CROSSROADS OF COURAGE

As the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain is upon us, it is important to honour those of “The Few” that gave so much. There is an intersection of two roadways in the city of Calgary which endeavours to remind us every day of two Albertan Canadians who were among those who stopped the German advance on the north coast of France. Sadly, few are aware of it. Here is the story of Douglas Bader, William McKnight and Noel Barlow, three determined men.

The people of Calgary, as in every large and bustling city in North America, go about their daily lives in an insular fashion, largely oblivious of the people around them—a Starbucks “trenta” in hand, loaded down with personal gear, ear buds plugged in and listening to their choice of music, never looking up, thumbs flashing away on their “personal devices” or looking at their latest pouty-faced posts on social media. The world around them, the one that begins outside their personal space, is no longer engaged or seen or heard.

This phenomenon is not isolated to Calgary. It is a worldwide epidemic of self-focus, self-promotion and self-admiration. We have moved to a world where cyber addiction is the norm and people would rather interact with a small computer in their hands than look up and talk to the person across from them, or look out and see and hear and become part of a wider community. In fact, most people welcome the “personal device” as a way of tuning out the world around them.

There was a time, however, when men and women walked the streets of Calgary with their heads held up. It was a time when people in Calgary and the small towns across the Prairies understood that they were not alone, that they were part of a larger community of men and women. It was a time when what happened on the far side of the world did matter to the people in a small farming town out on the bald prairie. It was a time when young men, seeing the looming disaster on the horizon, understood the danger, and moved towards it. It was a time when individualism was praised if it was for the good of all. Today our focus is entirely on self, on making choices that will benefit ourselves, that will help us achieve our personal goals of money, love and business success—choices that will positively affect our resumés.

Every morning and evening, at a major intersection east of the city’s downtown core and just south of the airport, Calgarians in cars, buses, pickup trucks and commercial vehicles pile up at the traffic light. The cold winter weather or steaming summers keep every one of them cocooned inside their machines. Above them, suspended from aluminium poles, are two signs of white reflective vinyl on a green background. One says McKnight Boulevard, the other Barlow Trail.

On a downtown canyon-like street, twenty commuters await the arrival of the “C-Train”, a light rail service that carries people and their personal devices east and west and south. Texting and posting and watching “vids”, they briefly look up, but the name on the destination board on the front of the train barely registers—McKnight. To all of them it is the name of a light rail station, an off-ramp on Highway 2, a way to get to the airport, a street like any other. Not one thought is given to the origins of that name. And that’s a shame.

Calgary Transit System’s C-Train connects the east, south and west parts of the city and railcars bearing McKnight’s name roll through town on a tight and busy schedule. Business men and women use the light rail system every day, but I wonder how many, if any, think of the handsome, wild-spirited and tragic triple ace known as Willie, as they step on board.

In a world where urban development spreads like mould, outwards over farmland, enveloping small villages and towns, we are inundated with pretentious and saccharine street names that mean nothing except that those who chose them have little imagination and care only about marketing and little for history and memory. I just took a small sampling of suburban street names in one particularly egregious new neighbourhood in Ottawa: Shadow Ridge Drive, Evening Shadow Avenue, Blossom Trail Drive, Dawn Tara Drive, Rockrose Way, Willowmere Way, Gracewood Crescent, Bufflehead Way, Meadowlily Drive, Flat Sledge Crescent, Mocha Private, Purple Finch Crescent, Antique Court and on and on. It makes me laugh... and cry.

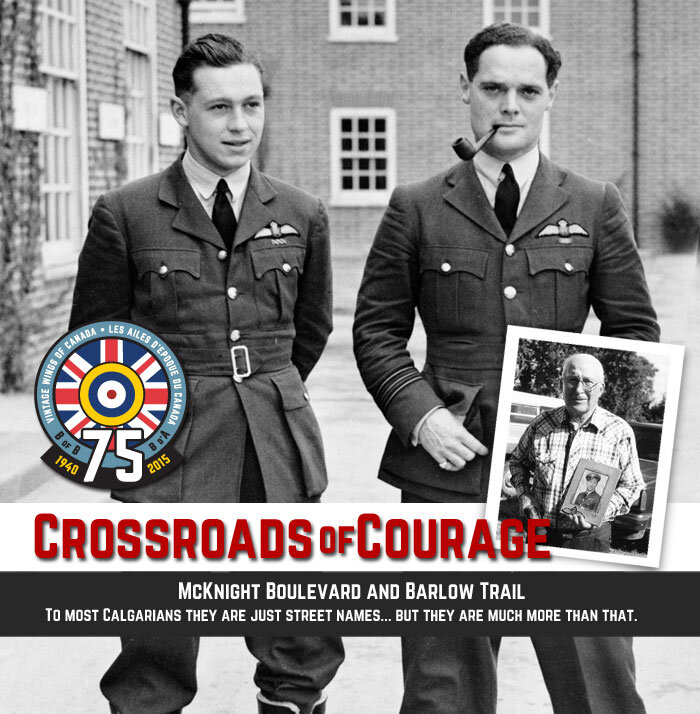

Seventy five years ago this year, the namesake of McKnight Boulevard, a young Calgarian by the name of William Lidstone McKnight, was battling for the fate of Europe in the skies over England and France. He often flew with his squadron commander, a legendary fighter pilot by the name of Douglas Bader, a man who had no legs. Each and every night, these two fighter pilots rested, caroused, attempted to sleep and readied for the next day’s inevitable pitched battles, while the ground crews of No. 242 Canadian Squadron laboured through the days and nights to refuel, repair and rearm their Hawker Hurricanes. Bader’s loyal, diligent and talented “engine fitter” [mechanic] was another Albertan by the name of Noel Barlow. McKnight and Barlow—one died, one lived, and Bader, an Englishman, had a lot to do with their names being associated with two intersecting thoroughfares in the booming oil town of Calgary.

Group Captain Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader, CBE, DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar

The story of Douglas Bader is familiar to many in the world of aviation. The fighter pilot, who lost his legs in a flying accident, overcame his disability at a time when handicapped people were marginalized and went on to be a top ace, a thorn in the side of the German prisoner of war system and a living legend (in books and film) after the war. But as large a man as he was in life, Bader was exceptionally loyal to the men he led into battle and he was instrumental in creating a permanent way to remember two of his men from the Battle of Britain—Willie McKnight and Noel Barlow. Unfortunately, few are aware of it.

(From the Royal Air Force Museum website)

“Douglas Bader was born in St John’s Wood, London on 21st February 1910 and spent the early years of his life in India before returning to the United Kingdom. His uncle was adjutant to the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell and, at the age of 11, Bader decided that he would join the RAF.

Seven years later, he won a scholarship to Cranwell, graduating in 1930. He was a keen sportsman, representing the College at Rugby, Shooting, Hockey, Athletics, Boxing and Cricket—the College Journal reported a boxing match in which “Bader in his usual ‘no-time-to-spare’ manner went straight at his opponent and knocked him out with two very hard rights. He took about the same time as he did last year, and is a very dangerous man to meet.”

From Cranwell Bader was posted to No. 23 Squadron at Kenley, flying the Gloster Gamecock. He developed a talent for aerobatics and in 1931 performed in the RAF Display at Hendon.

On 14 December, shortly after the Squadron’s Gamecocks had been replaced by Bristol Bulldogs, Bader crashed at Woodley aerodrome, near Reading and was seriously injured. His right leg was amputated that day, and the left a few days later.

Related Stories

Click on image

Within six months of the accident Bader had not only learned to walk unaided on artificial legs, but was determined to fly again. Although he was able to demonstrate that he could meet the RAF’s demanding requirements, a medical board ruled that he could not continue as an RAF pilot. He left the RAF in 1933 and joined the aviation department of the Asiatic Petroleum Company, soon to become part of Shell.

For such a keen sportsman the loss of his legs was a terrible blow, but he responded by taking up golf and rapidly achieved a very high standard. He sustained his love for the game throughout his life.

In the summer of 1939 Bader, aware that war was inevitable, set out to rejoin the RAF. He easily passed tests at the Central Flying School and then undertook a refresher course before joining No. 19 Squadron in February 1940 at Duxford. Here he first flew the Supermarine Spitfire, undertaking convoy patrols but without seeing action. A posting to No. 222 Squadron, also at Duxford, brought action over Dunkirk in June 1940 and on the 24th he was promoted to squadron leader and given command of No. 242 [Canadian] Squadron at Coltishall.

The squadron had suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of France and morale was low. Bader immediately transformed his unit, concentrating on improving his pilots’ flying, teamwork and confidence. The Squadron’s first major success came on 30 August when they claimed 12 enemy aircraft, of which Bader shot down two. As the Battle of Britain progressed Bader led larger formations, with 242 and other squadrons forming the Duxford Wing. By the end of 1940 Bader’s squadron had shot down 67 enemy aircraft, for the loss of only five pilots killed in action.

In March 1941 Bader left 242 and was promoted to lead the fighter wing based at Tangmere. The RAF now mounted daylight raids on occupied Europe, with bombers escorted by large numbers of fighters, to draw German fighters up to be attacked. Bader’s score rose to 20 confirmed as destroyed (plus two shared) but on 8 August he was forced to bail out of his Spitfire. He recorded in his logbook “Shot down 1 Me 109F & collided with another. POW” but opinions vary, and a more recent investigation suggests that he may have been the victim of friendly fire.”

Bader was a champion for his men, long after the war. In his biography, Reach for the Sky, Bader spoke about his work to have a street in Calgary named after his wingman McKnight:

“The whole of 242 Squadron’s successes in this phase could be epitomized by the young Canadian from Calgary, Willie McKnight. He shot down a Me109 [sic] over Dunkirk on that very first day, followed by a couple more plus a Dornier 17 on 29 May. Two days later, he got two Me 110s. He brought his personal score to something like sixteen and half by the end of the Battle of Britain. Then in January 1941, he flew on one of the original low-level intruder missions aimed at Germans in France. Six Me 109s attacked McKnight and he was killed.

Some years after the war I visited Calgary which was the hometown of William McKnight. In a speech at a Chamber of Commerce lunch, I suggested to the mayor and some of the senior citizens that they should name some of their streets—and indeed the new Calgary Airport then being built—after some of the Canadian pilots of World War II. I visited Calgary many times in the 1950s and 60s and there is now a new road leading to the airport which is called McKnight Boulevard. Later I unveiled a commemorative plaque to Willie McKnight in the passenger hall of the Calgary Airport. A fine tribute to a Canadian who died at the age of twenty-one [sic].” From Reach for the Sky, by Douglas Bader

Bader was subsequently successful in convincing the city fathers to name a street after his young wingman. In October of 1969, a roadway leading to the Calgary Airport became McKnight Boulevard, and as aviation historian Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail so eloquently put it, “The Canadian ace with no known grave now had a living memorial.” From Words on the Street, Homes and Living Calgary, April/May 2013

Bader was also instrumental in having another street in Calgary named for his old friend and devoted aircraft fitter from the Battle of Britain—Corporal Noel Holland Barlow. When Bader first visited Calgary in 1955, he was met at the airport by Barlow. It was reported in the Lethbridge, Alberta Herald newspaper:

“Legless Ace Arrives for Calgary Visit CALGARY (CP) A tired but smiling Douglas Bader, legless war ace, stepped off a TCA airliner at Calgary to be greeted by a swarm of admirers. Sniffing the balmy evening air, he exclaimed: “This is for me. Who wouldn’t love weather like this.” He had come from the deep-freeze of eastern Canada for his first visit to Calgary. The man who led the famed 242 RAF squadron was greeted by officials of Shell Oil Co. Ltd., the company which he represents in London as an aviation expert. He also had a happy reunion at the airport with two former pilots of his RAF Canadian squadron, Noel Barlow, a native Calgarian, and Fred Bentley, who came to Western Canada at the end of the war. “This is the happiest moment of my trip,” he told them. He will leave for Vancouver on Tuesday.”

Squadron Leader Douglas Bader sits on the canopy rail of his 242 Squadron Hawker Hurricane LE-D. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Group Captain Douglas Bader heaves an artificial leg into the cockpit of a Supermarine Spitfire. This was after the end of the Second World War, as Bader was promoted to that rank in 1946. Photo: RAF

Flying Officer William Lidstone McKnight, DFC and Bar

William “Willie” McKnight was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1918, one week after the end of the First World War. He moved with his family to Calgary soon after. Willie was rambunctious, rebellious and brilliant. In high school he excelled in academics, athletics and getting into trouble, once crashing his father’s car into a neighbour’s fence while trying to impress a girl. His marks were good enough to get him into the University of Alberta’s medical program in 1938, but his wild ways and cockiness brought him perilously close to expulsion. His romance with his girlfriend Marian was in tatters, and like a young man signing on with the French Foreign Legion to put his past behind him, he joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) and headed to England and pilot training.

In mid-April of 1939, McKnight received a short service commission as an acting Pilot Officer and earned his RAF pilot’s brevet at No. 6 Service Flying Training School at RAF Little Rissington, Cheltenham. His permanent Pilot Officer commission would come into effect one year later. Willie’s wild Albertan heart got him into trouble on several occasions. He was under arrest and confined to barracks on two occasions, one of which was for “perpetrating a riot”. One can only guess at what that might have meant. But early on, his instructors saw his potential and, despite his shenanigans, he graduated as a pilot. Willie’s personality was a balanced dichotomy. While he was rebellious, he was decidedly loyal. While he ran away from emotional distress in Canada, he ran towards danger and operational stress in battle. While he appeared shy and reticent, he was a fierce warrior and a leader... both in the air and in the public house.

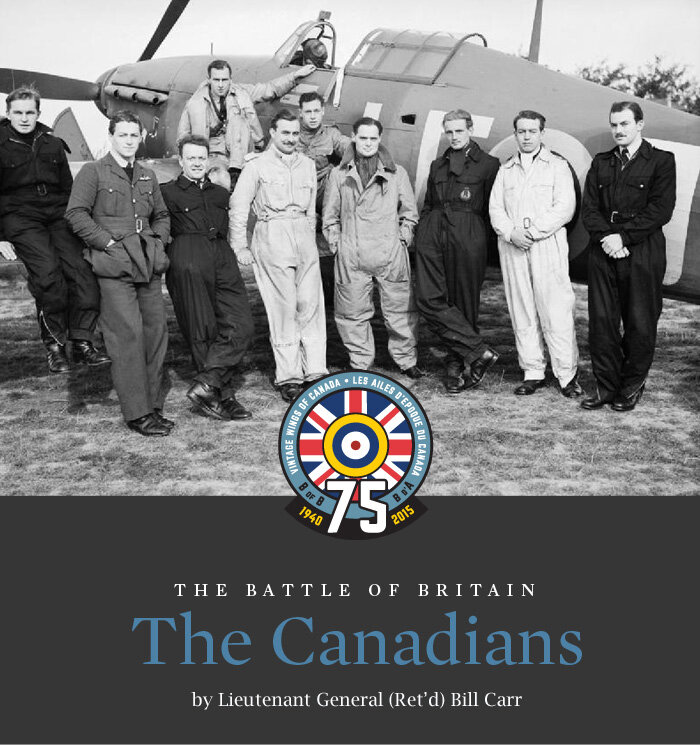

McKnight was posted to 242 Squadron in November 1939 at a time when the squadron began training up with obsolete Fairey Battles and twin-engine Bristol Blenheims. 242 “Canadian” Squadron, a former Royal Air Force seaplane anti-submarine patrol squadron at the end of the First World War, was reformed in late October of 1939, shortly after the start of the Second World War. The squadron was chosen to become the RAF’s “Canadian” unit, manned entirely by Canadians, most of whom were already serving in the RAF. The idea behind the formation of an all-Canadian squadron was to give the Canadian home front a boost and show the average Canuck that their countrymen were well and truly engaged in the war. As a public relations idea it was very successful and Canadians back home began to follow their exploits.

As the Battle of France developed in May 1940, 242 Squadron, now a Hurricane unit, sent a small detachment of pilots, including McKnight, to fly with other British Expeditionary Force squadrons. McKnight was attached first to 607 County of Durham Squadron and then to 615 County of Surrey Squadron. Within days of his arrival in France, young McKnight scored the first of his 17 confirmed victories over Luftwaffe pilots on 19 May. Things were happening exceedingly fast in France at this time, and just two days later McKnight and his fellow 242 pilots in France were recalled to England. By 26 May, Willie had re-joined 242 Squadron now at RAF Biggin Hill. They flew each day from Biggin Hill to RAF Manston and then to France, where they flew operations to thwart the German attempts to destroy the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk.

During the days of the Dunkirk withdrawal, Operation Dynamo, McKnight claimed six more enemy aircraft and by 7 June, had become a double ace with 10 victories. His prowess in the air and his courage in the face of the enemy had already brought him notice, and in early June he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), being gazetted on 14 June. The citation accompanying his DFC read:

“One day in May, this officer destroyed a Messerschmitt 109 and on the following day, whilst on patrol with his squadron, he shot down three more enemy aircraft. The destruction of the last one of the three aircraft occasioned a long chase over enemy territory. On his return flight he used his remaining ammunition, and caused many casualties, in a low flying attack on a railway along which the enemy were bringing up heavy guns. Pilot Officer McKnight has shown exceptional skill and courage as a fighter pilot.” – from Hugh Halliday’s excellent book No. 242 Squadron – The Canadian Years, the Story of the RAF’s “all-Canadian” Fighter Squadron

Expecting to be rested then, instead 242 Squadron—this time in its entirety, including ground crew—was returned to France on 8 June to cover that portion of the British Expeditionary Force still operating in France south of the Seine River. By this point, the situation in France was one of desperation and 242 Squadron was charged then with covering the lesser-known evacuations, Operations Cycle and Ariel. There was a rapid series of relocations due to the changing battlefront—three times in one six-day period! Soon separated from their ground crews, the 242 Squadron pilots had to refuel, rearm and service their own aircraft. In addition to flying and fleeing, Willie is reputed to have commandeered a luxury automobile and carried on an amorous affair with a young woman from Paris. Later, the story goes, he would attempt to secret the same lovely Parisienne to England aboard a transport aircraft.

Hawker Hurricanes of 242 Squadron rise above the clouds during the Battle of Britain. Photo: Imperial War Museum

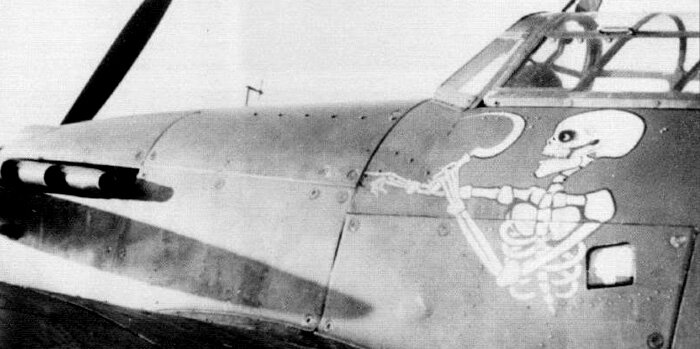

McKnight’s brashness, dark humour and medical background found artistic outlet in his idea for “fuselage art” on LE-A. The laughing skeleton Grim Reaper pointed towards the enemy who was about to be scythed down by the young knight of the air. The artwork appeared on both sides of the Hurricane. Photo: RAF

The last of 242 Squadron’s pilots flew back to England on 18 June. The never-ending sorties and the exhausting pace had taken its toll on the young Calgarian and he was hospitalized in early July for exhaustion, weight loss and stress-related illnesses. The squadron too had suffered while in France with 11 pilots killed, wounded or captured, and as they regrouped in England, they were confronted with a new squadron commander—acting Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, who brought a new style of leadership, one which at first ruffled feathers, but soon had the entire squadron supporting the bold and charismatic leader. Bader recognized talent when he saw it and he regularly flew with McKnight as his wingman. With a man like McKnight protecting his flank, Bader’s score increased as well. McKnight, Bader and the pilots of 242 Squadron fought tenaciously throughout to next three months and McKnight rapidly accumulated victories, becoming a triple ace by the end of the Battle of Britain.

McKnight wrote to a friend back home during the Battle of Britain, and in his letter reveals a fatalistic philosophy:

“August 26, 1940

Dear Mike. This game is damn good fun when you are fighting bombers as they’re just like picking apples off a tree but fighters are a hell of a different proposition and keep you moving like greased lightning. It’s a funny thing this fighting in the air. Before you actually start or see any of the Hun you’re as nervous and scared as hell but as soon as everything starts you’re too busy to be afraid or worried.

We’ve been up against raids of 300 to 60 or 150–200 to 12 but either we’ve killed all their real good pilots and they’re using new young ones or else they are losing their nerve. They ain’t got the same guts they used to have and except in a few cases try to avoid a real scrap. We’ve only got five of the original twenty-two pilots in the squadron left now and those of us who are left ain’t quite the same blokes as before. It’s peculiar but war seems to make you older and quieter and changes your views a lot in life.

I got over the 700 hour mark just a few days ago and I am still being offered a chance to return home as an instructor but the old reasons still keep me here and I suppose I shall remain here until the end or until the other end. I’ve got so used to the thrill and the, I don’t know how to express it, final feeling of victory that I’d feel lost and bored by a quiet life again.

Well, I really must go before I get sentimental or homesick. Write me soon and until then. Your friend, Bill” via AcesofWW2.com

In October, McKnight was written up in the London Gazette once again, this time for his second DFC or “bar”. The citation with this DFC reads:

“This officer has destroyed six enemy aircraft during the last thirteen weeks. He has proved himself to be a most efficient section leader, and has consistently given proof that he is a courageous and tenacious fighter,” – from No. 242 Squadron – The Canadian Years, the Story of the RAF’s “all-Canadian” Fighter Squadron by Hugh Halliday

After the Battles of France and Britain, targets became scarcer, and by January, the pace at which McKnight shot down enemy aircraft had slowed down—17 enemy aircraft shot down, two shared and three unconfirmed. He was promoted to Flying Officer and was celebrated in England and in Canada, particularly in Calgary, where people were proud of their native son. With meteoric combat careers like Willie McKnight’s however, the numbers game eventually catches up. On 12 January 1941, McKnight and M.K. Brown had just made attacks on a German “E” boat [a fast torpedo boat] and troop concentrations just inland from Gravelines, Holland, when a Messerschmitt Bf-109 was spotted by Brown. After making a hard turn to the right, he looked again for the 109 and McKnight. Neither could be seen—McKnight had vanished in an instant. He was 22 years old.

Later that day, the squadron lost another Canadian ace—Flying Officer John Latta of Victoria, British Columbia. Hugh Halliday, in 242 Squadron – The Canadian Years wrote:

“Flying Officer “Willie” McKnight, piloting P2961, did not return. He was dead, a victim either of flak or of the Bf-109. An original member of No. 242 Squadron, he had been its most outstanding Canadian pilot, shooting down at least sixteen (possibly eighteen) enemy aircraft and twice winning the Distinguished Flying Cross. His loss threw a pall of gloom over No. 242; it was front-page banner headline news in Calgary two days later... ...The Squadron had taken similar losses before. Nevertheless, January 12th, 1941 was one of the blackest days of its history.”

Today RAF Duxford is home to the Imperial War Museum, some of the finest warbird restorers on the planet and one of the greatest air shows in the warbird world—Duxford’s Flying Legends. During the Second World War and the Battle of Britain, it was the home to the Royal Air Force’s 242 Canadian Squadron and real flying legends like the three pilots shown here: (left to right) Willie McKnight, Douglas Bader and Eric Ball. All three are decked out in full dress and two are sporting the very same flight boots which kick Hitler’s behind on the noses of their Hurricanes. Bader, of course, did not need heavy flight boots as he had no legs and his artificial legs sported shoes. All three are wearing ribbons—McKnight and Ball the DFC and Bader the Distinguished Service Order. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The death of the rebellious and wild-hearted Willie McKnight was a terrible blow to the squadron and to the home front, but he has been remembered well over the seven and a half decades since that day near Gravelines. Though he has no known grave, his name lives on in Canadian air force history as one of the great natural fighter pilots of all time. Vintage Wings of Canada is restoring a Canadian-built Hawker Hurricane XII, which will one day in the near future bear the markings of 242 Squadron Hurricane LE-A with McKnight’s skeletal and laughing Grim Reaper pointing forward to an enemy that has long ago become an ally.

In Calgary, people come and go on McKnight Boulevard. Thousands upon thousands of cars stream along its split roadways each and every day. At every intersection there is a sign that says “McKnight Boulevard”. In a thousand cars a day, a robotic female voice on a GPS calls out “Turn left on McKnight Boulevard in 100 metres”, yet I doubt a single person thinks of the handsome young man who gave his life in battle 75 years ago.

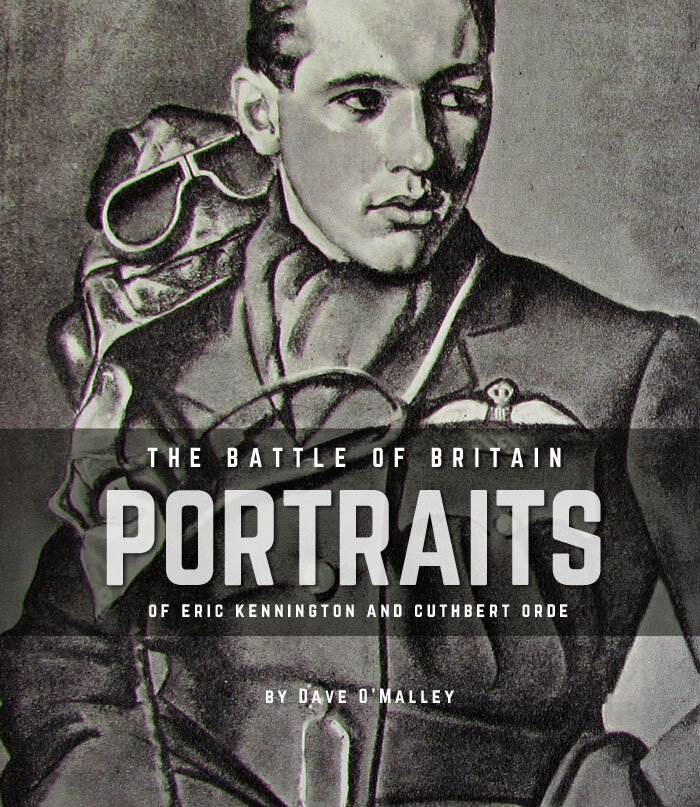

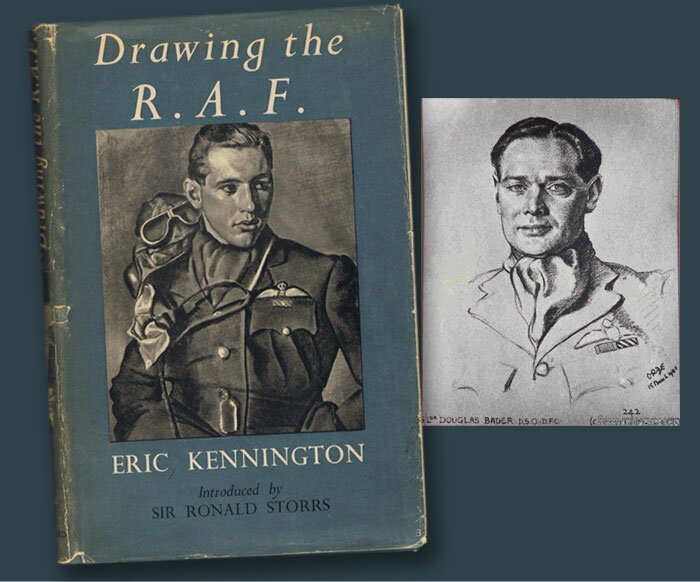

Two of the greatest portrait artists of the Second World War were Eric Henri Kennington (an infantryman in the First World War) and Cuthbert Julian Orde (a Royal Flying Corps observer in the First World War). Kennington drew both Bader and McKnight, but he chose to put McKnight’s portrait on his 1942 book, Drawing the R.A.F. (left). Cuthbert Orde published a portrait of Squadron Leader Douglas Bader (right) in his portrait compendium Pilots of Fighter Command - 64 Portraits by Cuthbert Orde – an album of portraits of Battle of Britain pilots. Images: Wikipedia

Flying Officer Noel Holland Barlow, RAF and RCAF

Noel Barlow was born in Denbeigh, Wales in December of 1912. His father was killed in the First World War and his mother remarried after the war. The family, including his brother Eric, emigrated from Wales to Canada, eventually, in 1932, owning and operating a farm near the small town of Carseland, about 30 kilometres southeast of Calgary. Like many young men and women in the interwar years, he became enamoured of aviation. Working hard in the mining industry (he worked at the Bear Lake and Giant Yellowknife Mines) and saving diligently, he finally accumulated enough money to pay for flying training at the Calgary Flying Club, earning his Canadian Private Pilot Certificate (No. 2225) in 1937 and then at the end of the year, his Limited Commercial Pilot’s Certificate (No. C-1464).

More than anything, Barlow wanted to fly fighter aircraft with the Royal Air Force which was recruiting in the Colonies, but first he would have to save again, this time for a one-way ocean liner ticket to England. Once he got to an RAF recruitment office in Great Britain, he was devastated to learn that, at the age of 26, he was considered too old for military pilot training despite already having a license. Now he was well and truly between a rock and a hard place, as he was 6,000 miles from the family farm without money to live on. Faced with a grim short-term future, he “had no choice but to join the RAF as ground crew”.

Both Noel Barlow and Willie McKnight made their way to Liverpool, England aboard the same ship – Canadian Pacific Steamships' CPS Montclare. McKnight sailed in January of 1939, while Barlow did so in December of 1937.

So, if he was to be ground crew (an “erk” or engine “fitter” in the parlance of the RAF at that time), he was going to be the best he could be. As the war approached, he knew his services would be very important and he strove to become an expert on the subject of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. Shortly after the start of the Second World War, he learned that the RAF was looking for Canadians to join the newly formed 242 “Canadian” Squadron—both pilots and ground crew. He signed up and was accepted immediately. During the Battle of France, he was part of the ground crew team that went to support the 242 Squadron pilots operating from the area south of the Seine River, and as such he was forced to move twice ahead of the rapid German advance.

Barlow and other 242 erks in France were eventually evacuated to England to rejoin the squadron under the new leadership of then acting Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, the charismatic, capable and legless fighter pilot of legend. Bader was an inspirational commander, always leading from the front, always in the fray with his men. His fighter pilots loved him and his ground crews were devoted to him. He chose Noel Barlow as his personal fitter, responsible for, among many things, the condition of Bader’s personal Hawker Hurricane—LE-D (during the Battle of Britain, Bader was known to have three personal machines: P3061, an unknown serial and V7467, all coded LE-D). Throughout the Battle of Britain, Barlow worked tirelessly to keep the squadron operational and to service Bader’s machine. A strong and lifelong bond was built between the two airmen, based on mutual respect, the highest levels of performance and their shared experience. After the Battle of Britain, Bader and Barlow remained connected as 242 Squadron flew operations across the English Channel. Bader’s superb leadership skills and ability to inspire his men led naturally to a promotion to a Wing Commander at RAF Tangmere with 145, 610 and 616 squadrons making up his wing.

Shortly after Barlow had joined the RAF, the age limit for pilot trainees had been increased, but he stayed with 242 as a fitter until Bader’s departure to lead the new wing. After eighteen months, despite a promised promotion to sergeant, Barlow then requested a transfer to pilot training, something that was supported in by Bader himself. His request was granted and he soon found himself a lowly Leading Aircraftman crossing the Atlantic Ocean, bound for the all-through No. 3 British Flying Training School in Miami, Oklahoma. The British, with the co-operation of the American government and private enterprise, had set up six flight training schools for RAF student pilots, two of which were in Oklahoma. While Barlow was in Oklahoma, Bader was shot down on 9 August 1941 and taken prisoner, and his old fitter was moved to write a tribute entitled “MY IDEAL” for a No. 3 BFTS publication:

“Having in the past been a member of one of Britain’s most famous fighter squadrons for a period of eighteen months as a fitter, it is with pride and a feeling of honour that I have accepted a request to write a few words of praise in honour of my late Commanding officer Wing Commander Bader, D.S.O, D.F.C. and Bar, the famous legless pilot. Firstly, I would like to impress upon all who read these few lines that he is, shall I say, my hero for, though a child may have a hero, the same, I think, could easily apply to a grown man. During the dark days of the fall of France and the heroic episode of Dunkirk, our squadron, then led by a Canadian C.O. [Squadron Leader Fowler Gobeil], fought in France before and after Dunkirk and upon arrival back in England, we were sent to a quiet spot to patch up scars received in France. To the disappointment of all, especially to the many Canadians on the squadron, the C.O. was transferred back to Canada on urgent business. So, for a short while we as a squadron felt we were forgotten by Air Ministry. However, we ground men had plenty to do – new wings to change, guns to refit, engines to test, etc., – preparing for the famous Battle of Britain.

Then one day a rumour started that the new C.O. was coming, but he didn’t seem to be the type of man for whom we had hoped. At least, that is what most of us were thinking when we heard that he had no legs. It was one morning when I had just finished checking a thirty-hour inspection that a low built car pulled up almost in front of the machine from which I was climbing down. The car engine was shut off and a Squadron Leader stepped out. Being an “erk”, I became curious and found an excuse to pass near to the car with the result that I was asked to show the Squadron Leader to the Engineer’s office, which I did. I noticed that he had a peculiar walk, but he did not look to me like a man with his legs missing.

And so into the life of our squadron and into everyone of us came an admiration for a great leader of men. Throughout the trying but triumphant days to follow, everybody did their utmost to please him, whether they be a pilot, grease monkey, or whatnot, and he inspired us on with his grim determination to shatter all Jerries that came his way.

Almost overnight our squadron changed from a carefree attitude to one of grim earnestness. Our victories mounted each day, and our leader was always in front leading the squadron into great odds, but the bigger the odds the better the C.O. liked it, and it was that what made us all worship him. Let me add that, to keep up with his boundless energy, our work had to be carried out on day and night, but we did not mind as the results and effort we worked for were always fulfilled two-fold. With our C.O. work came first, then, if time could be found, sports and amusement for all, and his system worked very successfully on our squadron. It was in recognition of his fine work with 242 Squadron that he received the D.F.C. and D.S.O.

But a dark cloud descended upon us one day. It was learned that our C.O. was to leave us as our Wing Commander, so out of our everyday life stepped a man we all worshipped. He was kind to all, brave, dauntless, and full of never ending energy which always left us in awe. His spirit still prevails amongst his followers of the past and, although he is in the hands of the enemy, let us, as perhaps future leaders of tomorrow, try to carry on what he has left us to finish with that same spirit that Jerry cannot understand and will never break.”

The Miami, OK school was run by the Spartan School of Aeronautics. Despite the civilian school, discipline was decidedly RAF. Barlow made it through his training successfully and along with his classmates attended his wings parade. But all did not go well. Noel Barlow explained what happened to Nose Art Historian Clarence Simonsen in an interview for a piece Simonsen did on the 242 Squadron emblem:

“Noel explained how he was 30 years old, when he arrived at Miami, Oklahoma, which was at the least ten years older that the other trainees. He was the old man, had seen eighteen months of war, up close, from the very beginning in France, then Battle of Britain, and he had been flying planes since 1936. Noel was a veteran, a bit cocky, and during training took a dislike to one British Flying Instructor. "He was not a good pilot and damaged two aircraft on landing accidents, but he thought he knew it all." "He also treated me like a new cadet, which I didn’t like."

Noel further explained - "We operated under the Arnold Scheme, half Americans and half RAF cadets. The Americans had a Major in charge and the RAF had a Wing Commander named Roxbourgh. We wore American uniforms with only the RAF cap with a white stripe which stood for cadet." During the last few weeks of my training, the British Flying Instructor [who I hated] was being sent back to England, and they were holding a going away party for him in the Officers Mess. A number of us cadets had been drinking at the mess that night, upon return to our quarters we passed the Officers Mess. Due to a dare and too much to drink, I entered the Officers Mess and challenged the Flying Instructor outside to a fight. W/C Roxbourgh stepped between us and I gave him a slap on the back and presented him with a half bottle of whiskey, I carried under my coat. I then left, nothing was said to me until the end of our course. When we formed up for our class "Wings Parade", my name was called out and I was marched to the side of the complete class, where I remained until each classmate received his wings. Of course I did not receive my wings [second time] and was informed my RAF career was over. I was discharged and returned to Alberta, totally upset with what I had done, but I was a pilot, and still wanted to fly." via Clarence Simonsen

Barlow, inspired by Bader and McKnight and 18 months of hard work with 242 Squadron, was not one to quit, despite his setbacks. He journeyed back to his home in Alberta, enlisted in the RCAF, was accepted for pilot training, and finished his Service Flying Training at No. 15 Claresholm, Alberta. It was ironic in the extreme that he had travelled 7,000 kilometres to England to become a pilot, followed by another 4,500 kilometres to Oklahoma and then, finally, qualified as a winged pilot at Claresholm... just 100 kilometres from his home at Carseland, Alberta!

Following his Wings Parade, Barlow was assigned to No. 5 Operational Training Unit at Boundary Bay in British Columbia. Here, along with aircrew of every stripe (pilots, bomb aimers, navigators, gunners, engineers and radio men) he took training on the B-25 Mitchell and the B-24 Liberator.

A No. 5 OTU B-25 Mitchell in the skies over the Vancouver area. The photograph was taken by Noel Barlow during his training there. Photo by Noel Barlow, DezMazes Collection, via No. 5 OTU Facebook page

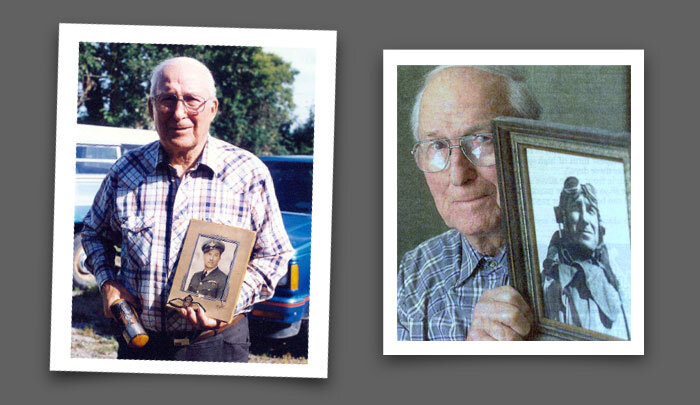

Two photographs of a retired and aging Noel Barlow. At right he holds a photograph likely taken during his flight training days at No. 3 British Flying Training School in Oklahoma. At left, he holds another photograph of himself as an officer pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Photos via Clarence Simonsen

For the rest of his life, Barlow would remain close friends with Douglas Bader, and on Bader’s frequent trips to Calgary, he and his wife always stayed with Barlow and his wife Jeanne in the small farming town of Carseland. The story goes that when Bader was visiting Calgary on one occasion, the city leaders wanted to name a street in his honour, but Bader declined, suggesting that such an honour go to his Alberta-born fitter, a simple and unknown man named Noel Holland Barlow.

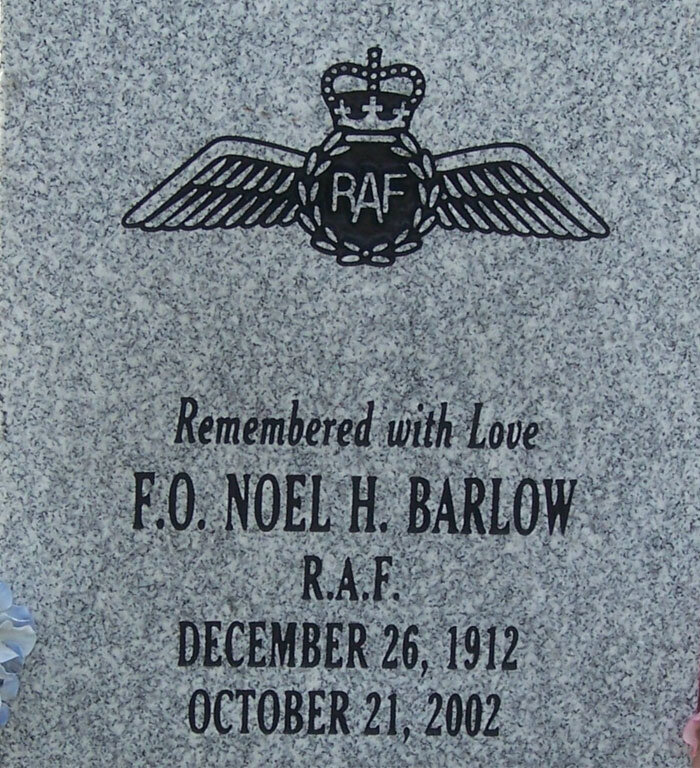

Barlow died in 2002 at the age of 90, exactly 20 years after his friend Bader. It is interesting to note that Barlow’s headstone features an engraved set of RAF wings even though he was thwarted twice by the Royal Air Force. It was the RCAF that awarded him his wings and commissioned him as a Flying Officer, but it is a powerful testament to his days with 242 Squadron and his love for Bader, that he chose to be remembered as a Royal Air Force airman.

There is no doubt that, in a rental car being returned to the Calgary airport today, the GPS shows an intersection ahead and that robotic voice intones “Continue on Barlow Trail for 300 metres, Prepare to turn right onto McKnight Boulevard North East” and in that moment, whether the tourist knows it or not, two great Canadian heroes are remembered.

Barlow’s headstone at the Strathmore Cemetery in Alberta shows that, despite the fact that the RCAF made him a pilot and an officer, his true allegiance was to his squadron mates in 242 Canadian Squadron and to his beloved leader Douglas Bader. Photo by Ancaster at FindaGrave.com

A highway sign in Calgary, Alberta bears the name of a simple corporal fitter in the Royal Air Force, a tribute to history, loyalty, determination and friendship.

The writer would like to thank Tim Dubé, Hugh Halliday, Clarence Simonsen, Todd Lemieux, Karl Kjarsgaard, Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail and Richard DeBoer for their assistance or research. If you want to do more to remember the likes of McKnight and Bader, we strongly encourage you to join the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, a worthy group that has done much for our aviation heritage over the past 50 years.