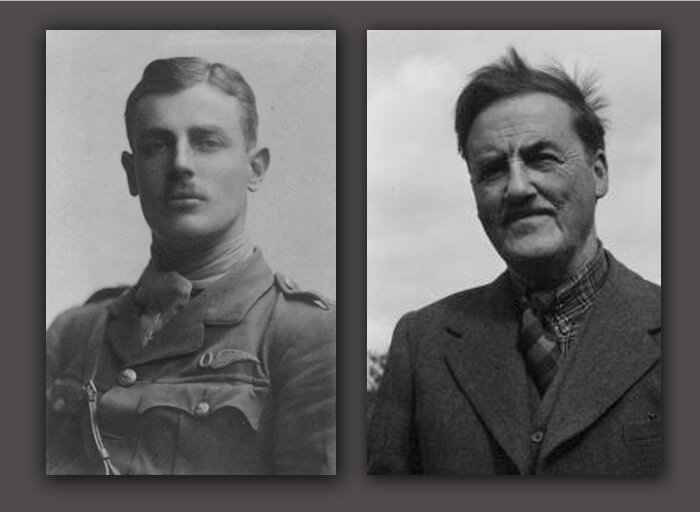

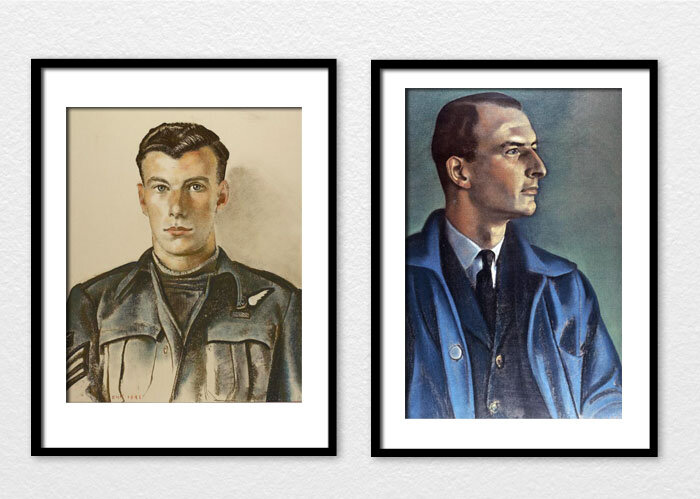

Both Cuthbert Orde (left) and Eric Kennington (right) were veterans of the First World War. Orde was a pilot and Flying Officer (Observer) with the Royal Flying Corps flying Maurice Farman aircraft. Two of his brothers also fought during the war. His brother Herbert was killed on HMS Goliath when it was torpedoed near the Dardanelles in May 1915 and his brother Michael, a pilot, was shot down in 1916 and captured. He was killed in a flying accident in 1920. Eric Kennington, like Orde, was born in 1888 and served in the war, fighting with the 13th Kensington Battalion, London Regiment. He was wounded while fighting on the Western Front and while recovering, he painted a large canvas, entitled The Kensingtons at Lavantie—of his unit resting and exhausted after battle. The painting made him an instant celebrity in art circles and after he recovered, he was sent back to the line, this time as a war artist. Photos: Orde, Wikipedia; Kennington: London Transport Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

Both Cuthbert Orde (left) and Eric Kennington (right) were veterans of the First World War. Orde was a pilot and Flying Officer (Observer) with the Royal Flying Corps flying Maurice Farman aircraft. Two of his brothers also fought during the war. His brother Herbert was killed on HMS Goliath when it was torpedoed near the Dardanelles in May 1915 and his brother Michael, a pilot, was shot down in 1916 and captured. He was killed in a flying accident in 1920. Eric Kennington, like Orde, was born in 1888 and served in the war, fighting with the 13th Kensington Battalion, London Regiment. He was wounded while fighting on the Western Front and while recovering, he painted a large canvas, entitled The Kensingtons at Lavantie—of his unit resting and exhausted after battle. The painting made him an instant celebrity in art circles and after he recovered, he was sent back to the line, this time as a war artist. Photos: Orde, Wikipedia; Kennington: London Transport Museum

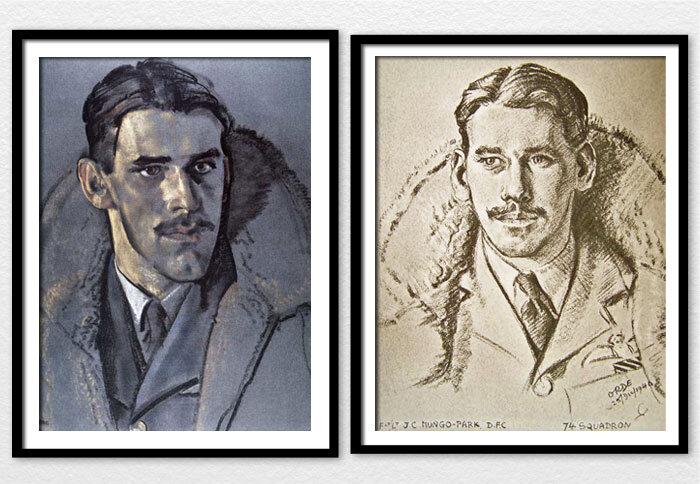

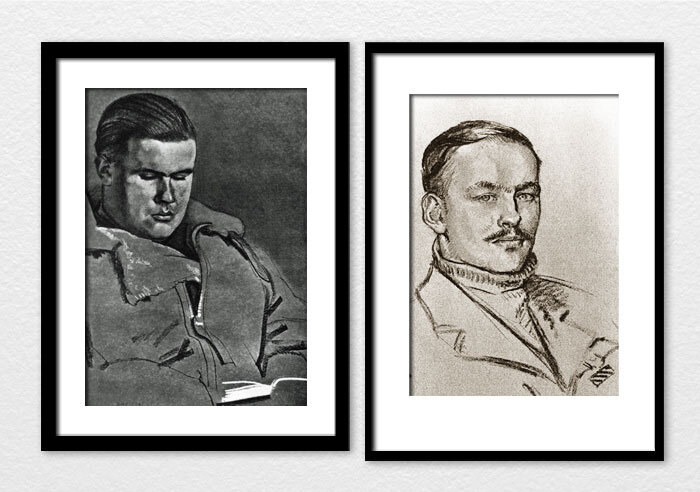

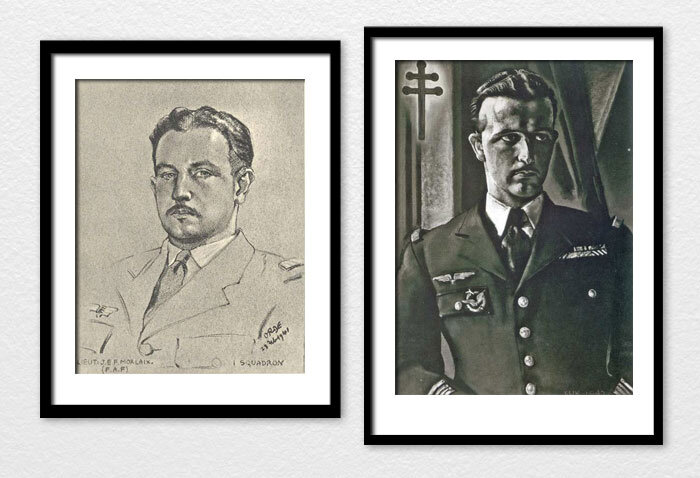

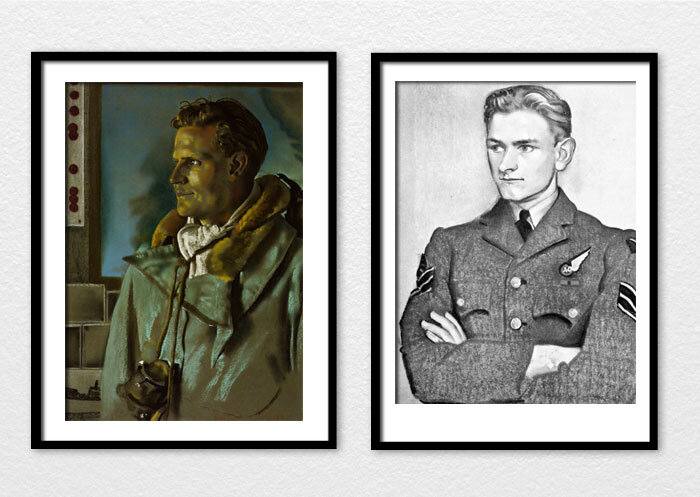

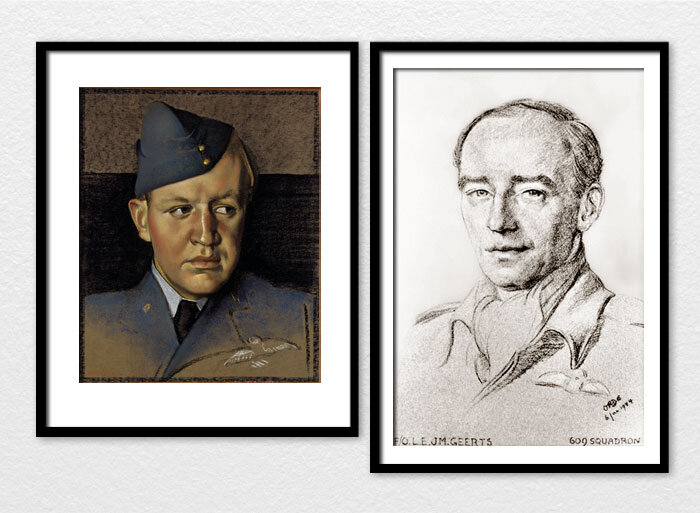

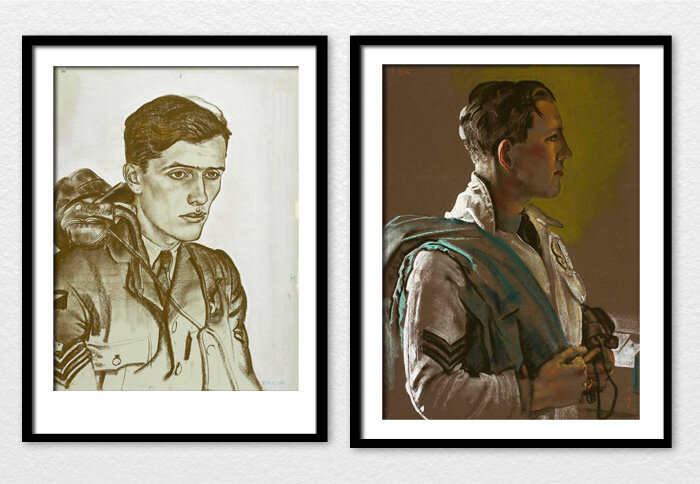

Two sketches of John Colin Mungo-Park, DFC and Bar—Kennington’s on the left, Orde’s on the right. Mungo-Park joined the RAF on a short service commission in June 1937. His early assignment was as an anti-aircraft cooperation pilot attached to the Fleet Air Arm, flying the Fairey Swordfish. When war was declared, he transferred to Spitfires with 74 Squadron at RAF Hornchurch under the command of “Sailor” Malan. He flew throughout the Battles of France and Britain, becoming a double ace with 11 aircraft destroyed, 5 probables, and four damaged. Squadron Leader Mungo-Park, 74 Squadron, was killed in June of 1941 when his Spitfire was shot down over Adinkerke, Belgium. He is buried in Adinkerke Military Cemetery, just 60 miles from where is father, Lance Corporal Colin Mungo-Park, killed in the First World War, lay buried. Images via Battle of Britain London Monument

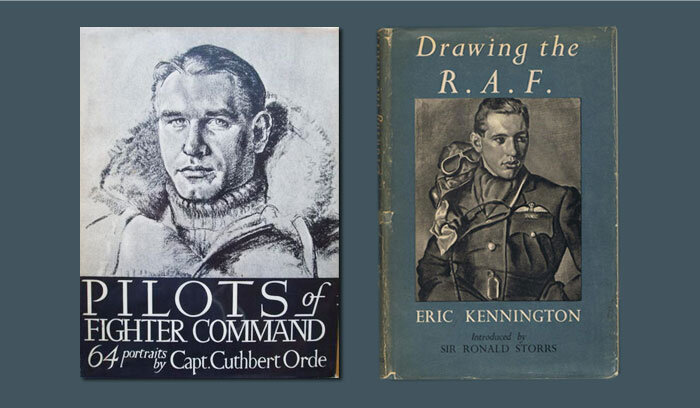

Cuthbert Orde and Eric Kennington both produced books after the Battle of Britain which featured their sketches, drawings and paintings of the Battle’s pilots. It is interesting to note that both Orde and Kennington chose a non-British fighter pilot to grace their covers. “Sailor” Malan, a South African, graces the cover of Orde’s Pilots of Fighter Command, while the Canadian “Willie” McKnight is featured on the cover of Kennington’s Drawing the R.A.F. Many of Orde’s sketches also appeared in Some of the Few, by John P.M. Reid, published in 1960. Images via internet

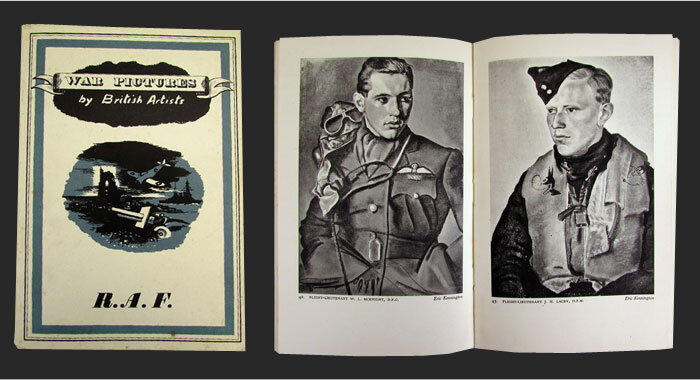

Eric Kennington’s colour pastel and chalk portraits were reprinted in black and white for this period booklet of war artists. One two-page spread features two of the great aces of the Battle of Britain—Canadian “Willie” McKnight (left) and James Harry “Ginger” Lacey. McKnight was the highest scoring Canadian and Lacey the second highest scoring British pilot of the Battle. Photos: Georgina Lander

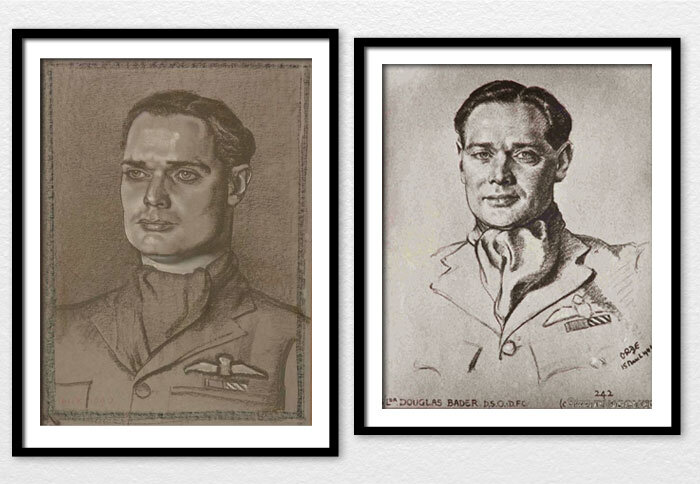

Several pilots of the Battle of Britain and later conflicts were painted or drawn by both Cuthbert Orde and Eric Kennington—case in point, Squadron Leader (later Group Captain) Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader, CBE, DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar, MiD x 3,the famed legless fighter pilot of the RAF. Born in 1910 in London and raised in India, he joined the RAF in 1928 with a cadet posting to the RAF College at Cranwell. He joined 23 Squadron at RAF Kenley, flying the Bristol Bulldog. In 1931, whilst practicing aerobatics, he crashed attempting to roll his Bulldog at low level. He survived but lost both of his legs. While he remained in the RAF, he was not allowed to fly for what most would think to be obvious reasons. He left the RAF after a couple of years and joined Shell petroleum. When war broke out, he pestered the RAF to return to flying status and, despite his obvious handicap, passed several flying tests and was certified combat ready. He joined 222 Squadron and fought in the Battle of France and at Dunkirk, and showed himself to be a tenacious and very capable fighter pilot. In June 1940, he was given command of 242 Canadian Squadron, a unit with low morale following the Battle of France. He soon turned them into one of the finest squadrons of the Battle of Britain. Jonathan Black, in his book The Face of Courage: Eric Kennington, Portraiture and the Second World War, writes about Kennington’s feelings about Bader: “While drawing Bader and some of the pilots under his command, Kennington wrote to his brother: “I’m having a terribly good time. It’s more stage-like than I ever imagined. The OC here (Bader) has no legs and has been passed 100% unfit. But he is back and tears up into the sky like a hawk and nearly pulls the Germans out of their airplanes with his teeth and all his squadron have about a dozen each to their credit. I had forgotten we could produce such tigers...” ”

His tenacity and ability to lead men into battle marked him for promotion, and he left 242 in March 1941 to become Wing Commander (flying) at Tangmere. On 9 August, he was shot down, bailing out of his Hurricane and leaving one of his legs behind in the process. The Luftwaffe permitted the RAF to fly a truce mission to deliver a spare leg for Bader, but they soon wished they had not. Bader proved to be a difficult prisoner, attempting several escapes and he was soon sent to Colditz Prison (Oflag IV-C) where he joined other “incorrigible” prisoners. After the war, he flew with the RAF for a year, but retired and went to work for Shell Petroleum as manager of their fleet of aircraft. He fought tirelessly on behalf of physically handicapped children and remained a loyal friend to his many squadron friends. He died in 1982.

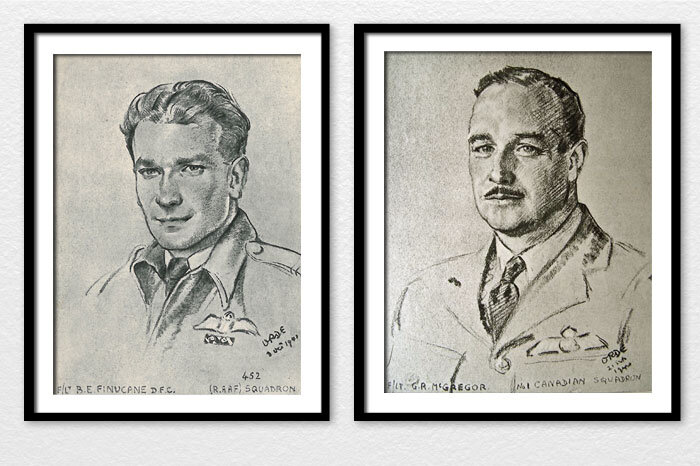

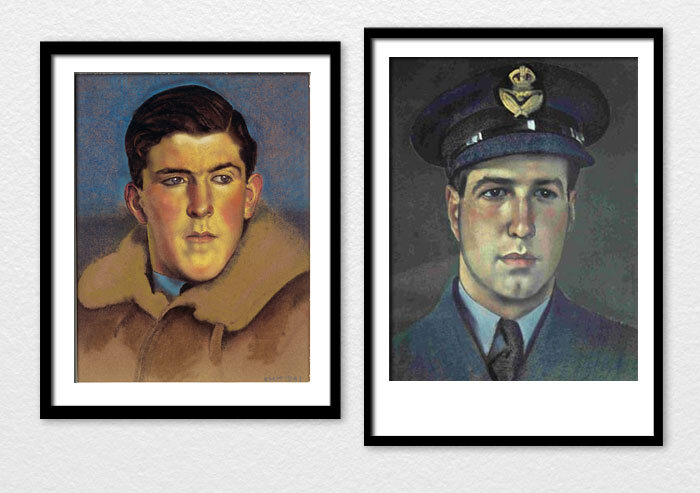

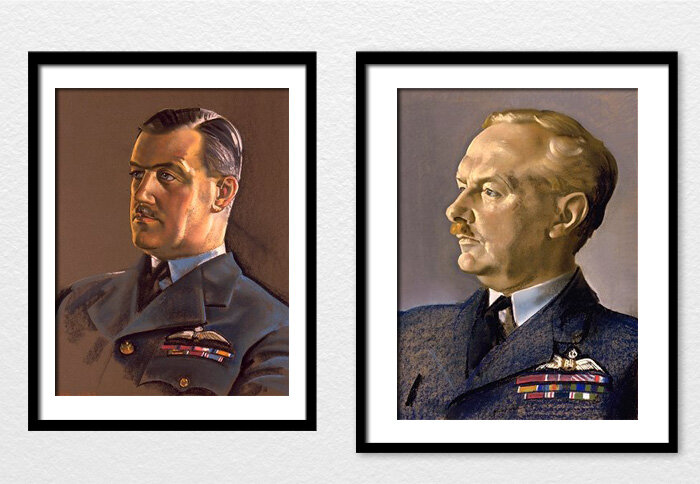

Two sketches by Cuthbert Orde—Wing Commander Brenden Eamon Fergus Finucane, DSO, DFC and two Bars (left) and Group Captain Gordon Roy McGregor, CC, OBE, DFC

“Paddy” Finucane, from Dublin, Ireland, was one of the most revered and capable of the early fighter pilots during the Battle of Britain and the following offensive ops over occupied France. Though Catholic and brought up in the “Early Troubles” and the Irish Civil War, his family moved to England and he developed an interest in aviation. His final tally was 28 victories, 5 probables and many more damaged. Finucane rose quickly to the rank of Wing Commander but was killed on 15 July 1942 when his Spitfire, which had been hit earlier over France, suffered an engine failure. Finucane ditched in the English Channel, but was killed or drowned. More than 2,500 people attended his memorial service at Westminster Cathedral. His name is inscribed on the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial, commemorating airmen lost in the Second World War who have no known grave.

Group Captain Gordon McGregor (a Squadron Leader by the Battle’s end) of Montréal, Québec learned to fly in the early 1930s after earning a degree in engineering from McGill University. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1936, receiving his wings two years later. The handsome McGregor was the oldest Canadian-born pilot in the Battle of Britain, becoming a Hurricane ace during the Battle with 401 Squadron (then called 1 Squadron) RCAF. With five confirmed victories, he was the squadron’s top scoring fighter pilot. McGregor’s Second World War career would include commanding X Wing—a Canadian wing of Kittyhawk fighters on operations in the Aleutians. Later, towards the end of the war, he commanded 126 Wing, a Canadian Spitfire Wing in Europe. After the war, he went to work as an executive for Trans-Canada Air Lines, becoming its president a few years later. He then was instrumental in transforming TCA into Air Canada, today still the largest airline in Canada.

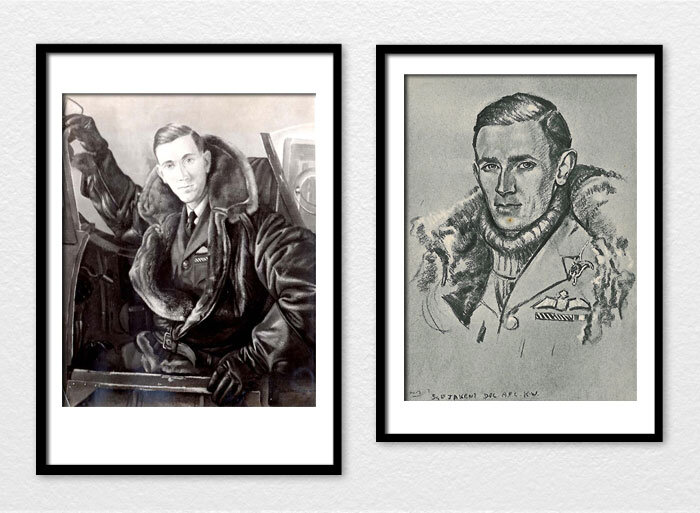

Both Cuthbert Orde (right) and unknown-portraitist John A. Mossbridge (left) took a shot at a “Johnny” Kent portrait. Winnipeg-born Group Captain John Alexander “Johnny” Kent, DFC and Bar, AFC, is a true legend of the Battle of Britain. He was born in 1914 and learned to fly at the Winnipeg Flying Club in 1931 at the age of 17. He joined the RAF in 1935 and his first flying assignment was with 19 Squadron on Gloster Gauntlets, followed by the Royal Aircraft Establishment at RAF Farnborough. It was here that Kent deliberately crashed his aircraft into various barrage balloons—300 times!!! For his sterling service as a test pilot, he was awarded the Air Force Cross. He began his flying war as a Spitfire photo-recon pilot with the Photographic Development Unit. He was shot down whilst on a low-level sortie in France, but survived. He then joined 303 Polish Squadron, RAF in command of “A” Flight. He earned the love and admiration of his Polish pilots, many of whom spoke no English. He eventually led the entire Polish Wing of four squadrons, thereby earning himself the nicknames Kentowski and Kentski. Of the four Polish squadrons in his charge, he had this to say: “I cannot say how proud I am to have been privileged to help form and lead No. 303 Squadron and later to lead such a magnificent fighting force as the Polish Wing. There formed within me in those days an admiration, respect and genuine affection for these really remarkable men which I have never lost. I formed friendships that are as firm as they were those twenty-five years ago and this I find most gratifying. We who were privileged to fly and fight with them will never forget and Britain must never forget how much she owes to the loyalty, indomitable spirit and sacrifice of those Polish flyers. They were our staunchest Allies in our darkest days; may they always be remembered as such.” Kent accounted for 13 enemy aircraft shot down. He survived the war, retiring as a Group Captain, working in the business world, and eventually dying in 1971 in Germany. In his portrait by Orde, he appears to be wearing a Polish pilot’s brevet suspended just above his RAF wings.

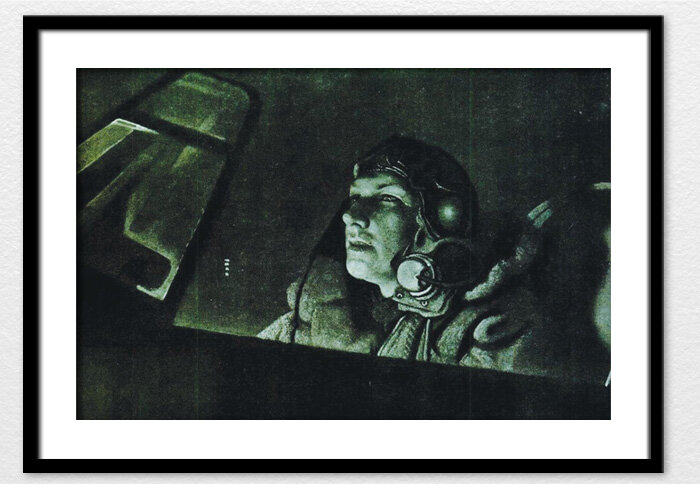

For many reasons, this is my favourite of all of Kennington’s (or Orde’s) portraits of pilots in the Second World War, for it shows a pilot in his element—the cockpit of his Hawker Hurricane night fighter as he prepares for takeoff. His face is lit from below by the lights of his instruments and the lighting in his dispersal area. The pilot in this study called “Night Flyer at Readiness” is Flying Officer Richard Playne Stevens, DSO, DFC and Bar. Stevens was born in 1909 in Tonbridge, Kent, one of five brothers and one sister. In his late teens, he worked on a cattle ranch in Australia and then later as an officer with the Palestine Police. In 1936, he returned to England, took flying lessons and then took a job flying with commercial airlines, mostly flying at night and across the English Channel. He joined the RAF Auxiliary in 1937 and was accepted permanently with the RAF in 1939. At 30 years old, he was at the upper limit for new officers hoping for a flying career. His more than 400 hours as a night passenger and mail pilot made him a good candidate for a night flying position however. His early RAF assignment was flying de Havilland Rapides (the same type he flew commercially) on searchlight and anti-aircraft artillery tests at night. Stevens’ first operational posting was 151 Squadron in October of 1940—one of the new night fighter specialist squadrons. Stevens’ first victory came on the night of 15–16 January 1941 and he went on to become one of the finest night fighter pilots of the war with 14 confirmed victories. Later he joined 253 Squadron, flying Hurricane night intruder and night fighter missions and in mid-December 1941 he failed to return from a night mission over Holland. The next day, German soldiers found the wreck of his Hurricane (and his body) and that of the Junkers Ju 88 he had shot down just 600 metres apart. He apparently flew into the ground as he shot down the landing Ju 88. The famous fighter ace and admired wing leader “Johnnie” Johnson had this to say about Stevens: “To those who flew with him it seemed as if life was of little account to him, for the risks he took could only have one ending ... We have the fondest memories of him.”

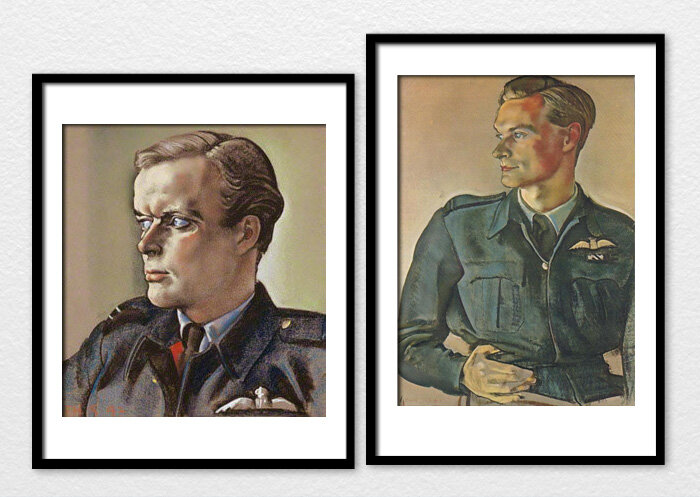

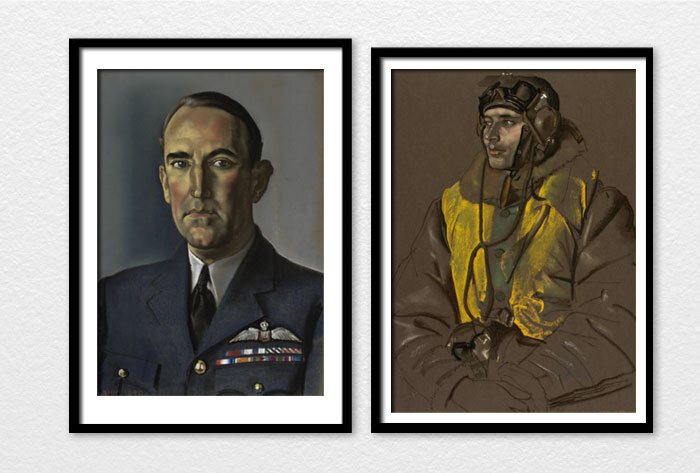

Two of my favourite pastels by Eric Kennington—on the left is Flight Lieutenant Richard Hope Hillary and on the right is Flight Lieutenant Alistair Lennox Taylor, DFC and 2 Bars, MiD

During the war, Hillary became one of the best known pilots of the Battle of Britain, not because he was an ace, but world famous for writing about his experiences and his struggle to overcome burns and wounds suffered in combat. Hillary was born in Australia, but moved to England at age three. He attended Trinity College, Oxford where he excelled as an athlete and joined the university’s air squadron. He was called to service a month after the declaration of war. After flight training, he joined 603 Squadron, flying Spitfires from RAF Dyce and then RAF Hornchurch. After claiming his first victory, he was shot down, crash-landing without injury. On 3 September, the day he became an ace with his fifth confirmed victory, he was himself shot down—in flames. He bailed from his aircraft over the North Sea and was rescued, but horrifically burned about his hands and face. He spent months in hospital and became a patient (known as “Guinea Pigs”) of the groundbreaking plastic surgeon Dr. Archibald McIndoe. During this difficult recovery, he wrote and published The Last Enemy, a book about his life as a fighter pilot and his fight to recover. It was a worldwide literary hit and remains today as one of the most honest and powerful stories of the life of a fighter pilot on squadron during the Battle of Britain. His biographer, Denis Richards wrote “The author was acclaimed not only as a born writer but also representative of the doomed youth of his generation, although in his constant self-analysis he was in fact a most untypical British fighter pilot of 1940.” He regained his flying status despite hands that were crippled and mangled by burns, and went on to train on Bristol Blenheim night fighters. He died along with his navigator while holding over a beacon at night—icing was thought to be the probable cause, but his disfigured hands may have been factors. He was 24 years old. The portrait by Kennington shows him after surgery in 1942, with his eyelids burned away, staring off into a hard light. Kennington and Hillary became friends during this process.

Alistair Taylor was born in Worcester in 1916. He was appointed to a commission in the RAF in November of 1936 and served during the Battle of France with 226 Squadron on the Fairey Battle. Being in a photo reconnaissance squadron, he did not qualify as a Battle of Britain pilot, yet during the period of the Battle, he received two DFCs—one in July 1940 and the other in October. The citation accompanying his second DFC reads: “In September 1940, this officer carried out a successful photographic reconnaissance of the Dortmund-Ems aqueduct. Flying Officer Taylor took off from his base in dense fog but, flying through this, he reached his objective and secured valuable photographs, from a height of 6,000 feet. He has, during the last two months, carried out a number of exceptionally successful reconnaissances, including one over Kiel which was considered the most valuable reconnaissance completed for the Navy during the war.” He received a third DFC the following March. On 14 December 1941, Taylor, then an acting Squadron Leader, disappeared over the North Sea or Norway during an operation. He was just 25.

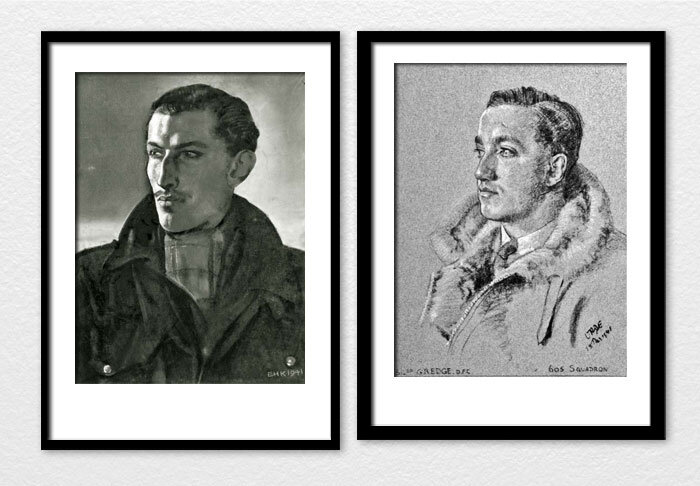

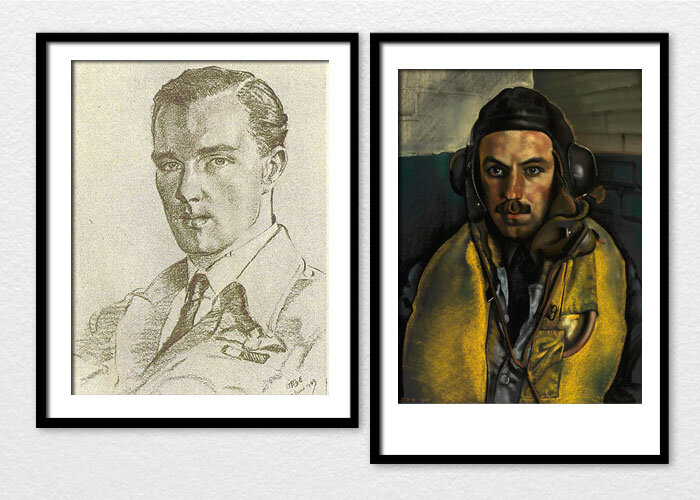

Pilot Officer John “Jack” Urwin-Mann, DSO, DFC and Bar (left) and Flight Lieutenant Phillip Henry “Pip” Barran—sketches by Cuthbert Orde

“Jack” Urwin-Mann was born in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, but was raised in England by British parents. He was claimed as a native by both countries, but it is telling to note that he is listed on the Battle of Britain London Monument as Canadian. As with all the Battle of Britain pilots, he joined before the war, in March of 1939. He was posted to 253 Squadron at RAF Manston in January 1940 and was quickly caught up in the Battle of France. After 253 Squadron was withdrawn having suffered heavy casualties, he was transferred to 238 Squadron at RAF Tangmere. He fought with distinction throughout the Battle of Britain and later in the war. He was awarded his first DFC for his actions in the Battle of Britain, a second one in 1942 and a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in 1943. His personal score at war’s end was nine victories. He survived the war, retiring from the Royal Air Force in 1959 and died of natural causes in 1999.

Flight Lieutenant P.H. “Pip” Barran (Orde spelled his name incorrectly on his drawing) was a Spitfire pilot with 602 City of GlasgowSquadron. He was born in Leeds in 1909. Before the war, he was a manager of a brickworks at a colliery owned by his family. He joined 609 Auxiliary Squadron in 1937 and was made “B” Flight Commander in 1939. He was flying a convoy escort patrol when he was attacked and shot down by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 on 11 July 1940. He successfully bailed out of his burning Spit, landing in the water five miles off Portland Bill, was picked up, but later died of his wounds and burns. He was 32 years old.

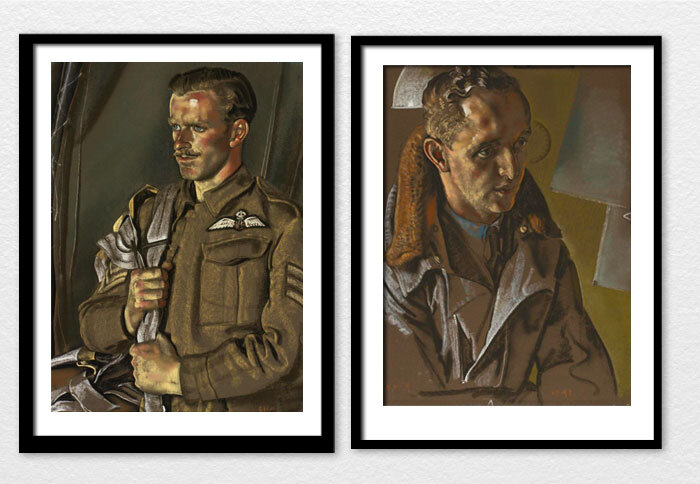

Two of the Canadian Hurricane fighter pilots of 242 Squadron—Flight Lieutenant Stan Turner, DSO, DFC and Bar (left) and Flight Lieutenant Hugh Tamblyn, DFC

Percival Stanley Turner was one of the original 242 pilots who flew in the Battle of France as well as the Battle of Britain under Squadron Leader Fowler Gobeil. Turner holds the record for the most combat ops flown by a Canadian (500). Turner transferred to the RCAF in 1944 and remained in that service after the war. He died in Ottawa in 1983 at the age of 70.

Hugh Norman Donald Tamblyn was born in Watrous, Saskatchewan and joined the RAF in June of 1938. His early flying career was as a Boulton Paul Defiant turret fighter pilot. He then transferred to 242 Canadian Squadron during the Battle of Britain, shooting down 5 enemy aircraft and sharing in the destruction of another. Sadly, Tamblyn, aged 23, was killed in action with 242 Squadron on 3 April 1941. He had radioed that he had been hit by return fire from a Dornier Do 17 and his Hurricane was on fire. A search of the North Sea recovered his uninjured body. He had died of exposure.

Two of the greatest Canadian fighter pilot legends of the Second World War—Squadron Leader Alfred Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie (left, as a Flying Officer, sketch by Cuthbert Orde) and Flying Officer William Lidstone “Willie” McKnight, DFC and Bar (by EricKennington)

Ogilvie was from Ottawa, Ontario, growing up just four blocks from where I am writing this. He joined the RAF in 1939, and made his way quickly through pilot training, arriving on squadron with 609 West Riding Squadron at RAF Middle Wallop, flying Spitfires. He fought admirably through the Battle of Britain, with a score of six victories and was shot down while escorting bombers over France. He managed to bail out, but he was badly wounded. He was captured, spent the next nine months in Belgian hospitals. Upon his recovery, he was sent to Stalag Luft III, where his true legendary status was created. It was here that he became a key member of the escape committee for the Great Escape. He was one of the last of the 76 who managed to escape, and remained at large for two days. He was subsequently captured and interrogated. Fifty of the 73 who were recaptured were murdered by the Gestapo and the SS—shot singly or in pairs (not all at once as Hollywood would have you believe). Ogilvie was one of the lucky ones who was not murdered. He joined the postwar RCAF and flew transport aircraft with 412 Squadron and retired in 1962. He died in 1999 in Ottawa.

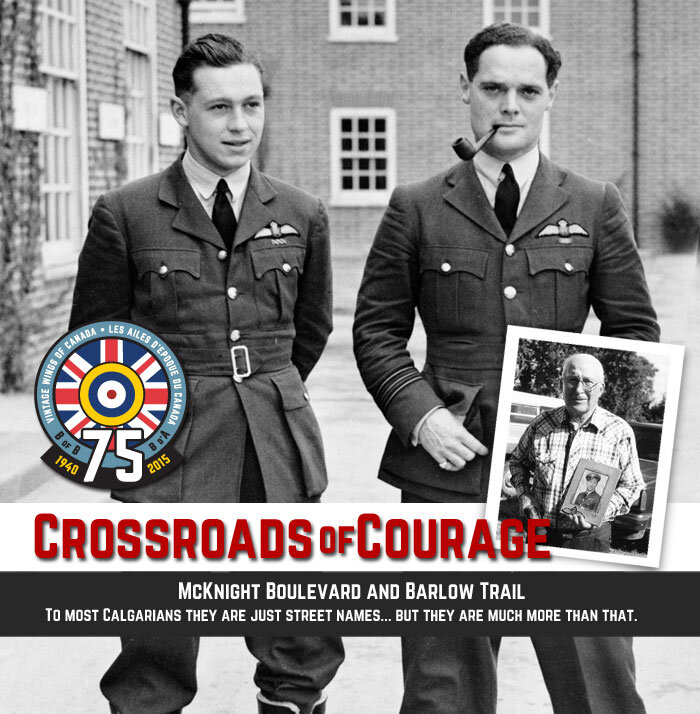

Flying Officer “Willie” McKnight, of Calgary, Alberta is perhaps the most celebrated Canadian of the Battle of Britain. McKnight, jilted by his girlfriend whilst attending medical school at the University of Alberta, quit his studies and travelled to England on his own money to enlist in the Royal Air Force in 1938. McKnight, an enfant terrible with his wild, rebellious ways, cut quite the swath through his squadrons, being confined to barracks on two occasions, held in open arrest as “perpetrator of a riot”. McKnight was credited with 18 victories and was Bader’s preferred wingman. He survived both the Battle of France and Britain, but was shot down over the English Channel in January of 1941. He was the fourth highest scoring Canadian fighter pilot of the Second World War.

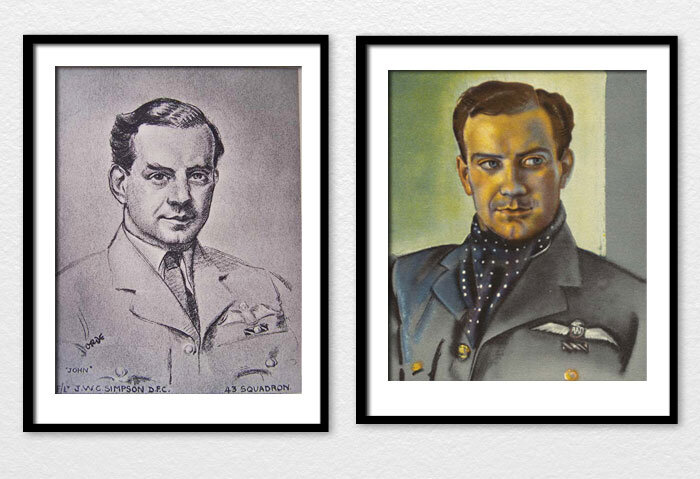

Flight Lieutenant John William Charles Simpson, DFC and Bar, as portrayed by Orde (left) and Kennington (right). The British-born Simpson joined 43 Squadron on Hawker Furies in October 1936, with the war still three years away. His first victory over the Germans was in February 1940. After his 8th victory, he was shot down in July of 1940, surviving with injuries. After recuperation, he rejoined 43 Squadron. In December of 1940, he was given command of 245 Squadron at RAF Aldergrove. By war’s end he had a personal score of 9.5 victories and had achieved the rank of Group Captain. He continued with the RAF after the war until his death by suicide in 1949.

Flight Lieutenant Geoffrey “Sammy” Allard, DFC, DFM and Bar by Cuthbert Orde (left) and Eric Kennington (right). Allard was born in York, England in 1912. He joined the RAF in 1929, at the age of 17, qualifying as a Leading Aircraftman mechanic. But “Sammy” wanted to fly and so he applied to be a pilot and was accepted. He joined 87 Squadron in 1937 as a Sergeant pilot, flying the Gloster Gladiator and then with the newly reformed 85 Squadron at RAF Debden, flying Gladiators at first then the Hawker Hurricane. Allard was a fine fighter pilot and in the Battle of France, he scored at least 8 victories. For his fighting spirit, Allard was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal (the equivalent of a DFC, but for non-commissioned officers). He continued to mount victories through the early months of the Battle of Britain. For his actions, he was commissioned in August and then quickly promoted to Flight Lieutenant and given a flight leader role. Shortly thereafter a Bar to his DFM was gazetted and less than a month later he received the DFC. The squadron was withdrawn from front line service in September, rested and then sent to convert from their Hurricanes to the Douglas A-20 Havoc, getting ready for a night fighter role. On 13 March 1941, Allard and two other pilots took off from RAF Debden in a Havoc. Not long afterwards, their aircraft crashed, killing all three pilots. Investigations into the crash revealed that an unsecured nose panel had come away and lodged in the rudder, jamming it and causing the crash. He had 17 victories to his credit. Allard was 28 years old.

Cuthbert Orde’s sketches of Flight Lieutenant John Dunlop Urie (left) and Sergeant Clifford Whitehead, DFM

Scottish-born John Urie did what any young man from Glasgow with an interest in aviation would do in 1935—he joined the Royal Air Force’s 602 City of Glasgow Auxiliary Squadron—Glasgow’s Own. Serving with 602, he fought through the Battle of Britain, being wounded trying to land his heavily damaged Spitfire. He was promoted to Squadron Leader, taught at an operational training unit and then, as a Wing Commander, he led 151 Wing in Russia. He died in 1999.

Flight Sergeant Charles Whitehead joined the RAF in 1931 at the age of 17, and like a number of future fighter pilots in the RAF, started as an aircraft rigger. He applied for pilot training and by the time the Second World War had started he was a seasoned pilot. He few with 56 Squadron at RAF North Weald and later flew operations in both the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, becoming an ace in the process and once bailing out of a stricken Hurricane. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal and was gazetted at the end of August at the height of the Battle of Britain. In January of 1941, Whitehead was commissioned as a Flying Officer Instructor and taught at No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School at Brough. Sadly, he was killed in a flying accident with a Tiger Moth. He was 27 years old.

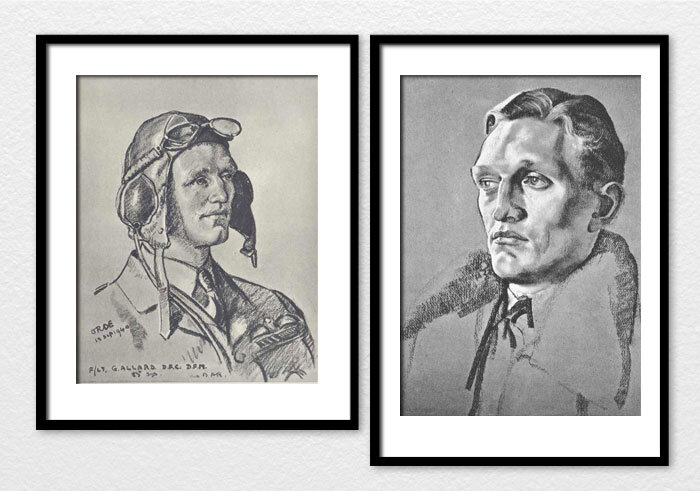

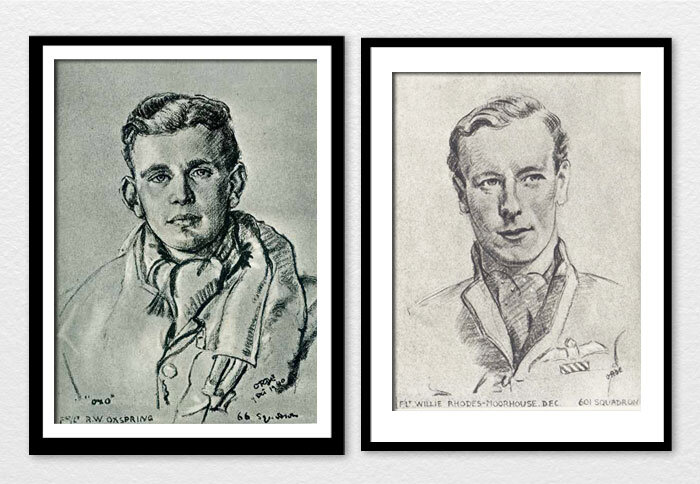

Like Father, Like Son. Flight Lieutenant Robert Wardlow Oxspring, DFC and Two Bars, AFC (left) and Flight Lieutenant William Henry Rhodes-Moorhouse, DFC by Cuthbert Orde

Both of these men were the sons of First World War fighter pilots and heroes. “Bobby” Oxspring was born in 1919, the son of Robert Oxspring, a founding member and commander of 66 Squadron and a triple ace in the Great War with 16 victories. The younger Oxspring wanted to follow in his father’s prop wash, and was granted a probationary commission as a Pilot Officer in 1938. He nearly equalled his father’s score at 13.5 victories and his first squadron assignment was with 66 Squadron, his father’s old unit. He fought in the Battle of Britain, in North Africa and in Europe and was shot down twice and survived. He won three DFCs, an Air Force Cross and the Dutch Airman’s Cross. Oxspring remained in the RAF after the war and led a flight of 54 Squadron de Havilland Vampires across the Atlantic (via Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland) to Canada and the United States—the first jet aircraft to cross that ocean. “Bobby“ Oxspring died at the age of 70 in 1989.

“Willie” Rhodes-Moorhouse, born in 1914, was the son of William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse, VC. The elder Moorhouse was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross the year after young Willie’s birth—for pressing home an attack on a railway junction and despite being seriously wounded, getting his aircraft back to base and making his report to his unit before getting his wounds taken care of. He died the next day. So, “Willie” had some big shoes to fill, and he did his best. He grew up in a privileged and wealthy family, being educated at Eton (where, at the age of 17 he got his pilot’s license.) He inherited his family fortune in 1933 and spent the next few years travelling broadly. Despite his wealth and privilege, he joined the RAF in 1937 flying Bristol Blenheims with 601 County of London Squadron. He flew bombing missions against Germany in the opening months of the war, and when 601 Squadron re-equipped with the Hawker Hurricane, he participated in the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, with 6 victories to his credit. At the height of the Battle of Britain, Rhodes-Moorhouse was shot down and killed over Tunbridge Wells. His Hurricane dove vertically into the ground. The RAF felt the wreck was too deep and difficult to recover, but his family paid to have his body recovered and he was cremated. Two generations of fighter pilots who died in combat in two world wars—a heavy family price to pay.

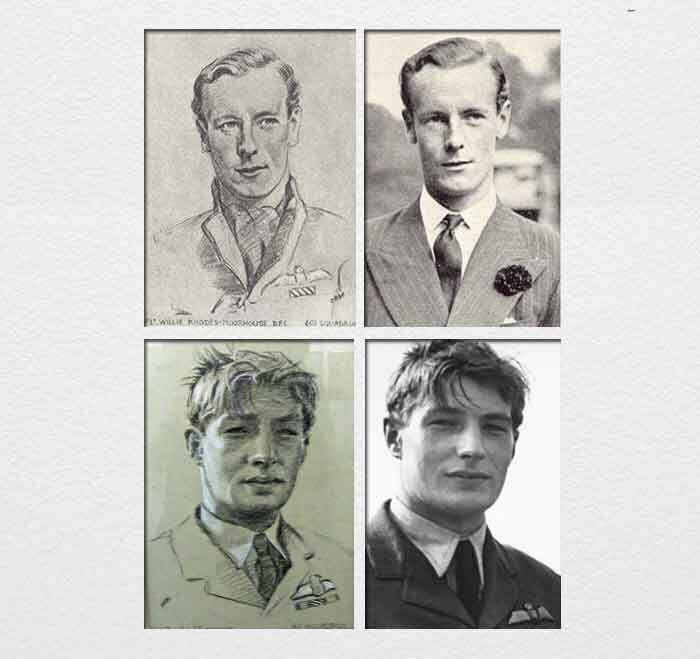

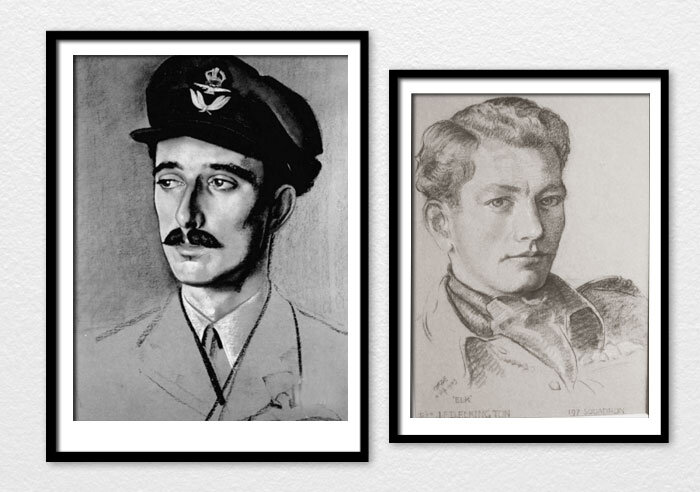

It appears that not all of Orde’s pastel or charcoal sketches were done with the living honouree present. Looking at these two portraits, it is clear to me that they were drawn from the paired photographs—“Willie” Rhodes-Moorhouse, DFC (top) and Flight Lieutenant Richard Hugh Anthony “Dickie” Lee, DSO, DFC, MiD. The one thing that these two have in common is that they were both killed in combat in August during the Battle of Britain. It was the Royal Air Force which selected or recommended subjects for Orde’s portraits, and in the case or these two men, there was only photographs to work with by the time Orde was sketching. Photos: Battle of Britain London Memorial

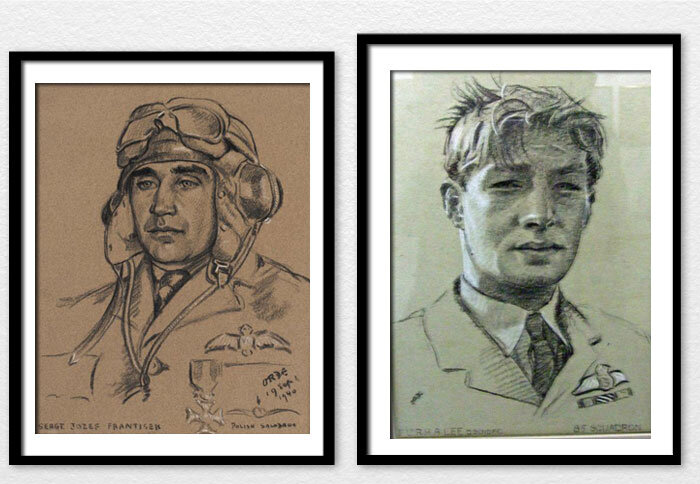

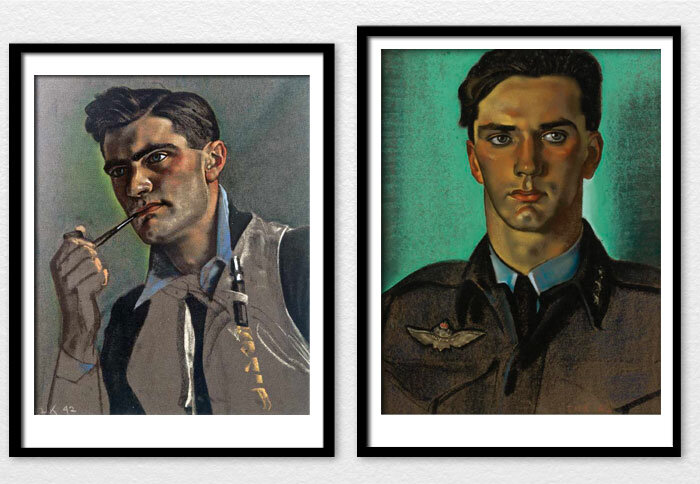

Sergeant Josef Frantisek, DFM and Bar (left) and Richard Hugh Anthony “Dickie” Lee, DSO, DFC, MiD—both by Cuthbert Orde

Though Czechoslovakian by birth, Frantisek was an extremely successful member of the Polish 303 Kosciuszko Squadron of the RAF. He joined the Czechoslovak Air Force in 1934, but following the German occupation of his homeland, he escaped to Poland and joined that air force for the fight against the Nazis when Poland was invaded. He attacked German ground troops in an unarmed training aircraft, throwing grenades from his cockpit. Escaping with Polish aircraft to Romania, he was interned, but managed to escape to North Africa and then to France where he is thought to have fought with the French. Following the fall of France, he evacuated to England, was retrained and assigned to 303 Squadron on Hurricanes. He was a spectacularly undisciplined fighter pilot... but an extraordinarily successful one. Despite constant breaking of formation to hunt on his own and the anger of his commanders, he managed to shoot down 17 (possibly 18) German aircraft (9 fighters) in a period of 28 days. He was killed in early October in an accident returning to the squadron base at RAF Northolt after a patrol. In addition to his DFM, Frantisek was awarded medals from both France (Croix de Guerre) and Poland (Cross of Valour—3 times). He was buried in the Polish Air Force cemetery at Northwood. Born Czech, eternally Polish.

“Dickie” Lee was born in London in 1917. After his public schooling at Charterhouse, he entered the RAF College at Cranwell at eighteen years of age. Following flight training, he was posted to 85 Squadron at RAF Debden and was deployed to France following the outbreak of the war. He accounted for 85 Squadron’s first victory, shooting down a Heinkel He 111 in November 1939. He was awarded the DFC, being gazetted in March of 1940. In May, he shot down another, but was then shot down himself. He was at first captured, but managed an escape, returning to his squadron. He and his squadron were recalled to England and he then joined 56 Squadron. Over Dunkirk, he was shot down again, being rescued from the sea. He was awarded the DSO afterwards. August 1940 found him back with 85 Squadron and on the 18th, he was sent to pursue an enemy formation 30 miles off the coast. He never returned. He was 23 years old.

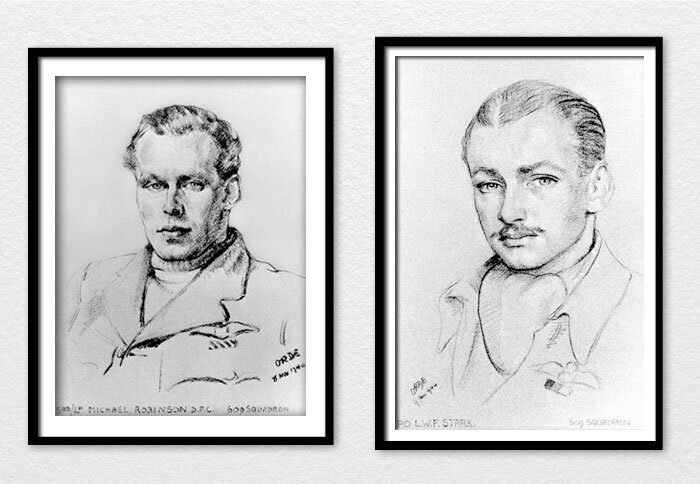

Two pilots and commanders of 609 West Riding Squadron as sketched by Cuthbert Orde—Squadron Leader Michael Lister Robinson, DSO, DFC (left) and Pilot Officer Lawrence William Fraser “Pinkie” Stark, DFC and Bar, AFC

Robinson was born in Chelsea, England in 1917, the son of an aristocrat. He joined the RAF in 1935 on a short service commission in September of 1935 and joined 111 Squadron at RAF Northolt a year later, flying the Bristol Bulldog and Gloster Gauntlet. 111 Squadron would become the first operational Hawker Hurricane squadron of the Royal Air Force. He flew Hurricanes in the Battle of France with 87 Squadron of the British Expeditionary Force, but was injured in a crash of the unit’s Miles Master. Upon recovery, he was posted to 601 County of London Squadron at RAF Tangmere. Six weeks later, having achieved ace status, he moved briefly to 238 Squadron, before taking command of 609 Squadron at RAF Middle Wallop in early October of 1940. He was awarded the DFC by the end of November, the DSO in August 1941 followed by the Belgian Croix de Guerre. By the end of August 1941, he was leading the Biggin Hill wing. After a short rest and assignment as aide to the Inspector General of the RAF, he returned in January 1942 to lead the wing at RAF Tangmere. Leading his wing, he failed to return from a fighter sweep in April of 1942.

Stark was not in the Battle of Britain. He travelled across the Atlantic for pilot training in Canada with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. After getting his wings, he remained in Canada as a staff pilot at a Bombing and Gunnery School. He joined 609 Squadron in January of 1943, flying Typhoons and becoming an ace on the type—a difficult thing to achieve given the close air support role of the Hawker Typhoon. He was shot down by anti-aircraft fire in 1944, but evaded capture and got back to his unit in England. He commanded 609 Squadron in the final months of the war. Postwar, Stark flew de Havilland Vampires in the Middle East, and spent two years in Canada with the Cold Weather Test Unit of the RAF. He died in 2004 in England.

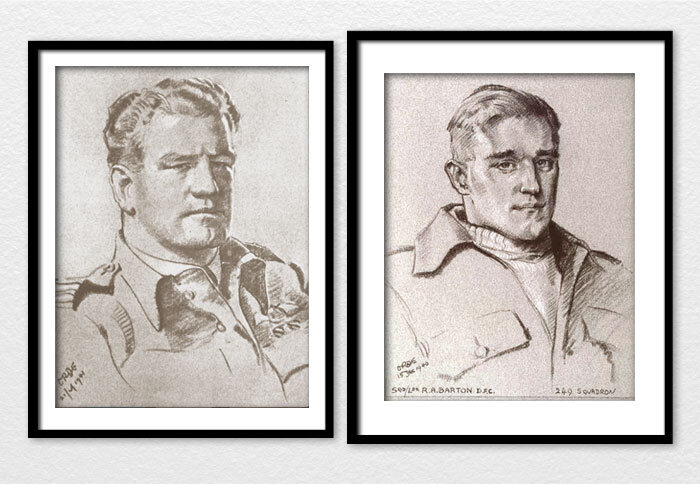

Two steel-jawed legends of the Battle of Britain from the colonies, drawn by Cuthbert Orde—Flight Lieutenant Alan Christopher “Al” Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC and Bar (left) from Auckland, New Zealand and Squadron Leader Robert Alexander “Butch” Barton, OBE, DFC and Bar, MiD of Kamloops, British Columbia

By war’s end, Air Commodore “Al” Deere had earned a reputation as one of the RAF’s fiercest fighter pilots, a pugilist of the skies. He joined the Royal Air Force after training in New Zealand. His first operational fighter unit was 74 Squadron, but he quickly moved on to 54 Squadron, flying Gloster Gladiators. As the war heated up, he transitioned to Spitfires and was involved in the Battles of France and Britain. The citation accompanying his second DFC says all there is to know about “Al” Deere: “Since the outbreak of war this officer has personally destroyed eleven, and probably one other, enemy aircraft, and assisted in the destruction of two more. In addition to the skill and gallantry he has shown in leading his flight, and in many instances his squadron, Flight Lieutenant Deere has displayed conspicuous bravery and determination in pressing home his attacks against superior numbers of enemy aircraft, often pursuing them across the Channel in order to shoot them down. As a leader he shows outstanding dash and determination.” London Gazette—6 September 1940. “Al” Deere’s accomplishments are too numerous to tell in this caption, but two facts tell you a lot about the man and his war experience. First, he was selected to lead fellow Battle of Britain fighter pilots in the funeral cortege for Winston Churchill and secondly, after his death in 1995 at age 77, his ashes were scattered over the River Thames in London by a Spitfire of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

“Butch” Barton joined the Royal Air Force at age 19, travelling to England to take a short service commission. He started his career before the war on biplane fighters with 41 Squadron. With the outbreak of the war, Barton joined 249 Squadron flying Hurricanes at RAF Boscombe Down. He became a flight commander with 249 during the Battle of Britain, once bailing from his Hurricane after it was hit from return fire from a Dornier Do 17 bomber. By the end of the Battle of Britain, he was awarded a DFC for his “outstanding leadership”. With 249 Squadron, he also took part on the air war over Malta, adding to the total of his victories. Under Barton’s leadership, 249 Squadron became one of the most respected and lethal units on Malta and in the RAF. By war’s end he was a Wing Commander with 14 victories to his credit. The Battle of Britain London Monument web page says this about Barton: “During his career he had always tried to maintain the highest standards of chivalry, once severely reprimanding an inexperienced colleague who had finished off a damaged German aircraft, killing the pilot as he was attempting to crash-land over England... “Butch” Barton died on 2nd September 2010. His ashes were scattered on his favourite lake in British Columbia on the morning of 15th September, Battle of Britain Day.”

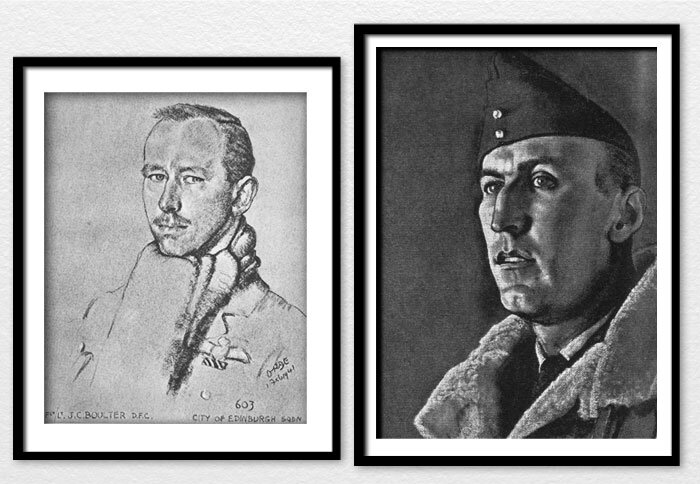

Cuthbert Orde’s rather wary-looking interpretation of Flight Lieutenant John Clifford Boulter, DFC (left) and Kennington’s dramatic portrait of a young Air Vice Marshal David Francis Atcherley, CB, CBE, DSO, DFC when he was likely a Group Captain or Squadron Leader.

Boulter was born near London, England in 1912. He was granted a short service commission with the RAF in 1936. By October of that year, he was posted to No. 1 Squadron at RAF Tangmere flying the mighty Hawker Fury, one of the last biplane fighters of the RAF. This was followed by a turn with 72 Squadron at RAF Church Fenton flying the Gloster Gladiator. In September of 1939 he joined 603 Squadron at RAF Turnhouse, flying the Supermarine Spitfire. During the “Phoney War” he did get a crack at the enemy, damaging a Heinkel He 111. In March, as the war heated up in Western Europe, a taxiing accident put him in the hospital. By August he was back in the thick of things, becoming an ace and receiving a DFC for his efforts. In February of 1941, he was involved in an accident at RAF Drem. His Spitfire was struck by a landing Hurricane as he was readying for takeoff and he died later of his injuries. He was 28 years old.

David Atcherley was older than most pilots by the outset of the war. He was born in January of 1904, attended Sandhurst Military Academy in 1922, having been rejected by the RAF for health reasons. As an army officer with the East Lancashire Regiment, he was seconded to the RAF in 1927, where he learned to fly despite not being in the RAF. His flying and leadership skills were such that the RAF converted his secondment into a permanent commission in 1929. By the start of the war, he was commanding 85 Squadron, flying Hawker Hurricanes and then he took command of 253 Squadron. He found greatest success as a night fighter commander with 25 Squadron flying Bristol Beaufighters. The citation attached to his DFC reads: “This officer has carried out a large amount of operational flying at night, sometimes in adverse weather conditions. The efficiency of his squadron and the success it has had is due to Wing Commander Atcherley’s drive, energy and leadership. He has destroyed three enemy aircraft at night.” He fractured his neck in the summer of 1941 in a crash on takeoff, but this did not stop him. With the help of 6 ground crew, he was helped into the cockpit of his “Beau” for each operation and continued to fight. He took his success with night fighters to the Tunisian Campaign, in charge of all operations in 1943. He rose quickly up the command ladder during and after the war. He disappeared in June of 1952 while piloting a Meteor jet fighter on a short trip from Egypt to Cyprus. He was never found.

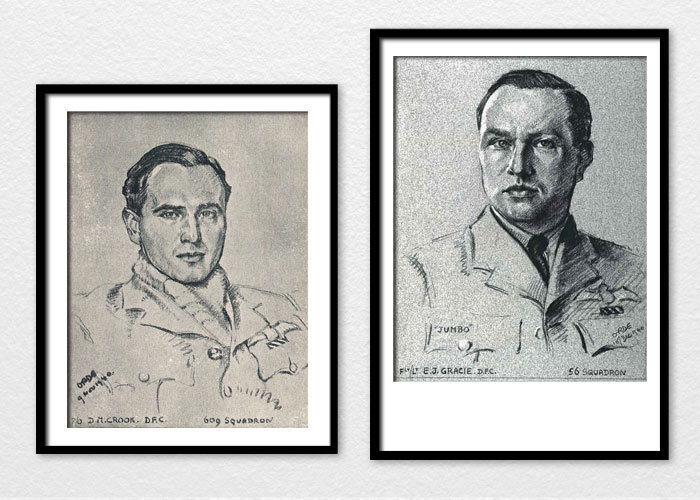

Two Battle of Britain portraits by Cuthbert Orde—Pilot Officer David Moore Crook, DFC and Flight Lieutenant (later Wing Commander) Edward John “Jumbo” Gracie, DFC

Crook was born in West Yorkshire in 1914 and attended Cambridge University. With the possibility of war becoming more certain every day, he joined the Royal Auxiliary Air Force with 609 Squadron and began his flying training. A week before the declaration of war, he was called to full-time service. He then began his advanced flying training on Spitfires and was ready for combat at the end of the Battle of France. By the end of September he was an ace and was awarded a DFC in November. In April, Crook went to a flying instructor’s course and then on to the Elementary Flying Training School at RAF Carlisle, where he taught flying for the next three years. Wanting to get back to combat, he was reassigned to Operational Training Units at 41 OTU and 8 OTU, possibly for training in Photo Reconnaissance as both OTUs trained PR Spitfire pilots. On 18 December 1944, he lost control of his Spitfire at 20,000 feet and dove straight into the sea near Aberdeen, Scotland. He was never found, but the likely cause was a malfunction of his oxygen system, causing him to lose consciousness.

“Jumbo” Gracie was born in 1911 in Acton, England and joined the RAF on a short service commission at the age of 19. He left the RAF for a short period (a dismissal following a court martial), then rejoined in 1937 and was called up in 1939 at the outset of the war. Following his training on Hurricanes, he was posted to 79 Squadron in early 1940 and then, as a flight commander, to 56 Squadron at the beginning of the Battle of Britain. He was an ace by the end of August. At that time, he himself was shot down in his Hurricane, breaking his neck in the process. He was awarded the DFC in October and then rejoined 56 Squadron until rested in January of 1941. In March of 1941, he was given command of 23 Squadron for a brief period before moving to 601 Squadron—at that time the only P-39 Bell Airacobra-equipped unit in the Royal Air Force. These aircraft never saw combat however. He left that unit in December, converted to Spitfires and in March of 1942 was leading a flight of Spits flying off of the Royal Navy carrier HMSEagle for delivery to the embattled island of Malta. Following their safe delivery, he took over command of 126 Squadron on Malta, flying the very aircraft he delivered. He was later flown back to England to lead 601 (finally rid of the Airacobras) and 603 Squadron from the deck of USS Wasp for a similar delivery to Malta. Once back on the island, he was made Wing Commander, commanding RAF Takali and proved to be a courageous and much-admired leader for his coolness under attack. By mid-summer 1942, he was sent back to England, briefly in command of 32 Squadron. After transition to de Havilland Mosquitos, he joined 169 Squadron. In February of 1944, he failed to return after an attack on Germany. At the time, he was 32 years old.

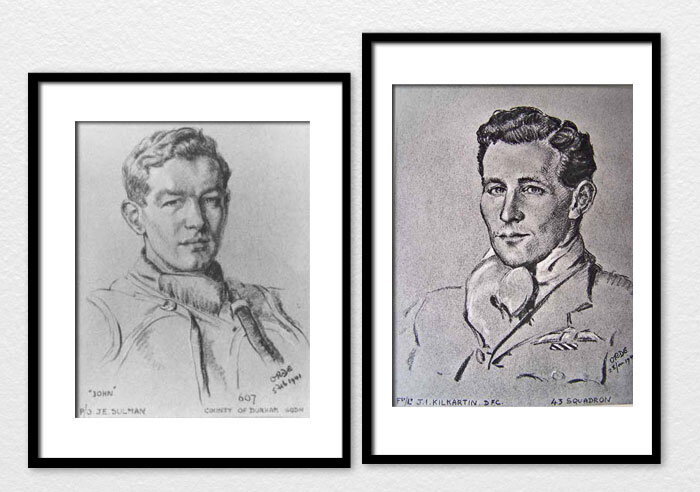

ilot Officer John Edward Sulman (left) and Flight Lieutenant John Ignatius “Killy” Kilmartin, OBE, DFC, by Cuthbert Orde

Pilot Officer Sulman was born in Hertfordshire, England in 1916 and joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve as a Sergeant pilot. At the outbreak of the war, he was sent for flying training and joined 607 County of Durham Squadron in June 1940, flying the Hawker Hurricane. He took part in the Battle of Britain, claiming one aircraft shot down. Following the Battle, he was reposted as a flying instructor, before rejoining 607, participating in ground attacks in France. In November of 1941, he was assigned to the Desert Air Force in North Africa, joining 238 Squadron and flying Spitfires. He was killed in action a few short weeks later in March 1942—somewhere over Cyrenaica on the Libyan coast. He was an example of the typical line pilot who did his duty with courage and dependability, giving his life for his country and comrades, with little in the way of recognition. But he did have his portrait done by Orde and perhaps that is his lasting legacy.

Despite the animosity most Republican Irishmen felt for the British, there were many who fought alongside them in the Second World War, and ten who fought in the Battle of Britain. John Kilmartin was born in 1913 in Dundalk, Ireland near the border with Northern Ireland. His father died when he was nine and he was shipped to Australia as part of a scheme to resettle poor and disadvantaged children. One can only imagine how he felt as he sailed to Australia where he worked on a cattle farm and later, in Shanghai, as a bank clerk and part-time jockey. He joined the RAF in 1937 and after training, was posted to 43 Squadron at RAF Tangmere in January 1938. With the war declared, he was posted to No. 1 Squadron and sent to France. During the Battle of France, flying Hawker Hurricanes, he quickly built up a score and was a double ace by the middle of May. The spent pilots of No. 1 Squadron were withdrawn to England at the end of May and “Killy” was sent to train others for the coming Battle of Britain. He rejoined 43 Squadron at the beginning of September 1940, increasing his score during the Battle of Britain. He was awarded a DFC and gazetted on 8 October. In the spring of the following year, he was sent to command 602 Squadron, but that was short-lived. Instead, he went to West Africa, taking command of 128 Squadron in Sierra Leone to defend that country in the event that the Vichy French attacked from their bases in Dakar, Senegal to the north. He returned to Great Britain in August of 1942 to command 504 Squadron on Spitfires and then eventually the whole wing at RAF Hornchurch. In 1944, Kilmartin led the Typhoon wing of the Tactical Air Force. He was made an OBE in January 1945, went on to serve in Burma on P-47 Thunderbolts and then to Sumatra. The breadth of his war service spanned 6 years of the war and three continents. He remained in the RAF after the war, and held staff positions at NATO. He died in 1998.

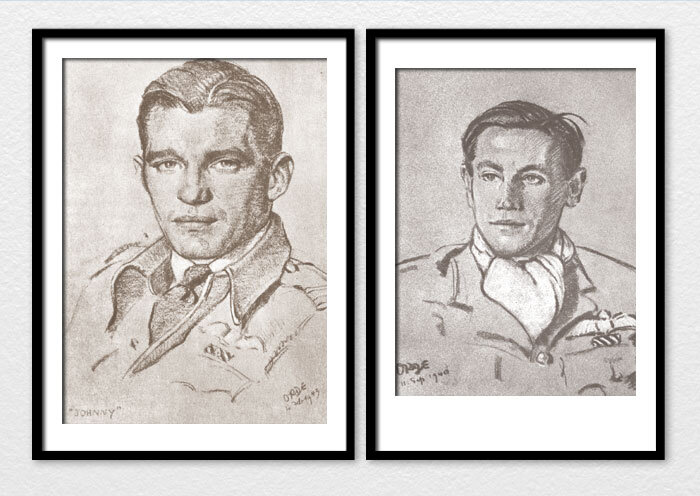

Cuthbert Orde likely met more of the great fighter pilots of the Second World War than any person of the period. He was able to spend time with some of the most compelling, dutiful, courageous and accomplished men of the war. Case in point… the future Air Vice Marshal James Edgar “Johnnie” Johnson, CB, CBE, DSO and Two Bars, DFC and Bar (left) and the future Air Vice Marshal Harold Arthur Cooper “Birdie” Bird-Wilson, CBE, DSO, DFC and Bar, AFC and Bar

Nearly every portrait that Orde sketched had an inscription with the pilot’s rank, initials, name and sometimes awards. In the case of “Johnnie” Johnson, Orde merely wrote the name “Johnny” (sic) in quotation marks—such was his stature at the time the portrait was done in 1943. Johnson was born in Barrow upon Soar, England in 1915. He was an avid sportsman and hunter, skills that he later attributed to his success as a fighter pilot. He graduated from University of Nottingham as a civil engineer. With a lifelong interest in aviation, he began paying for flying lessons and attempted to enroll in the Auxiliary Air Force, but was rejected because his social standing was not of the required elevation. But as war loomed, the RAF did away with some of its earlier restrictions. He applied for the RAF again and was rejected a second and third time—on the grounds there were too many applicants and that he had a rugby injury that caused chronic issues. Finally in 1939, he was accepted for flying training. Throughout his training, his rugby injury, a broken and badly healed collarbone, caused him great difficulty, but he managed to qualify as a Spitfire pilot in August of 1940. His spectacular fighter pilot career started with a single op with 616 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, but his painful injury soon had him in hospital for corrective surgery. By the beginning of 1941, he was back with 616. By the time the war had ended, he was Great Britain’s highest scoring ace with at least 37 victories—all which were against fighters except for his first (a Dornier Do 17). “Johnnie” Johnson became the much-loved Wing Commander of 127 Wing, RCAF at RAF Kenley in 1943 taking the three Canadian squadrons of his wing all the way to VE-Day with outstanding success. Shortly after his arrival at 127 Wing, Squadron Leader Syd Ford of 403 Squadron laid a pair of blue “CANADIAN” shoulder flashes on his desk and said “The boys would like you to wear these. After all, we’re a Canadian wing and we’ve got to convert you. Better start now.” “Johnnie” died in England in 2001 at the age of 85.

“Birdie” Bird-Wilson was born in Wales in 1915 to parents who, as tea plantation managers, lived most of their lives in Bengal, India. Bird-Wilson remained in Great Britain for all of his formative life. In November of 1937, he took a short service commission with the RAF, joining 17 Squadron on Gloster Gauntlets following flight training. A few months before the start of the Second World War, the squadron re-equipped with the Hawker Hurricane. Not long after his Hurricane transition, he crashed while flying a British Aircraft Swallow liaison aircraft in bad weather. His passenger was killed, and he survived, but had severe facial injuries including the loss of his nose. After multiple surgeries under the skilled and sympathetic hand of Dr. Archibald McIndoe, he received a new nose and a new lease on life. He returned to flying status in December of 1939 and rejoined 17 Squadron at the end of February 1940. He deployed to France twice during the Battle of France and fought as well through early months of the Battle of Britain, receiving the DFC. He was shot down on 24 September 1940 by no less than Luftwaffe legend Adolph Galland (the German’s 40th victory) and bailed out into the North Sea near Chatham. After recovering from his injuries, he returned briefly to his squadron before being assigned an OTU instructing job. In March 1941, he returned to an operational role with 234 Squadron at RAF Warmwell. Following another OTU assignment, he was given command of his own squadron—152 Squadron—at RAF Eglinton, then 66 Squadron. By 1943, he was Wing Leader with 122 Wing and the recipient of a second DFC. Throughout the rest of the war he took staff training in the UK and America and ended the war in command of a Meteor jet conversion unit at RAF Colerne and was awarded a DSO for his fine leadership. He rose in prominence in the RAF after the war, retiring in 1974 as an Air Vice Marshal and went to work in the aerospace industry. He died in 2000, three days before the end of the millennium.

Flight Lieutenant (later Wing Commander) Thomas Francis “Ginger” Neil, DFC, AFC (left) and Pilot Officer (later Flying Officer)Malcolm Ravenhill

It wasn’t a given, but both Orde and Kennington seemed to prefer to paint their subjects gazing out to their right, perhaps to take advantage of the light in his studio. “Ginger” Neil was born in 1920 and at the age of 18, joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in October 1938. He began his flight training in 1939 and was called up within 24 hours of the start of the Second World War. When his fighter training was complete in the middle of May 1940, he was posted to 249 Gold Coast Squadron at RAF Church Fenton and then RAF North Weald. He shot his first enemy aircraft down at the beginning of September and by the end of that single month, he was an ace with seven confirmed victories. By the beginning of November, he was a double ace, having shot down three on 7 November. In that month, he collided with another Hurricane (piloted by Wing Commander F.V. Beamish—his story follows) and was forced to bail out. He was awarded the DFC in October and a Bar to this award in November. He left for Malta with 249 Squadron, flying their Hurricanes from HMS Ark Royal in May 1941. He returned to the UK in March of 1942 and went to a Spitfire OTU and then on to command 41 Squadron at RAF Llanbedr on the coast of Wales. In the summer of 1943, he was posted as an instructor at 53 OTU and from there to the United States Army Air Force as a liaison officer. He retired from the Royal Air Force in 1964 as a Wing Commander.

Flying Officer Malcolm Ravenhill was born in the industrial town of Sheffield, joining the RAF on a short service commission in March of 1938. He took his flying training at Abu Sueir, Egypt and, upon returning to England and converting to Hurricanes, he joined 229 Squadron at RAF Digby in March of 1940. On 1 September 1940, he was shot down over RAF Biggin Hill and was hospitalized with shock. After recuperating, he returned to the Battle of Britain and by the end of September was shot down and killed when his Hurricane crashed at Ightham. He was 27 years old.

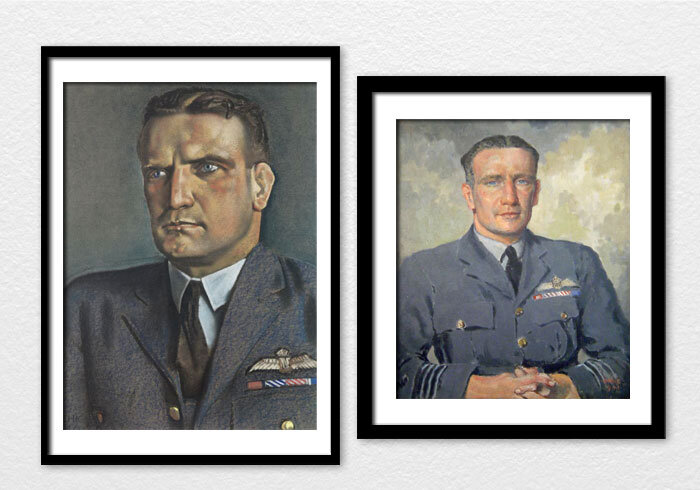

Two paintings of the same man—one by Kennington (left) and the other by Orde. Though most of his portraits were done in charcoal and white chalk, Cuthbert Orde also completed numerous oil paintings of Royal Air Force officers. Group Captain Francis Victor Beamish, DSO and Bar, DFC, AFC was born in County Cork in 1903, well before the births of most of the pilots of the Battle of Britain. As such, he felt the full impact of the First World War on families in Great Britain. He was one of three brothers who went on to outstanding careers in the RAF. His brother George, a gifted professional rugby player would attain the rank of Air Marshal and his brother Charles, also a rugby player, would become a Group Captain. Beamish attended the RAF College at Cranwell in 1921 and upon graduation, he joined No. 4 Army Cooperation Squadron at RAF Farnborough, flying the Bristol Fighter. After a period as an instructor at Cranwell, he was exchanged for an RCAF officer and spent two years in Canada before returning to lead a flight in 25 Squadron. He came down with tuberculosis in 1933 and was retired from active service with the air force. RAF to the bone, Beamish was decidedly unhappy about his forced retirement and took up a series of civilian positions with the RAF Volunteer Reserve. He recovered his health fully by the beginning of 1937 and was reinstated as a flying Flight Lieutenant. He began his “comeback” in command of the new Meteorological Flight at RAF Aldergrove (for which he was awarded the Air Force Cross) and finally he rejoined a combat-ready squadron when he took command of 64 Squadron at RAF Church Fenton at the end of 1937. At the outset of the Second World War, at the ripe old age of 36, he took command of 305 Squadron. Though he was a very good squadron commander and aggressive pilot, he also had recognized staff and administration skills, and he then returned to Canada for staff duties which included an assessment of the Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk fighter. He returned by the end of May, 1940 to take command of the wing at RAF North Weald. He flew operational sorties with his squadrons whenever possible and began to rack up victories against the Germans in the Battle of Britain. In July he was awarded the DFC and in November the DSO. As mentioned on the previous caption, he was involved in an air-to-air collision with “Ginger” Neil, necessitating a forced landing. He was damaged three times in combat and safely landed his Hurricane each time. He was then assigned command of the wing at RAF Kenley and, in February of 1942 while on patrol, spotted the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen along with defensive ships making their famous, and ultimately successful, Channel Dash to safety in Wilhelmshaven. Two months later, he was killed in action while engaging the enemy near Calais. He was 38 years old.

Kennington’s portrait of Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Alan Donald Frank, CB, CBE, DSO, DFC (left) is one of my very favourites of Kennington’s works. There is something about the pensive Frank in this portrait that exudes the innocence, shyness and determination of youth. It speaks to all the young men who joined the RAF as the war spread westward towards Great Britain. His blue eyes are filled with the strength of purpose that would be needed to fight the Nazi threat during the next six years. It also reminds me that even aging Air Vice Marshals about to retire from the Royal Air Force were, at one time, fresh and new and open hearted. He was born in Cheshire in 1917 and joined the RAF at the end of 1936 and after flight training, joined 150 Squadron flying the Fairey Battle. He accompanied his squadron to France, where they were part of the Advanced Air Striking Force. The squadron, flying the obsolete Battle, suffered heavy losses and was withdrawn from France in May of 1940 to re-equip with the twin-engine Vickers Wellington medium bomber. In late 1941, after being awarded a DFC, he moved to 460 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force, which was just then forming at RAF Molesworth, flying the Wellington. In 1942, following operations with 150 Squadron, he was sent to Georgia as a liaison officer with the British flying training program in America. On his return in 1942, he became a flight commander with 10 Squadron on Handley Page Halifaxes. In April 1943, at the age of 26, he was given command of a Halifax-equipped Bomber Command unit—No. 51 Squadron—at RAF Snaith after which he was awarded the DSO. During this time, he participated in many raids over Germany and Italy, including Operation GOMORRAH, the incendiary raid against Hamburg which resulted in a fire storm that destroyed much of the city. As the war was winding down, he found himself on the air staff ofTiger Force, the Bomber Command plan to send Avro Lancasters and Lincolns with their crews to fight the Japanese after the surrender of Germany. After the war, Frank went on to a stellar operational career including forming and leading 83 Squadron, the first Avro Vulcan-equipped nuclear strike squadron of the RAF. He commanded a wing of Handley Page Victor nuclear bombers, and ended his RAF career as an Air Vice Marshal, and as Senior Air Staff Officer at Headquarters, Air Support Command of the Royal Air Force.

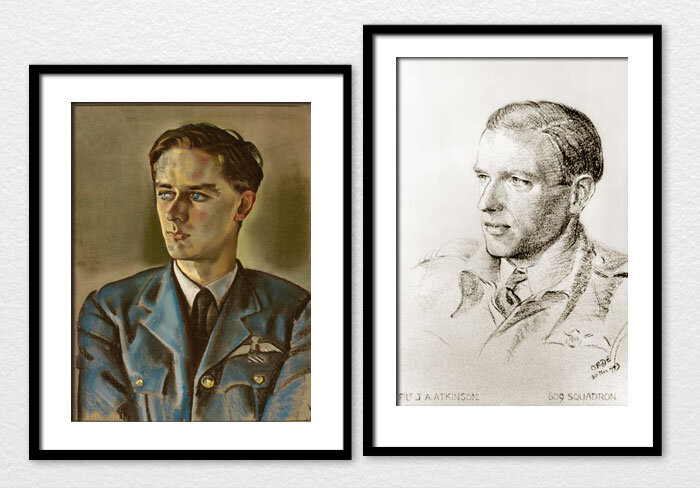

Flight Lieutenant John Joseph “Joe” Atkinson, KCB, DFC joined the RAF from the Oxford University Air Squadron in 1938 and completed his pilot training in England. His first operational posting was in 1940 to 234 Squadron at RAF St Eval, Cornwall, flying Supermarine Spitfires—a very appropriate aircraft for a squadron with the motto “Ignem mortemque despuimus—We Spit Fire and Death.” Later, he moved on to 609 Squadron at RAF Warwell, Dorchester. In 1942, he converted to Typhoons with 609 Squadron at RAF Duxford, and from there to Biggin Hill and Manston, launching fighter operations over France. When his tour of operations ended in 1943 he was awarded the DFC and went on to become a Flying Instructor until the war was over. Released from the RAF in 1945, he went on to have a successful career in the civil service, and was knighted in 1979.

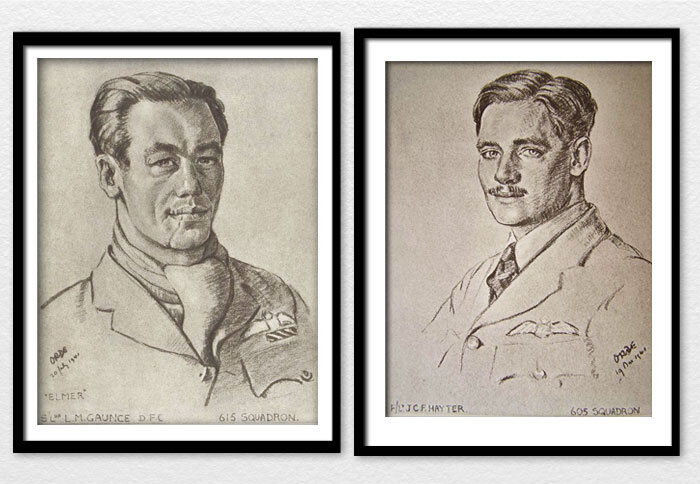

Cuthbert Orde’s portraits of two men from opposite sides of the Earth who came to fight in the defence of Great Britain: Canadian Squadron Leader Lionel Manley “Elmer” Gaunce, DFC (left) and New Zealander Flight Lieutenant James Chilton Francis “Spud” Hayter, DFC and Bar, MiD. After Great Britain and Poland, who were in fact fighting for their futures, New Zealand and Canada were the countries that supplied the most pilots during the Battle of Britain.

Gaunce came from the wide open Canadian Prairies at Lethbridge, Alberta near the Montana border, but was educated in Edmonton. He started out in the Loyal Edmonton Regiment of the Canadian Army, but soon applied for a short service commission with the Royal Air Force. He was accepted in 1936 and embarked for England and flight training. His first squadron was No. 3 at RAF Kenley. Here he flew the Bristol Bulldog, Gloster Gladiator and then the Hawker Hurricane. Gaunce was appointed a Flight Commander with 615 Churchill’s Own Squadron in France, flying the Gloster Gladiator. As the Germans invaded France, Gaunce and 615 were recalled to England for Hurricane conversion. During the Battle of Britain, he was shot down on 18 August, suffering slight burns. At this time he was awarded a DFC for “excellent coolness and leadership” among other things. He rejoined his squadron in a few days, but was again shot down in flames on 26 August. He was rescued from the sea, but sent to hospital suffering from shock. At the end of October, having recovered, he was given command of 46 Squadron at RAF Stapleford Tawney where he fought a rare Italian force attacking Great Britain, shooting down a Fiat CR20 fighter. He left 46 Squadron in December due to ill health, and upon his return to operational status, took over 41 Squadron at RAF Merston. He continued to fight and increase his score to ace status but was shot down by flak over the sea and killed in November of 1941. He was 25 years old. In Jasper National Park, Alberta, 7,500-foot Mount Gaunce is named in his honour.

“Spud” Hayter was born in an entirely different world—in the port town of Timaru, South Island, New Zealand—in 1917. He took private flying lessons at Marlborough, and joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) in 1938 on a short service commission. While flying as an “observer” in a Vickers Vildebeest, he crashed on two occasions, but avoided major injury. With war looming, he sailed for England in July 1939, and was posted to 98 Squadron at RAF Hucknall, flying the Fairey Battle. In November, he crashed again after some low flying, but escaped injury for the third time. He was posted to 103 Squadron in France. During the Battle of France he was shot down on 16 June, attempting to land. Shortly thereafter, the squadron and the hapless Battles were withdrawn to England. He volunteered for Fighter Command, joining 605 County of Warwick Squadron (after a brief assignment to 615 Squadron) in September. By the end of the month, he had been shot down again—this time, descending from 25,000 feet by parachute, he landed on the grounds of an estate where a cocktail party was in progress—and was invited forthwith. After 605, he was rested as a flying instructor starting 1 May 1941. However, he was on board during two separate crash landings (by the same student pilot) and he was made operational again (finding no rest in instructing!) He joined 611 Squadron, continuing to increase his score, but crash-landing his damaged Spitfire yet again (his eighth crash). He was awarded his first DFC and was given command of 247 Squadron in North Africa. Following this he instructed Turkish pilots on the Hurricane then joined 74 Squadron in Iran and Egypt, then back to France, leading the “Tigers” against the Germans until the end of 1944. When Cuthbert Orde sketched his portrait in 1941, he said this of Hayter: “... tough, steady and a damn good type. He is one of the chaps who make me grin when I meet them.” He survived the war and eight crashes and died in 2006 in the small farming town of Takaka, New Zealand near the southern shores of Golden Bay.

Two men who fled the Nazi invasions of their homelands to fight with the RAF—Adjutant Émile François Marie Léonce Fayolle, DFC and Sergeant Karel Miroslav Kuttelwascher, DFC and Bar—both by Eric Kennington.

The Gallic and dramatic Fayolle was born in the middle of the First World War into a family with deep military roots. He joined the French Armée de l’Air in 1938 and was just finishing fighter school in Oran when the Germans invaded. He took an aircraft from his base and fled to Gibraltar, then took a ship to England and joined forces with the RAF. Having converted to Hurricanes, he was posted to a series of units—85, 145, 242, 611 and 340 Squadrons. In July 1942, he took command of 174 Squadron at RAF Warmwell. Shortly after taking command of 174, he was hit by anti-aircraft fire while supporting the Canadians during the Dieppe Raid (Operation JUBILEE). He is buried alongside the 907 Canadians killed that day.

Karel Kuttlewascher was born in Svätý Kríž in Czechoslovakia, just two weeks after Fayolle’s birth in 1916. He joined the Czech Air Force in 1934, qualifying as a pilot in early 1937. When the Nazis occupied his homeland, he escaped to Poland and then to the Baltic coast, where he took a ship to France. Being a foreigner, the only French unit he could join was the French Foreign Legion, so he journeyed to Algeria to become a Legionnaire. When France declared war on Germany with Great Britain, he was released and accepted into the Armée de l’Air. During the Battle of France, he claimed to have shot down 6 enemy aircraft. He escaped to Casablanca and from there to England where he joined the RAF and converted to Hurricanes. He joined No.1 Squadron at RAFWittering in October, but he did not claim an enemy aircraft until February 1941. He converted to night intruder Mosquitos with 23 Squadron at RAF Ford in 11 Group. He claimed 18 aircraft shot down by war’s end and was awarded the DFC twice. After the war he spent a year with the new Czech Air Force before joining British European Airways as an airline pilot. He died suddenly of a heart attack in 1959 at the age of 43.

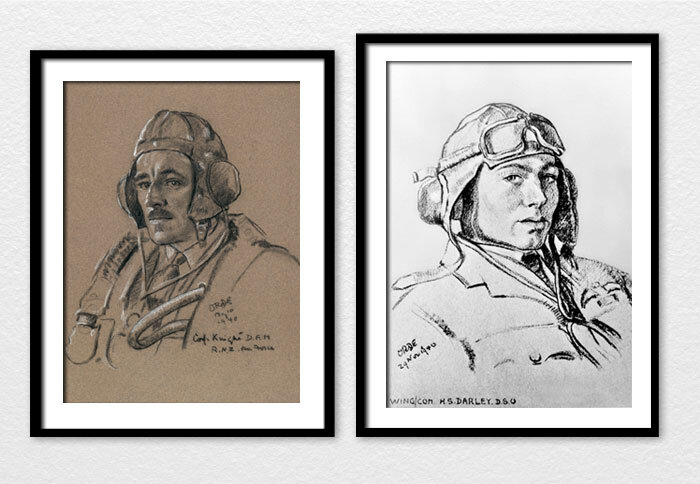

Earlier portraits by Cuthbert Orde showed men in flying gear—like Corporal (later Flight Lieutenant) Colin Beresford Graham Knight, DFM, (left) of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and Wing Commander (later Group Captain) Horace Stanley “George” Darley, DSO

Knight was born in 1912 in the tiny community of Tolaga Bay on New Zealand’s North Island. He was originally in the New Zealand Army, but transferred to the RNZAF in 1937 as a Wireless Operator/Gunner. He flew with 99 Squadron and was awarded his DFM for his effective and diligent radio work under fire during a very difficult operation in December of 1939 in which half of his attacking force of 12 was lost. He later served as Signals Leader, 40 Squadron RNZAF and was also attached to an RAF Transport unit working out of Montréal flying Liberators across the Atlantic. He survived the war, dying in 1998.

“George” Darley, born in November of 1913, was Commanding Officer of 609 Squadron in 1940 during the early stages of the Battle of Britain. He joined the RAF in 1932 and began his flying career in relatively little known and ungainly biplanes known as Fairey Gordons, Vickers Vincents and Fairey IIIBs. He flew these aircraft in Yemen and British Somaliland. He fought in the Battle of France and then with 609 Squadron at RAF Northolt in the Battle of Britain. In the three months that he commanded 609, the pilots scored 85 victories with the loss of just 7 of their own aircraft. Darley was awarded the DSO during this period, the first to be awarded for leadership in the Battle of Britain. During his 27-year career with the RAF, he commanded 11 RAF Stations and flew 65 different types. He died at the age of 86.

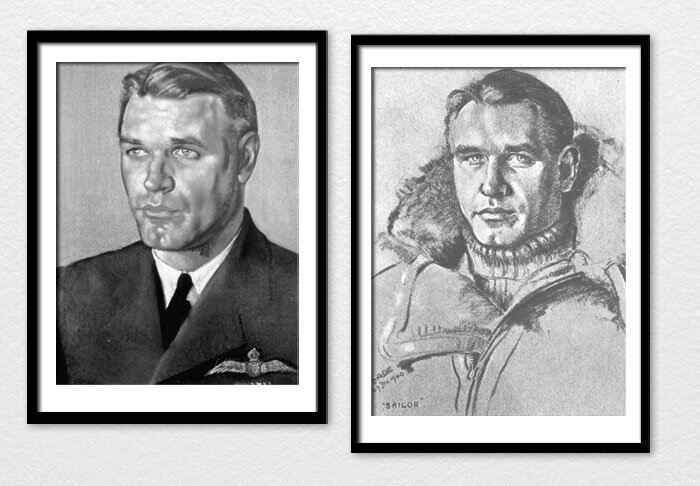

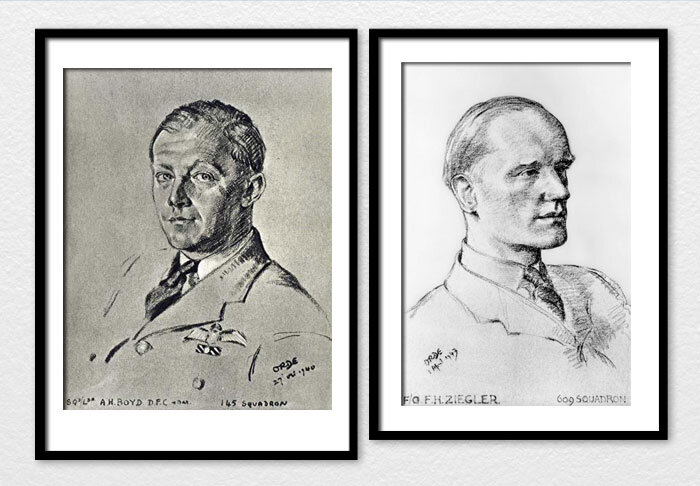

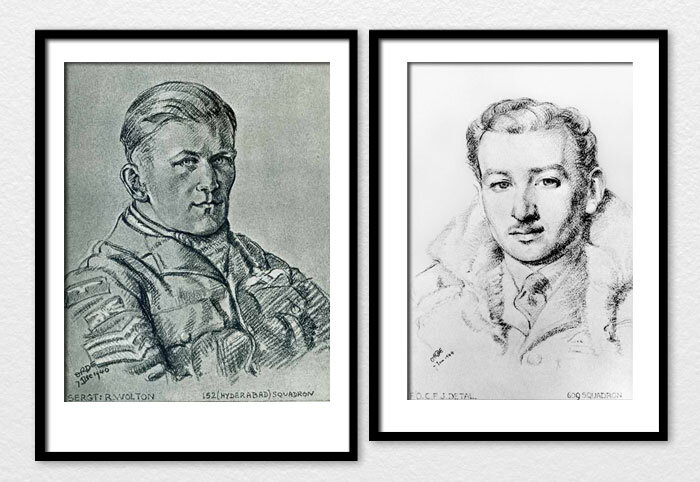

As far as fighter pilot legends of the RAF go, you don’t get much bigger than Group Captain Adolph Gysbert “Sailor” Malan, DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar. Both Kennington (left) and Orde completed portraits of Malan, both of which clearly display the man’s strength of character and charismatic good looks. Later in the war, Orde would complete a colour oil painting of Malan as well. Like Orde’s portrait of “Johnnie” Johnson, his rendition of Malan is captioned with a simple name—“Sailor”. Malan was born in South Africa in 1910. At the age of 14, he joined the South African Training Ship General Botha and then went on to a brief career as a merchant naval officer aboard the Lansdowne Castle. It was this foray into the marine world that earned him the nickname “Sailor” amongst his fighter pilot comrades. He joined the RAF in 1935 and completed his flying training by the end of 1936. His first squadron assignment was to 74 Squadron flying Gloster Gauntlets. He was still with 74 Squadron when they re-equipped with the formidable Supermarine Spitfire in February 1939. Malan and 74 Squadron saw action only 15 hours after Britain entered the war against Germany—but it was not the kind they wanted. They were scrambled to intercept what was thought to be incoming enemy aircraft. Instead they ran into the Hurricanes of 56 Squadron and shot two of them down during an incident that has become known as the Battle of Barking Creek. One of the 56 Squadron pilots, Pilot Officer Montague Hulton-Harrop was killed—the first RAF pilot to die in the war. The ensuing court martial pitted Malan against his own pilots. The two 74 Squadron pilots, including future ace John Freeborn, were acquitted, but much bad blood had been spilled in the process. Following the squadron’s covering of the British Army withdrawal at Dunkirk, Malan was awarded a DFC. In August of 1940, at the height of the Battle, Malan was given command of his 74 Squadron Spitfires and, on 11 August, he and his pilots shot down a total of 38 aircraft in four separate battles. Malan is quoted as saying “Thus ended a very successful morning of combat.” Malan would go on to command the Biggin Hill Wing, to be the station commander at Biggin Hill, to command the 19th Wing, 2nd Tactical Air Force, and finally to command 145 Free French Wing, taking them over the Normandy beaches on D-Day. He finished his fighter pilot career with 27 victories and with the rank of Group Captain. After the war, he resigned his commission and returned to South Africa, joining the Torch Commando, an anti-fascist and anti-apartheid group. He was the first president of the organization, dedicated, in his words, “to oppose the police state, abuse of state power, censorship, racism, the removal of the coloured vote and other oppressive manifestations of the creeping fascism of the National Party regime.” In one 75,000-strong rally in Johannesburg, Malan said “The strength of this gathering is evidence that the men and women who fought in the war for freedom still cherish what they fought for. We are determined not to be denied the fruits of that victory.” Malan died in 1963 at the age of 53 from Parkinson’s disease.